Kafka in the age of the internet

"I see, these books are probably law books, and it is an essential part of the justice dispensed here that you should be condemned not only in innocence but also in ignorance."

There is comfort in metaphors. Something about great literary works provide us with a sense of safety – maybe only an illusory control through understanding – when the world around us seems to be flipped. After Kellyanne Conway, the current Counsellor to President Donald Trump, famously coined the term "Alternative Facts" to refer to the age-old tradition of blatant state lies and propaganda (the war in Iraq for example), sales of George Orwell's dystopian 1984 surged – topping Amazon's bestseller list and at times sales increased by almost 10,000 percent. Earlier, in 2013, when there was widespread reporting of the US government's mass data-collection programmes, the sales of 1984 had reportedly increased by 7,000 percent.

It is easy to understand why. 1984, is a world of doublespeak, where day is night if the government wants it to be, where one finds the anti-utopia of the most blatant scenario of mass surveillance. Replace the world of spying televisions with spying webcams, and the jump to a world where no thought is unmonitored is easy to imagine. A fitting metaphor for this world we do not understand. A world where Jeremy Bentham's perfect prison, the Panopticon, is a reality. Here, power is effective because it is visible but unverifiable. Like the Panopticon, in this world, you do not know you if you are being watched, but you you live "in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and except, in darkness, every movement was scrutinised." (1984, George Orwell) The bleak world of government power found recourse in Orwell.

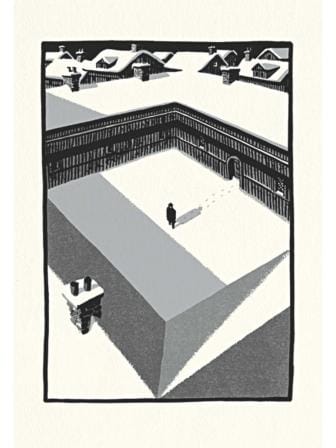

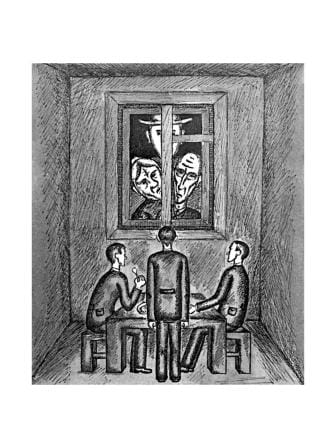

But to frame surveillance in the Orwellian is to leave out a big chunk of what it entails. Orwell's world is of total authority on the individual life; it misses the issue of the data we give almost willingly, and the collection of which does not directly correlate to an issue of freedom of speech. Because the issue of privacy in the digital age transcends beyond the censorship of speech, a better analogy for the world we live in today is Kafka's The Trial. In Kafka's world, things inexplicably happen; in The Trial, the main character, Joseph K., wakes up one fine morning and finds out he has been arrested. His guards, who work for some authority which remains unnamed, inform him he is under arrest. His charges are not named, neither are his accusers, and K, though initially nonchalant, can find no trace of what he has done wrong. The mysterious Court, which is overseeing his case and where the judgement of his guilt it seems has already been assumed, cares little of confining K. It does not even force on him any obligation: he is free to come to the court if he pleases. The world surrounding his trial is one of secrecy. His only links to the court are through its lower officials, the Advocate, his maid, or the official Court Painter; and they, too, only tell him that they know little about how The Court functions. K. cannot figure out why he is being accused. The entire process of the proceedings happens in the shadows, of which K. can glimpse only parts. This is a world of a cult or an ancient religion, where the uninitiated knows little of what goes on. The bureaucratic labyrinth, the secret laws and mysterious court officials hopelessly entangle K. in a trial which he tries to fight, resorting to whatever means he can. Towards the end, a priest, also a court official, tells him the parable of the doorkeeper who guards the doors to the law, and entry to which is forever restricted to a man who seeks to go in. Without warning, one night, K. is taken away and executed.

***

"Judgement does not come suddenly; the proceedings gradually merge into the judgement."

One should not take a metaphor too far. It isn't in K's execution or the exact process of the court proceedings that Kafka is relevant today. Yet, reading The Trial, one cannot escape an eerie sense of recognition. Surveillance today is not only about targeting dissidents and the free press: the issue is that we do not even know what data is being collected. We do not know about the bureaucracy and the laws and courts that decide who can take what data from us, and how they are used. And it is not even only the government that is interested in one's private life; corporations such as Facebook and Google collect data and make the decision about what ads and search results should pop up on someone's newsfeed. How is this data stored? Does one have a choice to opt out of it? And by clicking the "I Agree" on the terms and conditions page, what personal information are we agreeing to share? The feeling of helplessness and powerlessness in a vast process outside oneself is what makes Kafka eerie reading.

The debate about privacy in terms of the Orwellian leaves out this distinction. Daniel J. Solove, Professor of Law at the George Washington University Law School in 2001 was already stressing the importance of the Kafka metaphor when it comes to understanding the legal debate about surveillance and privacy. In a paper titled Privacy and Power on the Stanford Law Review, he writes: "The Trial captures the sense of helplessness, frustration, and vulnerability one experiences when a large bureaucratic organisation has control over a vast dossier of one's life At any time, something could happen to Joseph K.; decisions are made based on his data, and Joseph K. has no say, no knowledge, and no ability to fight back."

In a subsequent work, published in 2008, Solove argues that the widespread justification of surveillance based on the premise "if one is not guilty, he has nothing to hide" takes a narrow approach to the idea of privacy as a right. It is here he thinks Kafka is important; for him it is not whether the collection of data is necessary, but what control and oversight exists in this process. He writes, speaking of the storage, use and analysis of the data collected, in his paper "I've got nothing to hide" and Other Misunderstanding of Privacy:

They affect the power relationships between people and the institutions of the modern state. They not only frustrate the individual... but they also affect social structure by altering the kind of relationships people have with the institutions that make important decisions about their lives.

So a view which defines privacy as "hiding bad things" shifts the debate away from the issue about what legality a state or corporation has of sifting through one's data. For Solove, Kafka's The Trial poses a more fundamental issue: it is not only uninhibited behaviour that is at stake, but the exclusion of an individual from the knowledge and participation in the use of their data.

***

"After all, our department, as far as I know, and I know only the lowest level, doesn't seek out guilt among the general population, but, as the Law states, is attracted by guilt and has to send us guards out. That's the Law. What mistake could there be?"

In The Trial, Kafka creates a world of exaggeration which contains the truth of one's disempowerment. It is far away from a world where government's need to justify their suspicion and be accountable to a court when infringing on one's privacy. When the surveillance debate has been framed around the vague notion of national security, it takes our data, from fingerprints to household income information, without giving us any idea of how it will be stored, who will use it, and why. The law seeks guilt, and it is right because it is the law.

It is interesting to note in passing that Milan Kundera once called the spiritual condition of man in a totalitarian state Kafkan. "There are tendencies in modern history that produce the Kafkan in the broad social dimension: the progressive concentration of power, tending to deify itself; the bureaucratisation of social activity that turns all institutions into boundless labyrinths, the resulting depersonalisation of the individual." (Kafka's World, The Wilson Quarterly) Maybe, the world today is not Kafkan in the same sense he meant (for he lived in a different world). But it is all the more Kafkaesque in our lack of control. Is the choice to opt out of using Google or Facebook even a real one for us? How many of us understand the dense legal language of the laws which gives authorities the right to read our data? The justification of unrestricted access to our data because of national interests leaves us no choice but to acquiesce.

So where do we go from there? After all, 1984 ends in two lovers denouncing each other, while The Trial ends with K.'s execution. No power is dismantled, and K. dies not knowing what he did wrong. The two books give us a frame of reference to understand our world today; they provide some comfort. They are not solutions. They can only highlight what is at stake, and as Solove suggests, help us frame our argument in opposing unrestricted constant watch through helping us understand a pluralistic view of privacy. Or, in the age of social media, help us understand and demand that participation in what corporations get to do with one's data. It is not only about being put on the docks for a crime, but, about this participation in the power structure, which now favours the state and big businesses.

Moyukh Mahtab is a member of Editorial Department, The Daily Star.

Comments