Politics of survival: Listening to the (street) children in Dhaka

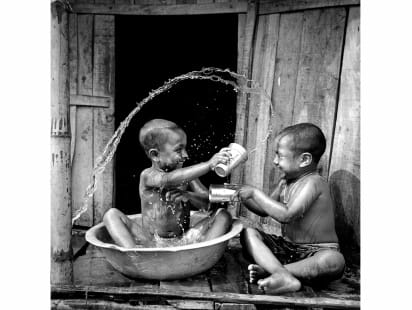

This narrative is not about how adults think of the way (street) children live their lives. This, too, is also not about policy prescription—what we think should be done to change their lives. Rather, this narrative is about listening to the children themselves and understanding the intricacies of their lives in the slums and on the streets, their hopes and dreams in their own voices and perspectives. This narrative also highlights their understanding of the lives they live—which is often linked with raasta, street, poverty, and other forms of subalternism.

Their lives, however destitute it may seem, portray a mosaic of conflict, contestation, struggle, and serendipity. To this end, I offer some visceral reflections on my encounters with (street) children from various neighbourhoods that I visited during my ongoing fieldwork in Dhaka.

It might be important to note here that I put the word ‘street’ within parenthesis because my intention is to not portray a broad picture about the children who take part in the research about their connection to the street, although most of them are. Furthermore, rather than labeling even those who are connected to the streets as ‘street children’, I would like to consider them as simply children, not associating them with any forms of stigma, negatively portraying their childhood, or victimising them.

Mirpur: Power, space, and informality

As I talk to the children—all girls aged between seven to 17-years-old—at a transitional shelter in Mirpur, I learn and discover about their lives. Jonaki, a 16-year-old girl, tells me about their experience living at the 24-hour shelter for girls, which is located in an apartment building. The NGO rents three floors from the landlord for its operation. When asked about her living condition in the shelter, Jonaki says she likes to live in the shelter with the other girls with whom she has built a strong sense of community. But she says the landlord sometimes behaves badly with them. The girls claim he shows no ador, affection, and care for them because they are street children. He scolds at us for nothing, Jonaki says. He also behaves badly with the counselors and teachers, according to Jonaki and the other girls, showing his power as a landlord. Shei jonno apa-ra kichu bole na, that’s why the madams keep quiet (when he scolds at us), says Jonaki. We feel bad when someone scolds us, adds Jasmine, another girl. Her statement is a reflection of the lack of care, love, and attention in their lives because of their marginality. Perhaps, this also reveals a trace of the general (abusive and uncaring) attitude of the mainstream public in Bangladesh towards the marginalised children connected with the streets.

Jonaki says that those who are in power like the landlord are immune from being challenged about their behaviour. Why? I ask. Karon tara-to khomota-shil, because they are powerful, Jonaki says plainly. That’s why we remain scared of these powerful people, adds Jonaki. But we are powerful too, says Jasmine. Amago power (in English) Mazhar-e, our power is in the Shrine, she says. Eikhane amra raja, keu amago kichu koite shahosh kore na; korle iit marum, here we are the boss, no one dares to say anything to us—we will throw rocks if they did, Jasmine adds, beaming with excitement and proud.

The Mirpur Mazhar (Shrine) in Dhaka is a unique place, a theatrical stage, where many (street) children produce and reproduce their lives. Most of the children who live at the transitional shelter come from the Shrine, where they have spent most part of their lives. In terms of power dynamics, informality, and spatiality of children’s everyday lives that are uniquely different between the shelter and the Shrine, a mere half kilometre away from the shelter, the Shrine is an interesting place to be further revealed. The girls offer to take me there for a visit. I accept it. I will need to explore the Shrine that represents so many dimensions of their lives and unique tales about the way of life there, a place (in terms of everyday visit for mass people) and space (in terms of the children’s situated-ness) where formality (the practice of religious rituals and deity) and informality (a place to live and leave) converges and diverges. For the children, most importantly, this place represents power, through a sense of ownership.

Dhanmondi: children’s agency to act on their cognisance

On a clear sparkling afternoon at Dhanmondi Lake, one of the most popular and well-known parks in Dhaka, I sit with Bilkis, a 12- to 13-year-old girl, who spends a considerable amount of time in the park, sometimes selling flowers and chocolates, sometimes just hanging out with the other children. The encounter brings about a number of issues—her work, decision-making, and resiliency. Often, she sells chocolates in the park. She gets them from her father. Whatever Bilkis earns from selling the chocolates, she buys food for her households, sometimes to ensure that she gets to eat at home. Her parents are not home always—they work. Since they have to be away, Bilkis’ mother has taught her how to cook. So, whenever her parents are not at home, Bilkis cooks rice and fish and shares them with her younger sister. She is not selling the chocolates today. Why aren’t you selling today? I ask. Iccha nai, tai, I just don’t want to, she answers nonchalantly. What are you going to eat at home? I ask. Jani na, I don’t know, she pursed her lips. My mum will cook whenever she returns, she adds nonchalantly.

Another time, I come across two children, one boy and one girl, both appear to be 10 or so, who are selling red roses in Rabindra Sorobor, an amphitheater, in the same park. As I sit alone on the circular brick bench that faces the main stage, jotting down the notes from my recent interviews, the young flower sellers come toward me. For a brief moment they scan me and my sides, and then they proceed to move away. Ki ful diba? Can I get a flower? I ask. Apni to eka, you are alone, replies the girl. I immediately break into loud laughter. They give me a puzzled look and leave. In the park, there are many young (seemingly) unmarried couples spending their moments of togetherness in a culture where dating or spending time together alone in one’s home is heavily stigmatised. So, parks usually provide young lovers with a space to spend time together. I am alone. To the flower sellers, I am perhaps not a good candidate for buying flowers. I am really appalled at their smart salesmanship and buddhi, intellect, at their tender age. I wonder what would have become of them had they had an opportunity to grow up in an affluent family.

Korail: vulnerability and ‘odhikar’, rights

The children who grow up in Korail slum, sprawled across 130 acres of land near Gulshan, one of the poshest neighbourhoods in Dhaka, are susceptible to illegal activities such as drug addiction and petty crime at a very young age. Children who do not have families or guardians to look after them often spend considerable amount of time on the street. Hence, they are at risk of getting involved with madok, drugs. We are considered kharap, bad, when we are on the street; everyone looks down at us, says a boy in Korial slum, who spends a considerable part of his day on the street. Amra to iccha kore rashtai ashi na, we don’t come to the street on our own, says another boy. Amra gorib, tai ashi, we are poor, that’s why we come to the street, argues the boy matter-of-factly. Yet, among uncertainty, risk, and vulnerability that are part of the everyday lives of the children, hope still exists. To make a point about how a group of children I interviewed view their (imaginary) world—a temporal place that is different from their bastobota, reality, on the street—I describe the following. This is their odhikar, rights, they told me:

We want to be in a world full of angels where there are no lies, no dishonesty, no sorrow, no insult, no beatings; where everyone —‘choto’, young, ‘boro’, adult—is considered to be equal; where life is built on love and affection.

A few afterthoughts

Although based on strictly visceral reflections, I offered some glimpses of empirical evidence of the informal lives of the (street) children in a city where power dynamics between the adults and the children, informality of the city and its many spaces and places, children’s (lack of) agency and rights play a critical role that signifies the reality of the everyday lives of the marginal children whose lives can also be intricately connected with the street. In this vein, I have attempted to suggest that context is a critical factor in research about and with (street) children to understand their lives.

All names have been altered to maintain anonymity of the children. Iqbal Ahmed is a doctoral researcher in human geography at Durham University, UK currently conducting his fieldwork in Dhaka. He can be contacted at iqbal.ahmed@durham.ac.uk.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments