Primates of Old Dhaka - Our Neglected Heritage

Nestled in a dingy alleyway at Dinanath Sen Road of Gandaria is a rich bit of history that dates back 103 years. The structure towers over passers-by, facade weather-beaten and yellowed walls bearing the imprint of old age. You enter into a courtyard partially shaded by tin roofs supported by metal planks. The courtyard is deserted on a wintry Friday morning, and yet, the air is static with cacophony. Sadhana's factory premises are buzzing with the frenetic energy of two dozen monkeys at least.

That is the last thing that the average city-dweller would expect to find at Sadhana Aushadhalaya. Jogesh Chandra Ghosh, martyred Ayurveda physician and philanthropist, founded Sadhana Aushadhalaya in 1914. Ghosh, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry and a member of the American Chemical Society, wanted to popularise the use of affordable, herbal medicine amongst the poorer strata of the population. Come rain, hail or the ubiquitous hartal devoted customers come seeking immediate attention from the in-house kobiraaj (ayurvedic practitioner).

But the Sadhana factory is a herbal medicine manufacturer by day and safe haven for the local monkeys around the clock. “I've seen monkeys at Sadhana since the day I began working here. When they cause disturbances in the neighbourhood, people point fingers, saying 'Sadhana's monkeys' are to blame,” says Bhabatush Dey, who has served as the security guard of Sadhana for 17 years. A graveyard stands next door to the factory, providing lush greenery and ample room for the monkeys to run amok. It's not just open space that lure these monkeys to the Sadhana vicinity—it's the promise of food. Bhabatush Dey personally ensures that 10 kilograms of raw lentils are provided for the monkeys every morning at roughly 7 am. This tradition was started by the late Ghosh himself, who would lovingly feed the monkeys every day. Ghosh was shot to death in 1971 by the Pakistan Army for sheltering Bengali Hindu families in Sadhana's factory during the East Pakistan genocide of 1964. Following his death, the factory was shut down for almost a year until Ghosh's son, Dr Naresh Chandra Ghosh, revived Sadhana Aushadhalaya. Since then, his family has carried on this practice and they have yet to miss a day. “When the factory was shut down, there was no one to look after the monkeys. They had to scavenge for survival. But now, they expect food every morning and convene in the courtyard ahead of time,” explains Bhabatush Dey.

The monkeys climb the gate and planks, racing in pursuit of what must be a ball of yarn invisible to my naked eye. They zoom past in every direction, frolicking in the open space. All it takes is a whiff of dry bun and a banana to stop these hooligans in their tracks and furtively make their way toward me, eyes keenly observing the bun in question. Wait too long, and they'll snatch the food from an unsuspecting visitor's hand like a hawk. A dearth of natural food sources around Sadhana entails a dependency on food provided by visitors—the only curb against habitual thievery from neighbouring residences. Concrete buildings mushrooming in every nook and cranny to shelter the ever-increasing human population have fast diminished the number of these primates. The monkeys use overhanging electrical wires to cross busy roads, often being electrocuted. Throw hunger and disease into the mix, and we're looking at an endangered species teetering on the precipice of extinction. Even 14 years ago, these monkeys could be found across 11 areas in Dhaka; currently, their settlements are limited to four areas only, including Old Dhaka localities, such as Tanti Bazar, Shankhari Bazar, Gandaria, Nawab Street of Wari, Banagram, Bangshal road, Jonson road, Tipu Sultan road, Meshundi at Narinda and Farashganj, among others.

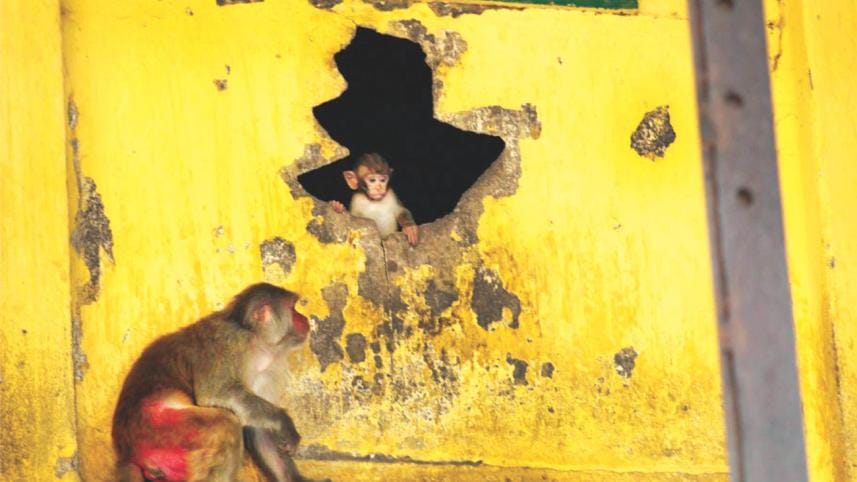

Inconsistency in food supply prompts the monkeys to invade residential buildings, where they enter homes through unmonitored gates or open windows. “In their quest for food, the monkeys often vandalise households. They break into fridges, destroy plants, and steal clothes from rooms and rooftops. The other day, a troop of monkeys from Sadhana ransacked my tea stall and stole a dozen bananas,” chuckles Anwar, who owns a small tea store in front of Sadhana Aushadhalaya. Personal grievances aside, Anwar enjoys having the monkeys around, adding, “Residents get frustrated with the monkeys' disturbance but I don't want them removed from the area. They've been a part of Puran Dhaka for generations, since my father and grandfather's time. They're a part of our heritage.”

The monkeys frequent rooftops in tribes of 10 to 12 at a time, slouching, playing or bickering with one another to their heart's content. I find a lone monkey, sitting isolated atop an iron gate, thoughtfully studying his loyal subjects as they wreak havoc across the courtyard. “They steal clothes, only to return them when they get food. Rowdy as they are, they don't harm people,” explains Sohag Mohajon, General Secretary of Dhaka Youth Club International and an environmental activist.

“The children enjoy throwing food at the monkeys or watching them grab it out of their hands. They're very entertaining!” muses Mohammad Jahid, a local resident of Gandaria who often visits Sadhana with his family. But ever so often, the monkeys' innocent playfulness goes too far, evoking the wrath of the locals. There have been incidents when the monkeys have been sloshed with boiling water or beaten.

The message is clear: the only thing protecting the monkey population is the community's willingness to integrate and accept them. If this delicate balance is ever toppled, the monkeys will be ousted from their century-old natural habitat which humans have urbanised. Thus the question at the forefront of my mind: if this fragile local acceptance is ever breached, what happens to the monkeys?

Ten years ago, Dhaka City Corporation began a feeding programme for the monkeys which promptly increased their numbers to 500 in Old Dhaka. No budget allocation in the later years necessitated the shutdown of the programme in 2013. Local NGO Pokkhikul had undertaken a similar initiative years ago. “Members of Pokkhikul would provide bananas to the monkeys daily. However, they stopped their programme after a year because of rising debt and a lack of funding,” says Bhabatush Dey.

Sohag estimates that there's roughly 100-150 monkeys remaining. This was the very realisation that drove Dhaka Youth Club International, along with Dhaka Women's Club, Puran Dhaka Mancha, and the local residents, to conduct a human chain on December 8. They rallied to urge the city corporation to take responsibility for the rehabilitation, medical treatment and sustenance of the dwindling monkey population. “Unless there's adequate funding to ensure regular food supply and medical help, survival of the monkeys will be threatened. The ministry and city corporation must step in once again to ensure their safety," elaborates Sohag. “The locals too have a duty. A community fund could be set up to feed them.”

My final minutes with Dey are the most telling, though they're spent in silence. He accompanies me outside the premises, yapping at nearby bickering monkeys by way of habit. Familiarity echoes in each of his interactions with them, borne over 17 long years. I'm left with a sense of reverence for our capacity to coexist with these creatures, and the profound consequences if we fail.

Mithi Chowdhury is a dog-loving, movie-watching, mediocrity-fearing normal person. She's also a writer for Shout, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments