Into the Fold, Out in the One

As a reconnaissance of what seems like a neural landscape, Soma Surovi Jannat's oeuvre seems to hover over the "plain of immanence" perceived as Spinoza's "single substance" (God/Nature), thereby, lending it a distinction any artistic endeavour seeks to attain. Yet the imageries are entwined with this singular presence that is referred to as God/Nature. If the imageries work like an extension of this "whole", which is "pure reality", they preclude the notion of representation to embody a unified vision. Thus her images serve as an entry point into a complex relational web. Additionally, their forming into being annuls the Cartesian duality of the mental and the actual.

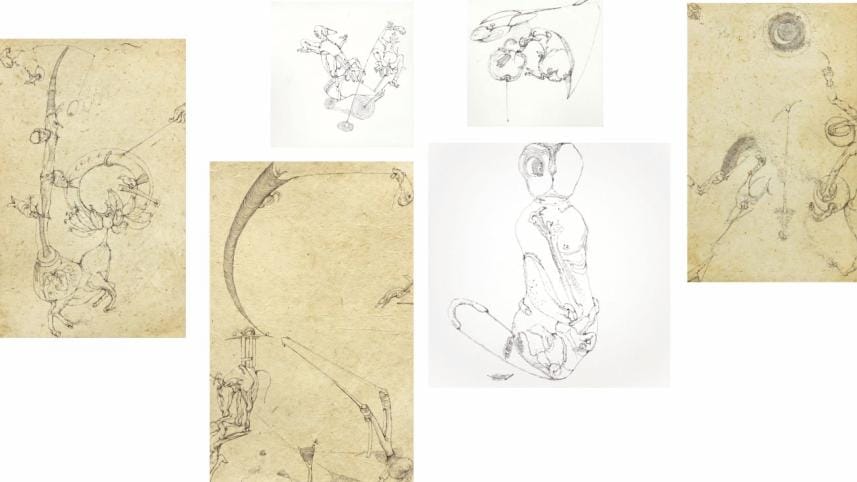

As for the interconnected motifs, they carry features one can recognise, though, maybe, often left a bit mystified about their context. If being in the midst of things (man-made and natural) has set the creative process of this young artist on the move, one can be sure about their sources. An array of figural motifs and objects can easily be detected—though most are often found in their respective states of mutation. With the recognisable being modulated by the power of the mind, what one is left with are psychologically fraught images. Thus the (ill)logic of expression, any one would attest, defies easy explanation, one which takes viewers back to the question of "single substance".

It seems as if the visual and conceptual elements have been poured into the artistic space like mortar into a spontaneously structured building. They are invested in a series of imaginary architectures. In each, one discovers several plains, various twists and turns through which a sense of "being" is established rather than meaning.

Since the final imagery oscillates between what we perceive as human and nonhuman, or natural and unnatural, the position of the artist in relation to her creation remains veiled in mystery. Perhaps this is intentional—the object here is to free one's senses from the bodily (pre)occupation. It is an ultimate abstraction that conventional formalism had never sought to achieve, whereas Surrealism had once cultivated as its main vocation.

To demystify the artistic diction, one thus feels compelled to return to the origin—the lived experiences on a given terrain—Santiniketan, the place where Jannat was resident during her studies. She has developed her work savouring the luscious beauty of the landscape of this slowly changing rustic region that still retains some of its sublime features. The sense of "emptiness" that casts a mythic spell on her images is directly derived from the landscape she experienced during her Master's at Visva Bharati.

Peering into the world of this unconventional young artist, one wakes up to some of the recognisably displaced, dehierarchised natural and man-made elements—as is evident in most of the works.

In one image a mother bird is feeding her chick. Morphed in a way as if in a state of mutation, the bird and the chic seem "unbirdly" at times, transformed as they are under the machinations of an absurd condition, or so it seems. They are shown under a disjointed landscape. The scene hides in its folds some of its true meaning. In fact, this interesting interplay between concealment and unconcealment prompts the young Visva-Bharati educated artist to appear in the role of a conjurer of semi-fantastic, quasi-absurdist imageries. She is visibly working from a slightly different register than the absurdist mode we had once witnessed in early Ronni Ahmmed.

The series produced under the rubric Grey Contours is an attempt to work "with the world"—mostly real, often absurd in its constitution and always unfathomable in its breadth and depth. Thus the otherwise recognisable forms of human, animal and man-made objects are rendered unfamiliar. They are debased from their actual morphological structure and are subject to manipulation of the imagination stretched to its limit. For example, in a particularly quirky work a ladder grows unimaginably tall while its lower end tapers off to a vanishing point. Even the process of withdrawal has a place in the artist's aesthetic stratagem—we witness objects that are left incomplete with some parts of them unpredictably collapsing into mere pen marks—the main mode of expression.

The poly-valence that this young artist is able to achieve seems effortless and the multiple plains that she makes visible exploring the livable and unlivable worlds seem like an upshot of an unconscious understanding that the features of the livable world that we often construe as "real", are apparently "imposed on the world by the human perceptual-cognitive apparatus."

Mustafa Zaman is an artist, critic and editor of a+.

Comments