Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is a Retelling of America's Current Cultural Climate

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is perhaps the most culturally significant movie of the last year. In the protagonist Mildred, director Martin McDonagh portrays a woman who's had enough of the town's corruption plaguing her life and decides to do something about it.

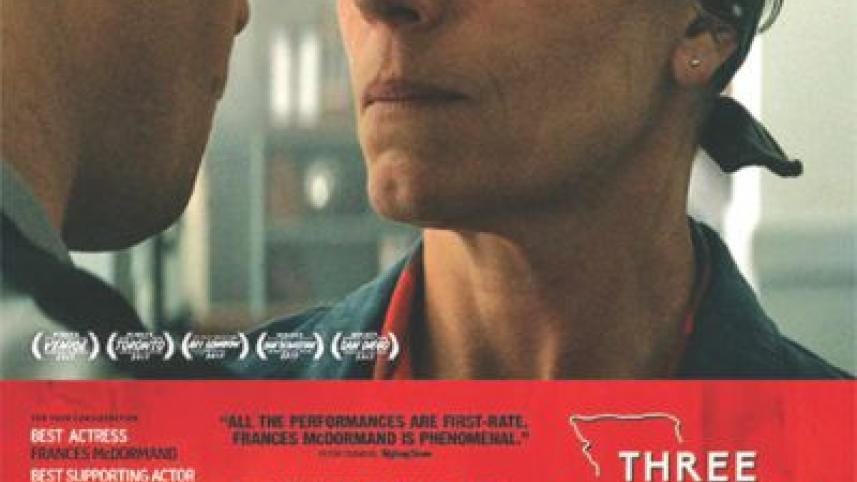

Weaving a tale of vigilante justice with themes of rape, violence and revenge, McDonagh's dark comedy follows a mother, Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand), as she wages war on the local police who have failed to solve her daughter's murder. Angered by the lack of arrests, she emblazons the words "RAPED WHILE DYING. STILL NO ARRESTS. HOW COME, CHIEF WILLOUGHBY?" on three billboards to shame the local lawmen, particularly police chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), for their inaction. Mildred refuses to let her daughter's murder be swept under the rug as an inconsequential act of sexual violence. She is driven and motivated by anger but it also frees her in a way nothing else does. Her fury and resentment is evident in every scowl and caustic remark, always simmering beneath the surface until it hits you full throttle. Then, I had to clutch the edge of my seat as Mildred drills a hole in her bigoted dentist's thumb by day and throws bombs at the local police station by night (among other things).

McDonagh has a knack for injecting even the most serious or tragic subject matters with crude humour. His film In Bruges (2008) is one of my personal favourites because of its enduring ability to make me recoil in horror or laugh out loud in the most unbefitting situations. The dialogues are crisp, sarcastic and delightfully nihilistic, a testament to McDonagh's prominent background as a playwright. This outrageous dark humour laces every interaction, particularly apparent in Mildred's cynical one-liners and sardonic exchanges with the other characters. McDonagh treads a fine line between tragedy and comedy, never letting the film slip fully into either, thus striking the perfect balance. One of the most comical scenes is also the most grotesque as we witness racist policeman, Jason Dixon (Sam Rockwell), haul a bleeding man out of a window to the tune of “His Master's Voice” by Monsters of Folk. (Did I mention that this scene was shot in one take?)

Despite her hatred and cruelty towards others, I found myself rooting for Mildred. Her grief is devastating and relatable to anyone who's lost a loved one to violence. In spite of her immutable rage and sadness, Mildred has her moments of empathy. By the end of the film, she morphs into a vigilante of sorts, donning her trademark blue overalls as she sets out to punish a potential rapist. Only an actress of McDormand's stature could have breathed life into a character as stoic as Mildred Hayes. Her dialogues are cutting but for me, her silence made her truly iconic. McDormand shines during those quiet moments when Mildred stares deadpan into the camera, saying nothing and everything all at once.

Perhaps, the film's biggest success lies in the attention paid to seemingly unnecessary plot devices. Every character, no matter how limited their screen time, has their moments. For instance, Mildred's ex-husband's 19-year-old girlfriend states one of the most profound dialogues throughout the film, “Anger only begets more anger.” Peter Dinklage plays a forlorn car salesman who displays incredible compassion and empathy at a moment when Mildred's actions could have destroyed her life. One of the funniest characters in the film, Jason Dixon, is also the most morally reprehensible as a cop with a history of torturing a black man in custody.

By the end of the film, Jason Dixon and Mildred Hayes's paths merge as we witness a role-reversal of sorts. While drinking at a bar, Dixon eavesdrops on a conversation where a man brags about rape. Believing him to be Mildred's daughter's killer, he promptly dives into investigative mode to help out the woman he's hated since the beginning of the film. Thus, we witness Dixon transform from bad cop to flawed hero in a matter of minutes. By the end, the two have successfully joined forces, a move that seemed, to me, aimed for Dixon's redemption.

I did not find this transformation believable for Dixon. Throughout the story, he is portrayed as an unabashedly ignorant and racist cop with a tendency for racially-charged violence. He stumbles onto bar-room tittle-tattle, and it was depicted to be a strong enough stimulus to change such a morally bankrupt man for the better. As April Wolfe so aptly put in her review at the Village Voice, “McDonagh painstakingly humanises a character who we find has unapologetically tortured a black man in police custody ... and then Three Billboards seems to ask audiences to forgive and forget wrongs like police violence, domestic abuse, and sexual assault without demonstrating a full understanding of the centuries-long toll these crimes have taken on victims in real life.”

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is, by no measure, cinematic perfection. There are flaws, some quite obvious, and interpretations can be many. Yet, when the film ended, I kept recalling the unmistakable hint of hope at the end of Mildred's violence-soaked trajectory. It's the final scene of the movie and in that moment, you know that she is her own saviour. Yes, Three Billboards isn't perfect but it culminates in a satisfying end for a deeply-tortured heroine. It's one of the few films I would rewatch.

Mithi Chowdhury is a soon-to-be graduate of the Institution of Business Administration, Dhaka University and a contributor for Star Weekend and Shout, The Daily Star.

Comments