Economic growth acceleration: Potentials and policy imperatives

Economic growth, usually measured by growth of gross domestic product (GDP), remains a dominant development objective. It is recognised that development is a multi-dimensional concept. It encompasses many other elements such as equitable distribution of the fruits of economic growth, elimination of poverty, maintenance of reasonable price stability, participation of all sections of the society in the growth process, and improvements in indicators of human development, particularly health and education. Nevertheless, policy makers and analysts attach a great deal of importance to the acceleration of GDP growth. In part, the underlying rationale is that growth usually exerts a positive impact on several other elements of development mentioned above. In this backdrop, the objectives of this article are to: (a) present a brief review of GDP growth of Bangladesh; (b) identify the factors which underlie the observed progress; and (c) suggest policy actions needed to strengthen the causative factors.

GROWTH PERFORMANCE

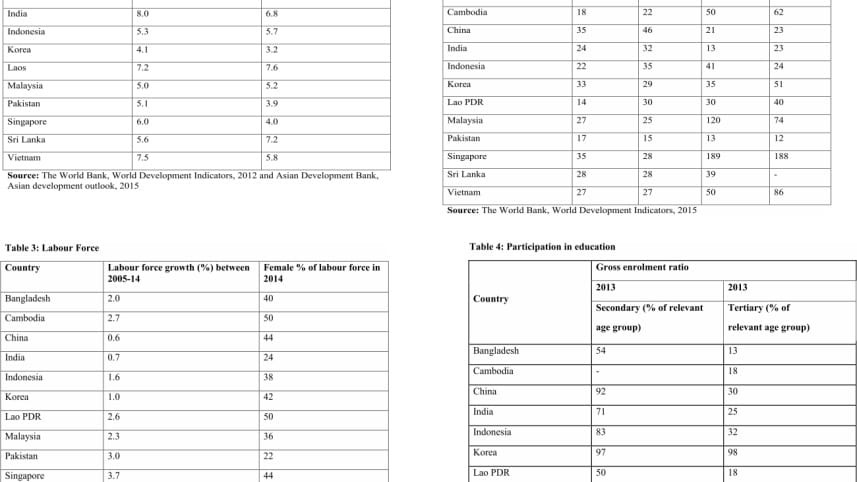

A country's growth performance can be evaluated in various ways. One way is to look at the change over time. Another is to examine how its performance compares with other countries, particularly neighbouring countries. Bangladesh has improved its performance in both of these criteria. The country's GDP growth averaged a mere 3.8% during 1980-1985; rose to 5.9% during 2000-2010; and to 6.2 percent during 2011-2015 (Table 1). The country also improved its ranking slightly among the 12 countries listed in Table 1. During 2000-2010, six countries recorded higher growth than Bangladesh, whereas during 2011-2015, five recorded higher growth.

The implication is that Bangladesh has the potential of accelerating its growth rate further so as to reach the rates achieved by countries such as Cambodia, Laos, China, India, and Sri Lanka with growth rates of about or above 7%.

Factors underlying growth and related policy imperatives:

INVESTMENT

There is widespread consensus that investment is a key determinant of growth. This is illustrated by the experience of Bangladesh as well. The acceleration of growth noted earlier was accompanied by a rising share of investment in GDP. The share increased from 15% in 1985 to 29% in 2014. Among the countries with higher rates of growth, China, India and Laos had higher investment to GDP ratio. On the other hand, Cambodia and Sri Lanka could achieve higher growth with a somewhat lower level of investment (Table 2). Two policy messages emerge from these experiences. First, Bangladesh needs to increase its investment to GDP ratio. Second, productivity of investment has to be increased; the case of Cambodia is particularly relevant here.

In the context of investment, a particularly worrisome development in recent years has been the stagnation of private sector investment. Private sector investment as proportion of GDP has remained stuck between 21-22% since FY 2009. Apparently the uptick in public sector investment has failed to crowd in private sector investment. This may be in part because public sector investment overwhelmingly consists of expenditure through the annual development programme (ADP). The number of projects included in the ADP increases at an undesirable pace. This leads to a thinning out of resources across too many projects, most of which are not completed on schedule. As a result, the expected benefits are not realised. A recent review has shown that at the current level of allocation, out of 1,034 projects included in FY 2015's ADP, as many as 154 would take between 6-10 years, 106 between 11-100 years, and 32 more than 100 years to complete.

Apart from inadequate allocation, the other problem that afflicts public sector investment is that the allocated funds are not utilised. Every year, the original size of the ADP as provided in the budget is revised downward, and even then this lower size is not fully utilised.

This leads to delayed implementation and inevitable cost overruns.

As regards to increasing the productivity as well as raising the level of private sector investment, addressing infrastructural and energy deficiencies is a key imperative. Public sector investment is an important pre-requisite in this regard. There are many projects to address these deficiencies, but delayed implementation deters private sector investment. Some glaring examples of such delays are Sonadia deep sea port, Payra sea port, Matarbari coal-fired power plant, Rampal thermal power plant, and liquefied natural gas terminal.

The other problems that deter private sector investment are political uncertainty, inhospitable business environment and inadequate availability of land. Bangladesh scores abysmally low in the World Bank's “Doing Business Indicators” and World Economic Forum's “Global Competitiveness Index”. The programme of establishing special economic zones to alleviate the problem regarding land is yet to gain sufficient momentum.

LABOUR FORCE

Labour is an important determinant of growth. The growth of labour force has made a notable contribution to GDP growth in Bangladesh. In terms of growth of labour force, Bangladesh stands at about the middle position among 12 Asian countries. However, there is reason for optimism in respect to increasing the growth of labour force. Participation of female workers, despite considerable engagement in the readymade garments industry, is still lower than in several other countries (Table 3). Besides, Bangladesh has a high proportion of population in the 0-14 age group. These children will soon join the labour force. The overall population growth remains substantial. These constitute the basis for the oft-mentioned demographic dividend.

The policy implication of the abovementioned dynamics is that Bangladesh should accelerate the growth of its labour force with particular emphasis on increasing the participation of women. Besides, attention has to be paid to increasing labour productivity for which education is an important ingredient (discussed later).

EXPORT

It is generally agreed that export has been an important driver of economic growth in Bangladesh. Export as proportion of GDP rose from a paltry 4.9% in 1985 to 19% in 2014. Nevertheless, this proportion is the second lowest among the 12 countries listed in Table 2. Given the labour dynamics noted above and the progress already attained, there exists immense potential for significant expansion of exports. Moreover, Bangladesh enjoys duty-free access to many developed country and some developing country markets. The actions needed to exploit this potential would include: (a) increasing the share of existing products in the global markets. There is scope for increasing the volume of exports of RMGs, which already account for over 80% of export earnings. The reason is that though Bangladesh has emerged as the second largest exporter of readymade garments, its volume is quite small in comparison with that of China which retains its position as the largest exporter; (b) More attention needs to be paid to the diversification of exports. Several studies conducted by Policy Research Institute show that tariff policies in Bangladesh generally create anti-export bias for new products. Such bias should be eliminated; (c) The government and the private sector should actively collaborate to diversify the markets for exports. As of now, the number of markets for our exports is rather limited.

REMITTANCE

Remittance by Bangladeshi workers employed abroad has made a notable contribution to the country's GDP, particularly by supporting consumption, and thus aggregate demand. Remittance as a proportion of GDP was 2.0% in FY 1985 and rose to 8.2% in FY 2014. There is a scope for further increase in remittance. To realise the potential of this source, it would be necessary to reduce dependence on traditional markets, notably the Middle Eastern countries. No less important is the need to enhance the skill level of migrant workers. Endowed with higher skill, migrant workers could earn more, and thus per capita remittance would increase.

EDUCATION

In order to enhance the productivity of domestic labour employed as well as to increase per capita remittance, greater attention needs to be paid to education. As of 2013, Bangladesh had the second lowest gross enrolment ratio at the tertiary and secondary levels (Table 4). Enrolment at these levels must be increased. The quality of education must be improved and market-relevant skills must be imparted.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Bangladesh has done reasonably well in accelerating GDP growth over time. However, during the last few years, growth has remained static at above 6%. The country has the potential to get out of the 6% trap and raise the rate to 7% and higher. In order to realise this potential, we have to take the following steps:

-Increase investment-GDP ratio through higher levels of private investment as well as cost effective public sector investment;

- Encourage greater participation of women in the labour force;

- Increase exports and remittance;

- Expand opportunities for education in the secondary and tertiary levels, with emphasis on imparting market-relevant skills.

The author is a former Adviser to the Caretaker Government, Ministries of Finance and Planning. He is presently a Visiting Professor at BRAC University

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments