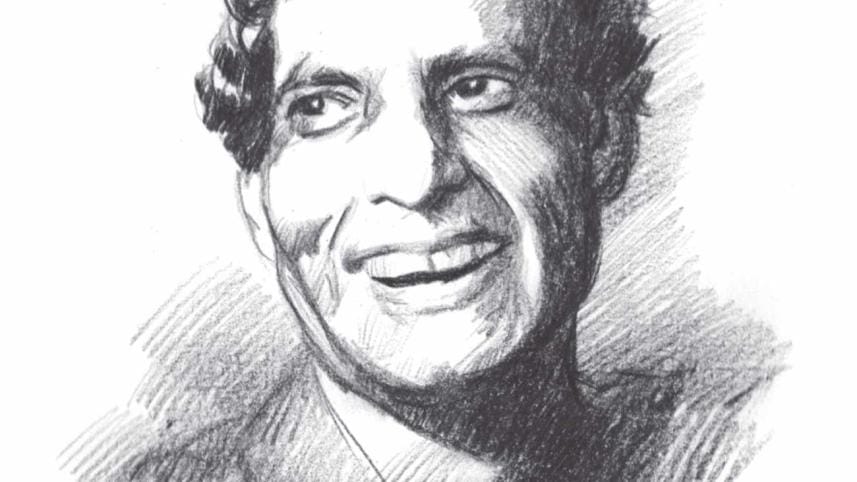

Ahmed Sofa In Posterity - Muslim Anxiety In A 'Muslim World'

We begin at a time after the battle of Karbala, where the traitor Simar is carrying Hazrat Hossain's disembodied head to Damascus in the hopes of getting a sizeable bounty. The story goes that he stops midway to rest for the night at a Brahmin family's homestead. Night comes and Simar falls soundly asleep. That night, by some miracle, Hazrat Hossain's head speaks and out of his mouth comes the Qalima, and the Brahmin, his wife, his seven sons and their wives all convert to Islam that very night. The legendary story, canonised by Mir Mosharraf Hossain in his work Bishad Shindhu, is actually a very old Islamic punthi (lore/story) which proliferated all across Bengal and beyond as Islam staked a place in the social order of the subcontinent, and in the hearts of Muslim ryots (peasants).

This is where Ahmed Sofa, too, begins his seminal work Bangali Musolmaaner Mon (The Psyche of Bengali Muslims). What, he asks, were a Brahmin family doing in the middle of the desert in the Arab world? Literally any other character (Jew, Christian, Zoroastrian) would make for a more plausible story. But the story speaks of a Brahmin and it says more about the Muslim psyche of this region than any factual narration of events. It speaks, according to Sofa, directly to the anxiety that people inhabiting this region, namely Bengali Muslims, carried with them at that time. And it offers a miracle, a salvation and a literary victory over the caste that had historically ruled over them for centuries (for even during Mughal rule, historical documents suggest that the core of East Bengal zamindari remained to a large extent under the control of the Brahmin upper caste, who were a big ally to the Mughal empire's nexus of rent-seeking and taxation).

Sofa identified correctly, as did Bhashani before him, that complex and multifaceted expressions of Islam were intrinsically linked to the historical identity of the millions of deprived and oppressed people of this part of Bengal. While there is much debate about Islam's role in the subcontinent, be it as a religion of salvation from caste-based violence, or a tool for Mughal political expansion, there is little doubt that Islamic punthi from that time painted itself very much to be the former. From Hazrat Ali to Muhammad Hanifa to Amir Hamza, all these characters performed heroic and miraculous deeds which invariably ended with the conversion of Brahmin characters to Islam.

Over the course of the centuries, Islam has played a crucial and complex role in shaping the identity of the millions of Bangladesh. Through many historic ruptures and solidification of ideologies, the Islam that we encounter in our daily lives and in discourse around us today, is a much-transformed version of the one which gave voice to the punthi writers of yesteryears. However, there are still strands that connect the past to present-day Islam and its struggle for state-making and un-making. Today, we encounter a nation beset by militancy, crippled with an anxiety of 'exported fundamentalism' that has nightmares of suicide bombings and assassinations, that reports lost boys in Panjabis at the Book Fair to the police and that sees its Hindu population shrink steadily every day.

The urban bourgeoisie and its armchair intelligentsia has attempted to devise its own explanations in recent times, all of which appear as historically and contextually divorced from reality as their own culture—bad parenting, social media, bad peer groups, radical Imams and so on. In an essay published in 1992 titled 'On the Issue of Bangladesh's Upper Class and a Social Revolution', Sofa made the point that the nexus of urban elites had zero ties with the large swathes of poor and struggling people across the country. “They are more foreign here than foreigners themselves… they identify and aspire towards a global cultural existence which has no roots in the realities of the millions in this country”. That was then. In the twenty-five years since then, what has happened to this 'bourgeoning' gap? The chasms have grown wider even as the proliferation of technological apparatuses like social media and the internet bring a virtual proximity to the lived experiences of the people of this country. In short, it has become much, much easier to virtually experience these differences in culture and lifestyles and add to the anxieties accumulating on both sides of the cultural and economic divide.

Today, we can learn from Sofa, who said very long ago, in an essay published in 1998, that the basis of the religious/secular dichotomy that grew prominent between the Islamic fundamentalists and the communists of his time, was a cause for great concern. He held on to the belief that much of Bangladesh's Muslim population were not fundamental at all, but that without a concerted effort for dialogue, these dichotomies bore the seeds for fascism. This dichotomy, which has staked a prominent space in modern day Bangladesh, is the historical expression of a century long nation-making process that defined borders and the bodies that are tolerated in those borders.

In the subcontinent's clientelist political set-up, is it possible to amass large congregations on an ideology alone? To think so would be to deny history its place in the formation of Islam in the subcontinent. This fascist tide has been decades in the making and it stems not from some inherently Islamic ideology, but from the expressly state-capturing agenda of an internationally backed Muslim class, who have been able to exploit the vacuums created from the continued economic and political deprivation of the majority of Bengali Muslims in Muslim majority Bangladesh. These extremist institutions have large terrorist networks funding attacks across the world, and it complements the nexus of Wahhabi money which infiltrates and colonises expressions of Islam across the world. Mass mobilisation, like we saw in Motijheel in 2013, can be, and is, co-opted by the very aforementioned fascist forces, but they feed on very real socio-economic anxieties of the protesters. At a time when it is easier to believe that the very fabric of their social space is altering beyond their control, the easiest place to turn to is towards the fascists. And we experience that fascist fervour in full flight today, from the gatherings in Shapla Chattar by Hefajat-e-Islam to the houses burning in Brahmanbaria. And fascists only rise in places where the state has failed.

In a way, the continued violence against the Hindu population of Bangladesh juxtaposes itself today next to the anxieties of old. The burning fascist tide, symbolized by the throngs of men and boys dressed in panjabis, has become the unwitting ally of the land-grabbing, patrimonial elite who have themselves deprived the masses from just economic and political representation, and have invoked the bitter histories that have been etched into subcontinental bodies since the days of Partition.

The Fascist Affect

The Wahhabis staked their place in the subcontinent's history first through Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi and his teachings, and it gave rise to a large nexus of connected Islamist movements in the subcontinent of which Titumir's battle with the British remains the most iconic in Bengal. The slow spread of Wahhabism also led to the establishment of a school in Deoband, whose branches slowly proliferated all across the subcontinent. Qawmi madrasas, away from the control of the government, act as institutions of Wahhabi/Barelvi philosophy and ideology. In his 1998 essay, Sofa speaks of a Hujur from the Deobandi school who was descended from the offshoots of the Khilafat movement, which garnered so much bipartisan support from Muslims and Indian nationalists alike. This person won three times as many votes as JASAD's Major Jalil, despite there being a much robust political framework and popularity on JASAD's side. This result surprised Sofa, so much so that he decided to befriend the Hujur and his murids to know the answer to this.

While not explicit, Sofa's texts can be read as hinting towards potential anxieties. Islam has played a historically crucial role in the expression of the anxieties of the population of this country. Where pre-colonial and colonial era anxieties led to liberatory forms of expression, today's anxieties have created the space for fascist ideologies and institutions to embed themselves into the social fabric of Bangladesh, which in turn have aligned the body towards an external violence. In his essay, Sofa spoke most of initiating dialogue, so as to bring political engagement to the table. Where the communists could sit at the same table as secularists and the religiously inclined and where the participants could, as members of a democracy, debate about the future of a country in which they all had a stake. Posterity shows that these collaborations have not materialized. A politics of power has, by and large, removed any hope of a politics of participation. Foreign interests, capitalist accumulation and continued censoring of dissent has driven this chasm wider and wider and the space for a fascist force, which comes today in the form of groups like Hefajat-e-Islam, is now ripe. True to its character, the government has chosen to pander superficially to these groups to maintain its own grip on power, without truly addressing the anxieties from which these forms of dissent are born.

I want to end, again, at the 1998 essay by Sofa. In it he spoke of a madrasa opening at Kamrangir Chor, which wanted to develop a new curriculum and way of teaching. At its opening Sofa was invited to speak and, later on, he had this to say about it: 'My joy stems from the fact that the Maulana did not seize the mic from my hands and kick me out of the ceremony. Instead, he chose to attentively listen to my unpleasant speech for an hour. I am certain that this is the beginning of social change… If one madrasa can begin this instance of dialogue, surely others cannot remain in their positions for too long'. While Sofa's hopes may not have fully materialised, it shows us that dialogic collaboration is very much possible and, in fact, necessary to stem fascist tides and begin a journey towards a participatory democracy. Any politics that claims to speak for the people must then undertake this long and painful journey of dialogue to identify the ways in which ruling class and bourgeois politics has itself created the grounds from which this terrifying violence emanates.

The writer is a research fellow at Center for Bangladesh Studies (CBS).

References:

Kamrangir Chor e Madrasay Shikkha Biplober Shuchona, 1998

Bangladesher Uchubitto Sreni Ebong Somaj Biplob Proshongo, 1992

Bangali Musolmaaner Mon, 1981

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments