Iconoclastic figurality in Shahabuddin Ahmed

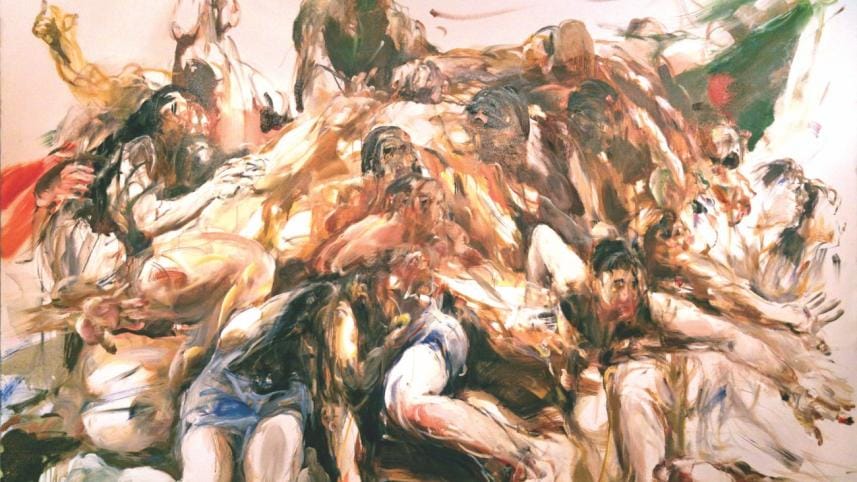

Alpha male striving to take on the future by breaking free of the bounds of the existential matrix—this is how a Shahabuddin addict might try and unhinge oneself from the "rote understanding" of his scampering, hurtling males for which he has made a name, at home and abroad. The suggestive tryst with the future—which is the metaphorical premise of the figural motifs—is evoked in myriad postures in his paintings of the last 30 or so years. Variously explored in oil, this pattern of visual proposition can simply be defined as "aspirational" where hope is plumbed against the impossibility of our violent time. In the recognisably bold rendition of male figures, there appear "grains" to talk about in relation to a project of emancipatory implication: in each imagery optimism is made flesh and the mythic possibility of human enterprise is unveiled against the uncertainties of life. There is a sense of desperation that leads to the distortions, or vice versa.

Treated with oil gestures, a typical Shahabuddin piece also explicates what is known as "truth to material". Built up through the application of paint-heavy brushworks by way of a performative engagement with the canvas, each image works like a mirror to a shifting, moving imagery where broad sweeps of brushwork comingle with the resonating surface created through the accumulation of thick layers of paint. It is this painterly quality that lends sufficient "materiality" to his imagery serving as a point of entry into the final artistic vision.

The two corresponding elements—one pertaining to the visulisation of the spirited male bodies and the other of paint made into body—together form the much familiar Shahabuddinian lingo. His is an artistic dispatch about which there exists an array of nationalist rhetoric, but no authentic narration to attempt a serious unpacking of the symbolic meaning of his figural motifs or an extensive analysis of the language he has repeatedly used.

It was architect and art critic Shamsul Wares who, in a rather informal gathering, once questioned the situatedness of Shahabuddin Ahmed's running, gesticulating figures. His contention was plain and simple—the figures of this modern master express a recognisable ambivalence by not bearing any obvious signs of belonging to Bengal or Bangladesh. This very argument, though nationalist in cast, easily lends weight to what we can now dub as a "local hermeneutics" which may unfold once the languages negotiating the rural art forms are pitted against the works based on Western academic and avant-garde learnings. In addition, the same argument also opens the issue of Shahabuddin's linguistic expression out to the questions of aesthetic stratagem—which, no doubt, seeks to transcend the limits of lived experience.

To top it all off one can declare that art serves as a space for the creation of "otherness" through which to enter a symbolic realm rather than slavishly working out a visual solution from within the confines of the real.

An artistic act carries the seeds of transformation. The epiphanies that art invokes work against mercantile day-dreaming. Such awakenings are part of a process of spontaneous realisation of the "self" comparable to what religions, spiritual guidance in their nonspurious forms have to offer. And, of course, in the post-religious, post-epiphanic Capital-driven age, following modernism's total incursions into the far corners of the earth, art often serves as a site of salvation. Realised mostly against the centralised, politicised national/cultural ethos art also negates its correlates including the social-political logic that apparently echoes old-school religiosity and its attendant symbolic order, though inspired by a somewhat fluid but ethically problematic "metanarrative". If Shahabuddin's place on this consecrated horizon has been sealed through his success in bringing into view epiphanic moments, his tendency to repeatedly produce the same humans with cricket bats in hand or bearing some such perceived symbols of national pride to inspire collective passion, simply bores holes into his artistic project.

No doubt, unsituatedness is in itself an authentic artistic strategy—one that had once given rise to the European avant-garde movements and their myriad subtreams that gradually appeared across the world. These new departures also included the contextual modernism that blossomed in Mumbai, Kolktata and Dhaka in the last century. Even the concept of the "local", or indigenised modernism, for that matter, stemmed from the will to unsituate oneself from the comfortable perches the urban centres had once sought to establish for the creatives. This later phenomenon is the handiwork of the artists who boldly melded the spirit of the avant-garde with the cultural specimens of rural origin, as is evident in the pioneer modernist Quamrul Hassan.

Consequently, one can defend Sahabuddin in lieu of his strategy that still seeks to express a state of insubordination to his lived reality. A young dramatist and art writer Shahman Moishan once exclaimed that most of Shahabuddin's works reach an epic dimension and they even defy the bounds of the gallery space they occupy. It will not be an overstatement to pronounce that the artist places his figurative constructs within a space that simultaneously echoes eternity, unbridled human passion and a futurity that awaits unfolding. He accomplishes this by setting the figural motif against the vacuum of the imaginary space.

The effacement of traces that might lead the viewers to the familiar elements of the land and its people is not a constant in Shahabuddin's oeuvre. We have seen how, over the last thirty years, he has dealt with migrating groups of people, and also portrayed Ghandhi, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and even Maulana Bhashani in their respective garbs. Though the colossal political icons are made somewhat unfamiliar by heavy oil gestures, and sometimes even dwarfed by the vastness of the painterly space they are intentfully set against. The migrating people too are rendered otherworldly and can easily be likened to near-mythified scenes of great exoduses of the past civilisations.

French art critic Gerard Xuriguera had once put Shahabuddin's strategy in a nutshell: He "did not turn into a militant painter, but simply a painter, a painter that always cared more for painting than for the subject of his painting." This fact seems to afford an alteration of the bodies he represents. When he chooses not to home in on the particular, his figures assume a symbolic pattern, looking more like visual indexes of paralinguistic implications. The Alpha males—those that look sturdy and spirited and are placed along the continuum of the tumults of the present and an unknown future—they traverse a mythic space in alignment with the expressed tension between "here" and "nowhere". Shahabuddin's fluid articulation accentuates the anxiety.

The romancing of the motivated bodies captured in flights across an unrecognisable space in an indeterminate time seems to demand the mythic dimension he cannily achieves. This, perhaps, is a way for the artist to envision his protagonists as denizens of an emergent reality, rather than as bodies trapped in actual spaces. Still, in Shahabuddin's works the moving, gesticulating bodies, though deterritorialised to the max, remain inalienably attached to the universal concept of the bhumiputra or the organic man of the earth. The colour brown, which is Shahabuddin's signature hue, seems to extend its "aura" of earthiness to defend his case emphasising a symbolic link bet ween man and his context. Therefore, the singularity of the image—built chiefly around the lone male body in each canvas—often gives the impression of being part of a larger social vision. They display, by coming into being, an irrational will to break free of the worldly shackles with the hope of mobilising "social solidarity".

It is in this context that the "metaphysical" intersect with the "historical" – each individual body is thus recognised as that of a muktijoddhha or freedom fighter who now extends his zeal for freedom to the economy of paint and brush. The sign of the body becomes easily aligned with the memory of a war that the artist himself fought to unseat the oppressor elites of the then West Pakistan.

Shahabuddin's past role as a freedom fighter during the nine-month long war thus haunts his imagery in a not so unholy way. Rather than codifying his works with trauma and hauntings of worldly origin, his works smacks of emancipatory vision. Though, one must also acknowledge that "everything here [is] translated simultaneously [into] the irrepressible power of movement and raw violence" to quote once again Xuriguera who wrote quite a few substantial pieces on the artist. A tribute in the shape of a cover story appeared in the French art magazine Cimaise, early 1990s.

The raw violence is nothing but passion made flesh—the ghostly substance that escapes the dominating, ruling gaze of the ideologues or gatekeepers. The Shahabuddin we celebrate lies at the intersection of nature and culture and is not only recognised through the "anthropological difference", but also by way of the particularity of his artistic achievements impetused by the collective regeneration that had taken place during and after the liberation war. This is the locus where the schema of transcendence looks the nationalist-populist vision in the eye.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist and Editor of soon-to-be-launched magazine Art Plus.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments