Sultan's atemporal vision of awakened bodies

"I have no address. Naturally it takes time to find me. I am at all places." This is how the fictionalised S.M. Sultan speaks about his nomadic nature of existence in the book entitled Sultan, famously penned by Hasnat Abdul Hye. The scene unfolds with an SDO (a government official) finally getting hold of the maestro who has long been sought after and could not be found in Narail, though he was supposed to head an art school he himself envisioned in the area. To deepen our understanding of the stylistic and philosophical aspects of this modernist who fluidly traversed cultural cannons situated beyond the modernist tradition, the idea of "existing in all places at the same time" shall come in handy.

The concept of the interstice—which is an in-between space—seems efficacious when it comes to elucidating the life and vision of this modern pioneer. Sultan, aka Laal Miah, in an organic way devised a strategy to simultaneously belong to the past and the present, to the East and the West, to 'here' and 'nowhere'. Due to his unique position vis-a-vis time and place, when Sultan "makes labour visible", he does so by skirting round the cultural-industrial expectations of the contemporary society.

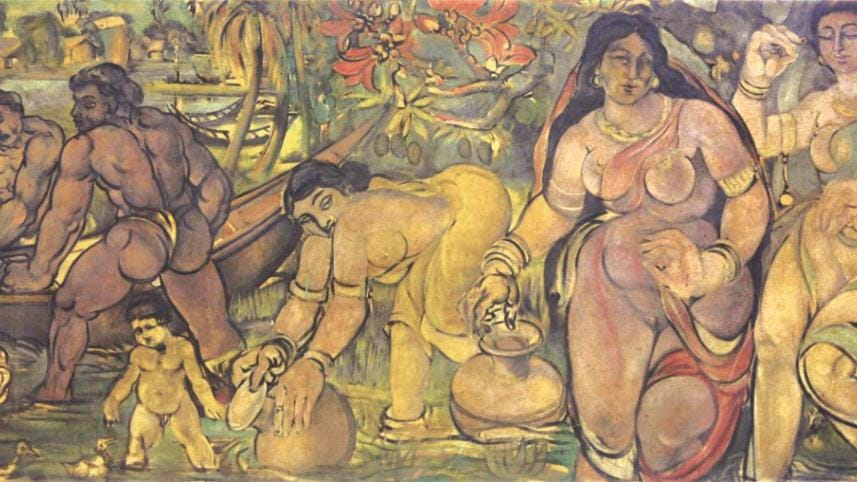

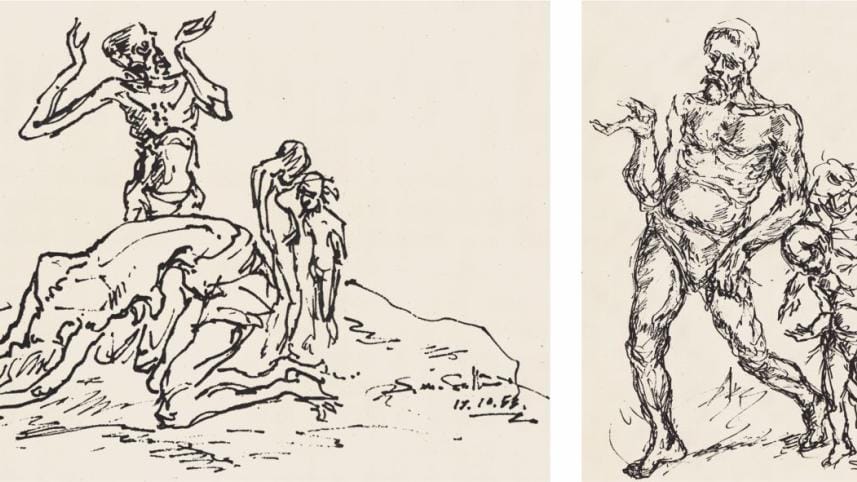

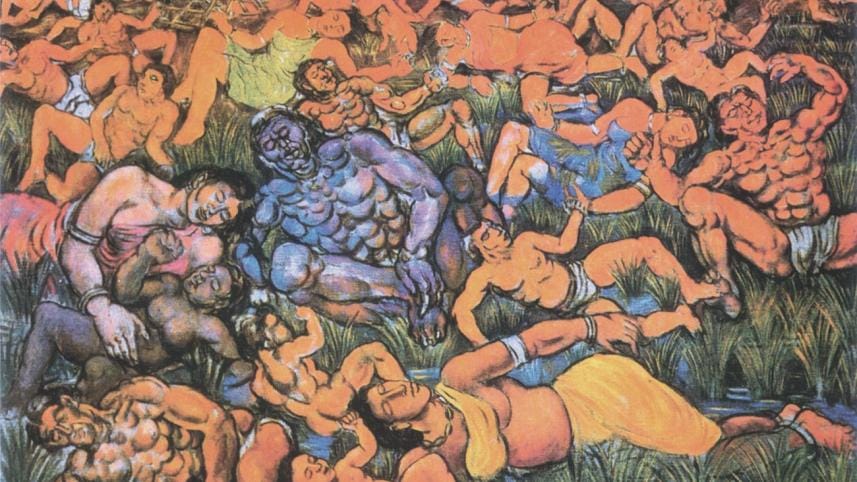

In an "article written by S. Amjad Ali for the Pakistan Quarterly (Year 2, Issue 1) the writer refers to Sultan as a 'landscape artist.' In his view, Sultan was an artist who painted landscapes purely from memory in a style which had no fixed identity or roots" (Golam Dastagir, year 1, issue 2, Depart). No doubt, the maestro made his name by resorting to landscape painting—creating spaces that stemmed from his real encounter with nature, in which he would soon introduce his protagonists, the imaginary peasants. He would also re-visualise them as resistant bodies with augmented muscles to allude to their future potential. The battles he staged between the oppressed and the oppressor sought to undercut the ordeal of the masses as well as the tyranny of the oppressors. The onus of social transformation is unconditionally placed on the shoulders of the people he so lovingly projected as the master of their own destiny eschewing the scenes of violence. To wit, "When I paint violence on my canvas I look at it only as gesture of protest." His, undoubtedly, was a call for social-spiritual awakening.

To get our heads around what is interstitial in Sultan one can begin by mapping his source of inspiration. They come from two seemingly divergent places belonging to the pre-modern times. The murals of the Renaissance Europe, and the murals of the Ajanta caves linked to an Indian Buddhist tradition that spans over eight centuries since 200 BCE, together, one can deduce, forms the basis of his practice. The ambience created with light and shade and is called chiaroscuro in the academic parlance, the muscular figures that verge on the superhuman, testifies to a meditative internalisation of Renaissance art, especially the visual epics of Sistine Chapel à la Michelangelo.

The spirit that surges forth in Sultan's pictorial presentation of bodies that are muscular and in movement/rebellion, can be assumed to have sprung from his negotiation of Michelangelo. The timelessness and the natural exuberance in the restive pieces describing rural lives can easily be said to have appeared out of the Ajanta caves. Time and space, often translated as 'here' and 'now' in modernist diction to emphasise the historical breach with the past, is thus kept at bay to prioritise the vision of a coming community.

Finally, to tap the immaterial sensibilities that went into the Sultanian ethos, it can be safely said that the 'sacred' and the 'secular' has been made into 'one' in his realm. The body or, should one say, an assembly of bodies (since the vision has a social-spiritual dimension to it) are seen as a co-conspirator in change. In Sultan's vision, the represented humans are not merely modern-day 'doers' labouring under the misperception of gaining happiness through material pursuit. They are either living in communion with nature, or engaged in an emancipatory social struggle continually working to re-create the world in order to do away with exploitation of the majority by a few. The latter's stake, visible through the age-old category of 'ownership', no doubt, has taken an absolutist turn under the shadow of global capitalism.

Sultan's peasant population thus forms the tip of the iceberg—what remains hidden below the surface is the sacred, which is the intangible spirit found in all kinds of communion—between human and nature, between the individual body and the society body. What is religious in all this is to found in the 'unreal' (vision of the coming society) from within the configuration of the 'real'.

As for the public figure he was, Sultan's proverbial liminality kept him at the edge of existence. He found his solace amidst the majority population, stationed as he was in his village of birth away from the urban centres. In the early days, he often appeared in public as Radha wearing a saree, with a flute in his hands, or in the guise of a mythic character or even an entity, through which the myth of Sultan has been weaved into the consciousness of the people who began to see him as a sage of sorts.

Born in 1924 into a subaltern family of Narail, Laal Miah or Sheikh Mohammad Sultan died in 1994 leaving behind a legacy which is yet to be put into context. Any avid reader of his images must look at them as interpretable symbols residing somewhere between an allegory and an unfurling of actual rural reality. One also needs to survey them in the context of the historical battles that had been waged against the zamindars and the British colonial rulers by the people(s) of Bengal.

That he was fond of poet Nazrul Islam is not simply a question of taste. Sultan seemed to have drawn a greater portion of his spiritual sustenance from the 'rebel' poet. Nazrul was an interstitial character who categorically challenged the colonial presence by resisting their (mis)rule and the widely circulated knowledge of the colonisers. This was one way of envisioning a free and communistic society for the poet. On another register, his invocation of Nature, Goddess Kaali, as well as the all-pervading yet invisible Creator, have made it difficult for the cognoscenti to delve into his works.

In Sultan, the sage-like humility has taken over the outbursts that we witness in many of Nazrul's politically-socially engaged verses. One finds into the personae behind this depicter of trans-spatial beings representing the peasant population the same social-spiritual eye operational with the hope of seeking justice for the oppressed and permanence of social harmony in a communal life lived in an organic setting. Maybe, in today's finance-driven global economy, this vision seems too utopic. But as an artistic vision that transcends the lived reality and even the knowledge and deshi and foreign technology invested in the creation of this unique vision, what it seeks to perpetuate is the idea of returning to "heaven", a primordial space that we might reconstruct time and again.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist and Editor of soon-to-be-launched magazine Art Plus.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments