Together in Tagore’s imagined world

"Who am I? "

This was a question asked by Tagore in his poem, "Prothom Diner Shurjo" (The First Day's Sun) written during his last days. Aruna Chakravarti, an eminent writer and academic, rebuilds the poem not just with translation but with the joie de vivre of an artiste creating a theatrical scene, wrenching out the poignancy of the departure of a great soul and the end of an era. Only she does it with words in her historical novel, Daughters of Jorasanko (HarperCollins India, 2016). She tells us how the poet called his granddaughter, Nandita, to jot down his last poem on July 30, 1941. He was too sick to write himself as reflected in the academic works that cluster around Tagore's lifetime. Chakravarti says most of her novels are fiction, with roots deeply embedded in factual research. She recreates, rebuilds the characters in keeping with the times and the era he lived in. The effect is immersive.

What made Tagore into the giant he was—writing, feeling and acting to bridge gaps to create a new world with his vision—is well brought out in the Jorasanko novels. The two novels map Tagore's journey from birth to death, giving the reader a comprehensive view of his times, the changes the world went through and a smattering of major historic events that affected the Asian subcontinent.

Tagore's last days have also been recorded by Somdatta Mandal in her more academic-based The Last Days of Rabindranath Tagore in Memoirs (Birutjatio Sahitya Sammiloni, 2021), gleaned from the writings of the many women around him, women who became big names in their own lives. Perhaps, being in touch with a soul like Tagore, changed them in ways more than one. This has been corroborated by Mahasweta Devi (1926- 2016), who won a Magsaysay Award for her "compassionate crusade through art and activism to claim for tribal peoples a just and honourable place in India's national life". In Mahasweta Devi: Our Santiniketan (Seagull Books, 2022), recently translated by Radha Chakravarty, the author mentions how she was impacted as the students mingled with Adivasis during festivals and how the older children from Santiniketan would go to the village of Surul, where Tagore had set up Sriniketan in 1922. Uma Das Gupta tells us in her book based on decades of research, A History of Sriniketan: Tagore's Pioneering Work in Rural Reconstruction (Niyogi Books Pvt Ltd, 2022), that Tagore considered Sriniketan as his 'life's work'. Mahasweta Devi writes how Tagore had a conglomerate vision where he wanted the literate middle class to bridge borders between villagers and the city folk, the uneducated and the educated, often corroborated by sentiments expressed in his own writings. Das Gupta refers to the maestro's poem "Ebar Phirao More" (Now Take Me Back) where the maestro writes:

Poet, come forward—if you have only life,

Then get that with you and dedicate that today.

With immense pain, sorrow, the deprived

Suffer hardships, weakness, death and darkness.

They need food to live, light to find the breeze of freedom.

They need strength, health, a bright happy future,

Courage, guts. Amidst this poverty, O poet,

Inspire a vision of trust that creates a heaven.

(Excerpted from the translation of "Ebar Phirao More" from Borderless Journal)

What made Tagore into the giant he was—writing, feeling and acting to bridge gaps to create a new world with his vision—is well brought out in the Jorasanko novels. The two novels map Tagore's journey from birth to death, giving the reader a comprehensive view of his times, the changes the world went through and a smattering of major historic events that affected the Asian subcontinent. The movement out of oborodh or purdah is mapped in Jorasanko (HarperCollins, 2013) along with the start of the modern woman as visualised by Tagore, the start of Santiniketan with the support of his wife who dies at the end of the novel, and of the strengthening of Brahmoism under Debendranath, Tagore's father. In Daughters of Jorasanko, Chakravarti has brought into play characters like Swami Vivekananda and Margaret Noble to give authenticity to the era. She has brought into focus Tagore's son's and family's involvement with Sriniketan. Some of the events mapped in this novel include a visualisation of his response to the first partition of Bengal in 1905. She expresses the outrage felt by Bengalis united by culture. "Bengalis were waking up to a sense of nationhood and they were coming together through their language and literature." She moves on to describe the historical events: "The news of the impending partition was followed by indignant meetings and rallies aimed at stalling the move. Rabindranath, the leading poet and composer of Bengal, voiced his protest through a number of soul stirring lyrics. 'Amar Shonar Bangla', he wrote one night on a visit to the family estate in Shilaidaha, 'ami tomai bhalo bashi' (My Golden Bengal/ I love you)'. This song captured the public imagination so powerfully it became an anthem for the movement and was sung at all the assemblies."

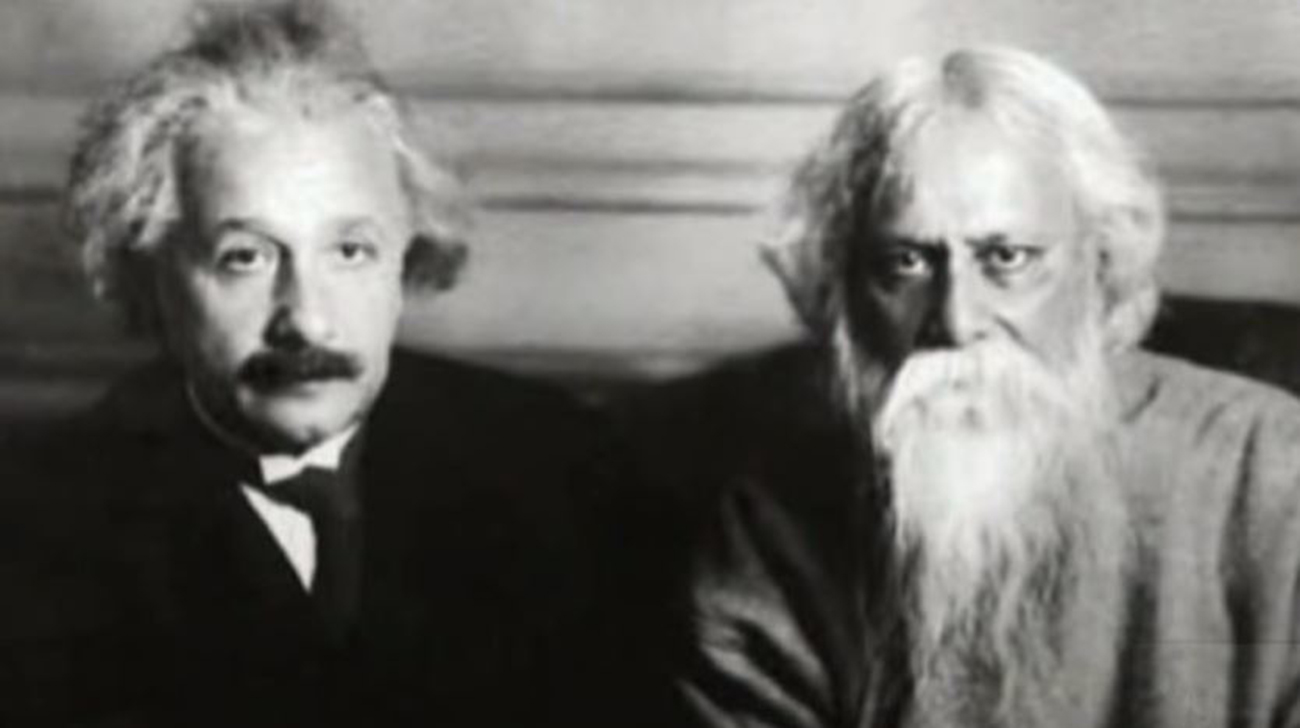

Later, she describes Tagore's rejection of knighthood after the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre (1919)–far from Bengal but still a matter of great perturbation to his genius as he believed in a united world. Tagore's reaction and the Western world's dismay over this act of his has been discussed in the podcast, Empire, by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand. Some of the social implications, like girls marrying later, mixed marriages, and women involved in changes outside their homes, the breaking of taboos, like those associated with overseas travel, are sprinkled through both the novels.

The last chapter of Daughters of Jorasanko describing Tagore's death and its aftermath is not just relevant but also a powerful comment on the way the world has treated Tagore's ideology and vision. Chakravarti visualises this conversation before his death in Jorasanko:

"'Why do you talk of death?' Rathindranath felt a ball of lead thump slowly against his chest. 'You're not dying.'

"'I don't want to be carried in a procession to Neemtala,' Rabindranath continued as though he hadn't been interrupted, 'with shouts of Rabindranather jai bursting my eardrums. I want a quiet cremation by the banks of the Kopai river. And my ashes ... I want my ashes to be strewn over the khowai.' He paused for a few moments and added, 'But before that, place my body on the ground in the shade of the chhatim tree where, nearly a century ago, my father meditated and found peace.'"

But when he died, his wishes were as disregarded as history has shown his hope for a united Bengal or even his desire to bridge gaps and social distances. His corpse was carried in a procession that rang with the chants of "Rabindranather jai" as Rathindranath weakly protested about the need to respect his father's wishes. With this single stroke, Aruna Chakravarti highlights how society creates icons, disregarding the vision or values cherished by the man behind the image, leaving us wondering if fame is at all desirable.

History and civilisation with its divisive constructs seem to have continued to disregard the dreams of the polymath, who, as Nigel Hughes, a professor of geology who had spent some years in Santiniketan, contended, was more than just a poet, a writer, an artist and philosopher. Hughes comments: "Were Rabindranath not so famous for his other accomplishments, his role as an internationally important practitioner in comprehensive rural developmental work would be more widely assured and appreciated." Maybe, we can only imagine, imagine a world woven out of the fabric of Tagore's writings, dreams and actions.

Mitali Chakravarty writes and edits for peace, love and harmony. In that spirit, she has founded an online journal, borderlessjournal.com, which has recently brought out its first anthology edited by Mitali, Monalisa No Longer Smiles: An Anthology of Writings from Across the World.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments