Articulating Life as It Unfolds

One of the pioneers of modern art in undivided Bengal, "Shilpacharya" Zainul Abedin (1914-1976) represents the mid-century "realist" trajectory that began to unfold in many modes and sequences—first in Calcutta (now, Kolkata), then in Dhaka following the partition of India in 1947. The division of Bengal along religious lines resulted in forced migration. Following spates of communal violence, several Calcutta-based artists of all-India fame made Dhaka, the then capital of East Pakistan, their new home. Zainul's life in the new city had to go through a reorganisation. Since the region lacked a modern art institution, he, with the support of his peers, became engrossed in building one. The formation of Dhaka's first art college in 1947, which is now the fully-fledged Faculty of Fine Arts, Dhaka University, was a seminal event. The place of art education soon became the centre of constructive political-cultural regeneration.

Zainul's career became intertwined with the emergent new Bengali identity politics, though his humanist vision remained nonparochial and inclusive. Emerging from the cultural mix of Mymensingh, the rice-producing heartland of Bengali culture, he found himself at the centre of artistic activities in Dhaka carefully choreographing his actions. He aligned with the socio-political struggle against the hegemony of the West Pakistani ruling elite, but, without risking a falling-off from the course he devised.

On the registers of art some remarkable curves provide us with clues through which to appraise the master's impact on the cultural patterns of East Bengal. His insertion of rural art into the urban educational space is an example of his various impactful mediations. Zainul set the stage for the urban, educated artists to be inspired by the art forms of the masses. By inviting rural artists to stage two consecutive fairs in the then government College of Arts, since 1953, he laid out the approach for convergences that would soon begin to preoccupy some of the most talented artists of his time. Works of Novera Ahmed, Quamrul Hassan and Rashid Choudhury since the late 50s are cases in point.

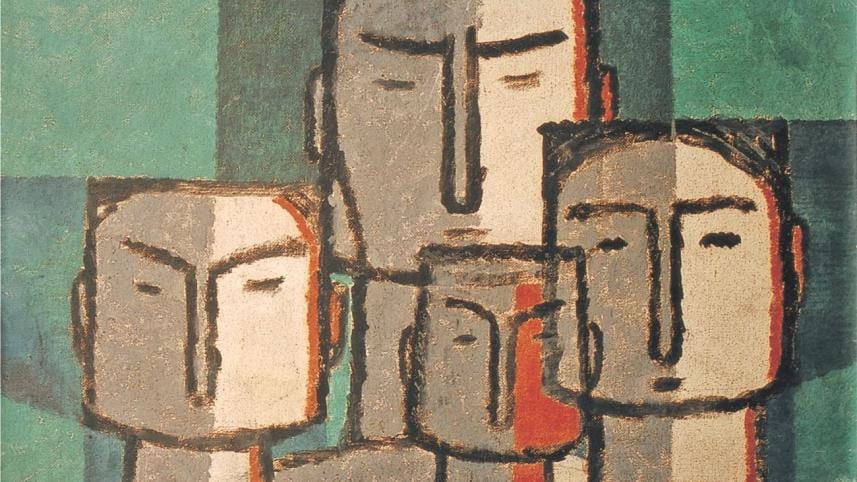

In Zainul's itinerary, the above inclination resulted in the melding of the western and the local traditions. In his own artistic capacity, the linear strategy of shora chitra was brought to bear on formal experimentations. The result was a series of reconfigured human forms—tightly geometric in composition. But he was quick to abandon this new method since the stricture of composition seemed to have stolen the life or verve out of his work, one which he so earnestly wanted to effectuate. Zainul had a clear inkling of his metier which, he realised, lied in realism rather than in attainment of affectation—the latter is always tied to stylistic rigour. As opposed to such visual gambit, a dynamical relationship between lived experience and art informed most of his representational paintings. This was apparently his non-schematised scheme on which his art rested throughout his life. It helped him lay the ground for his life-long attachment to the plebeian life and the existential rhythm the masses blissfully embrace and the fallout they intermittently endure.

Zainul's realism hinged on an unaffected depiction of the sensory realm. Without romanticising the ordinary people, he captured them in their everydayness, glorifying the rural context.

The intervisuality, one which commences from negotiating multiple sources of invention and representation, had little sway over Zainul's oeuvre. Though the academic learning in western illusionism served as the basic premise, his was a "realism" where empathy met with the unreserved pleasure in the ordinary and the mundane. So to define his realism one must resort to the idea of dehierarchised, postauratic image making, in which the authorial control over style never leads to the expression of grandeur. For Zainul, grandeur seemed superfluous—a veil that comes between art and life. Like his tongue, his brush spoke in the vernacular since he had little patience for stylisation via enculturation. The geometric phase mentioned above—one which surfaced since his return from London where he attended the School of Slade for two years—lasted only two years.

Zainul's idea of 'image' precludes aestheticism—a category that lifts the image out of its actual context and places it at the top rung of the hierarchy of taste. He initiated a gaze shift by placing his canvases next to the ordinary people.

The Famine Sketches, responsible for his rise to prominence during his early life in Kolkata, was the result of an empathetic response to a man-made disaster. His preoccupation with humanity's volatile aspects began with the series. He rendered them in 1943 in response to the Bengal Famine of the same year. The tragic event saw the emergence of "historical consciousness" in him which was otherwise absent in Zainul's landscape paintings of the formative years. He was only 24 when he effectively employed his realist vision as well as skill to memorialise the historic human tragedy that brought to light the dismal inconsistencies of the colonial rule. The natural calamities that undercut the very rhythm of life appeared to have enforced similar copulation in the master to respond. In fact, his ambitious works—the memorable masterpieces—are based on the struggles of the people to transcend all kinds of depredations.

The Kolkata phase of his career, the 1930s onward, in the short span of his student years followed by his stint as a teacher, saw Zainul emerge as an accomplished draughtsman. He soon became well known amongst his peers for his extraordinary artistic ability. The graduation from a devoted learner to an accomplished artist took only a few years of rigorous training. As a student of art whose occasional engagement with social-political activism subsequently made him re-adjust his focus on the art-life nexus he persistently relied on, Zainul survived by way of contributing artworks and illustrations to the newly established newspapers and periodicals in Kolkata—those that answered to the needs of the emerging new Muslim educated middleclass. Every issue of Millat, a weekly, carried Zainul's landscape. The daily Azad also employed Zainul and many other Muslim artists in their effort to bring out an Eid issue.1 These networks coupled with his stint as a teacher at the Government Art School since 1938, re-affirmed his position in Kolkata.

As for his humanist position, his proximity with the other two Bengali Muslim intellectuals who stood for a mixture of "secular and broad-based philosophy"2 and the cultural ferment of East Bengal he indentified with, emboldened his voice. In Kolkata Zainul's link to his birthplace saw its affirmation through his association with his deshi or local brethrens—singer Abbasuddin and poet Jasimuddin. If his political vision sprang out of his love of the land and its people, the influence of the left-lenient writers, artists and political activists, helped him develop a humanist position, which in turn prepared him for the memorable series of drawings that now comes under the rubric of Famine Sketches.

Zainul's role was of precursorial nature: his praxis set the stage for what we now understand as the dominant patterns of Modern art which gradually emerged in the urban centres across the region. If his influence is relatively less palpable in the outward-looking modern artistic dictions, expressed in the "excessive subjectivity" of their languages, to quote John Berger, it is clearly legible in its indigenous variants.

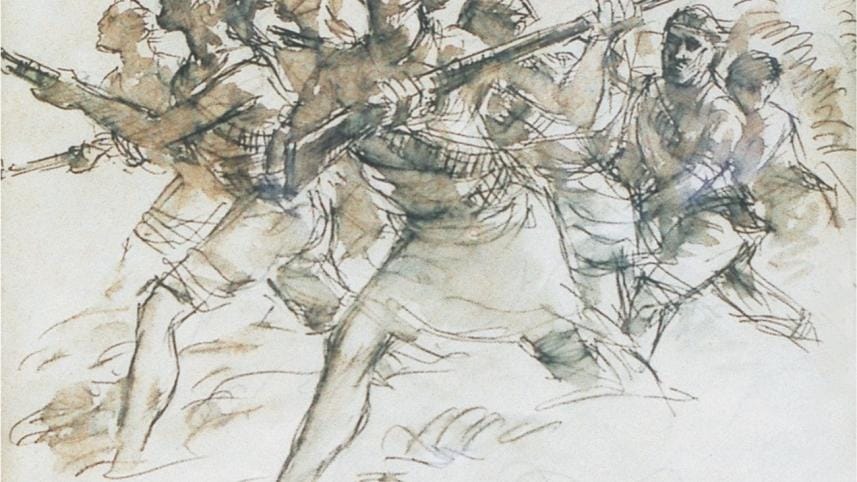

After surveying the works of Zainul's entire career spanning little more than four decades one is able to notice several interconnected oeuvres that appeared in sequence. One sees a beginning when Zainul became known for his acumen in portraying the bucolic life; the early signs of change in 1943 when in his powerfully brash linear method was employed to memorialise the victims of man-made calamity that was the Bengal famine; the short-lived geometric phase in 1953 following his return from a two-year sojourn in England; and lastly, the return to the immediacy of bold brushworks and expressive figural motifs which saw a new technique at work—sketchy lines achieved through candlestick overlapped with stark black sweeps of brush dipped in Chinese ink. The final method first appeared in the panoramic Nabanna (1969), and later in Monpura'70 (1973), where sparsely applied brown and yellow comingled with the linear rendition of humans and other recognisable forms. He applied the same technique which redefined his language through the simultaneous application of negative and positive lines in some of the portraitures including the famous visage of Maulana Bhasani, and in a particularly murky version of the raging bull, as well as various other types of formal experimentation with human figures. In one of the few works that Zainul did on the theme of muktijuddhas or freedom fighters one is witness to the impassioned application of the candlestick employed to achieve the fluid cluster of figures.

Zainul Abedin's patronage and organizational capacity spread across a wider field of cultural interests. His collection of rural art objects testifies to his acute awareness about the ravages of time. His love of the folklores turned him into an unapologetic connoisseur of the traditional crafts, kanthas and clay-dolls. And this growing habit finally extended to the establishment of the Lokoshilpa Jadughar, or Folk Art and Craft Museum in Sonargaon, launched in 1975. His efforts gradually made the cultural elites of Dhaka aware of the value of the rural crafts. By organising the first-ever mela or fair of folk art at the art college premises in 1955, he sensitised the urban minds to the vigour and relevance of the existing rural art forms.

Zainul Abedin, the Shilpacharya, or the Master of Art, will remain forever etched in our collective memory for his art as well as his love of the land and the people, and also decisively for his appreciating eyes. As an artist with his eyes set on the "present", his sustained effort in transcending the limits of socio-economic constraints will continue to be relevant. Especially in the age of digital reproducibility—when image seems outrageously ubiquitous, yet utterly devoid of meaning, Zainuls's proximity to the natural rhythm of life serves as a way to revive the value and verve we once we associated with painted image. The indomitable spirit with which Zainul approached both art, education and life still seems infectious after all these years. Even amidst the chaos of media exploitation and political parochialism, he stands tall amongst all people. He breathed his last on May 28, 1976.

1. Abul Mansur, Zainul Abedin, the main essay in the book Zainul Abedin, from the series Great Masetrs of Bangladesh, published by Bengal Foundation, 2012, p. 26.

2. Ibid, p. 24.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist, writer and art critic.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments