In some corner of a foreign field: Rahmat Ali & the once and future Cambridge Majlis

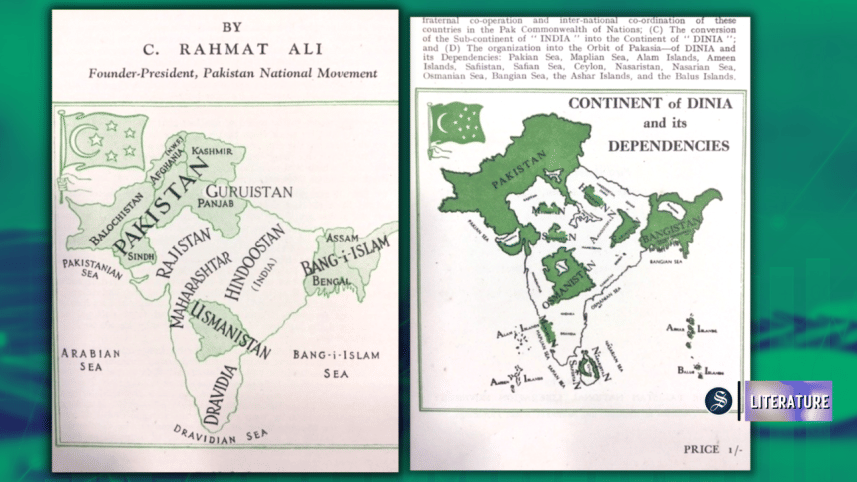

What year would you say modern Bangladesh was first conceived of as a separate nation? I ask the question because I have just been looking at a map of South Asia adorning the cover of a pamphlet published in Cambridge in 1933 and, there it is, large as the leaf if not life, Bang-i-Islam.

The map is part of an exhibition arranged to mark the revival of the Cambridge Majlis, a society (dating from 1891) designed for students from all over the Subcontinent to meet socially to enjoy their commonalities and discuss and debate in a civil way their political differences.

The map has some historical interest. The author of the pamphlet, Choudhary Rahmat Ali, is remembered as the person who first coined the name 'Pakistan'. This attribution is now contested but what the pamphlet, "What Does the Pakistan National Movement Stand For?"–and a succession of others that followed in the 1930s–shows is that he was the first and most vociferous champion of the existence of Pakistan as a separate nation (and not just region).

History has its ironies. What has been conveniently forgotten is that Rahmat Ali was the first to renounce the name of Pakistan as it came into existence at the time of Partition. So disenchanted was he by the Pakistan he encountered in reality compared to his ideal conception of it in Cambridge that his own return there in 1948 lasted barely six months. He was actually expelled, dying so poor in Cambridge several years later that his college had to pay for his burial.

Rahmat Ali's view of what he called South Asia (a term that has now come into general use) was that there was no such entity as India, only a number of coherent communities that should form separate nations in a continent he called Dinia (an anagram designed to highlight its diversity of religions). While the term "All-India" he denounced as a trap has proved as resilient as he feared it might in the face of centrifugal forces, his 1933 map remains intriguing.

As the map shows, there were to be eight nations: besides Pakistan, two other Muslim nations, a pan-Bengal Bang-i-Islam (including Assam) and Usmanistan (covering Hyderabad), plus a Sikh Guruistan, Hindoostan, Rajistan, Maharashtar, and a Dravidia.

Drawing up maps of the Subcontinent and inventing new names for places on it was not an eccentric pastime. The Majlis in Cambridge existed precisely to argue for and about the imminent freedom and re-arrangement of the Subcontinent. Rahmat Ali's pamphlet was in response to discussions at the Round Table Conferences.

Rahmat Ali continued to hone his conception of a multinational South Asia. A more elaborate map used to adorn the covers of further pamphlets refines his notional nations–and their names–to take in, for example, an Akhootistan (his preferred term for an Untouchable homeland based on an Arabic root) and some ten Muslim homelands in South Asia, including two in Sri Lanka alone, Safiistan and Nasaristan.

Neither of the two other major Islamic nations, Usmanistan (later Osmanistan) or Bang-i-Islam (later Bangistan), came into existence to the extent he had imagined them any more than did his Pakistan (renamed Pastan to distinguish it from the "Quisling-i-Azam" Jinnah's truncated state). The Nizam failed in his attempt to establish Hyderabad as a separate nation in 1948 while East Pakistan encompassed neither West Bengal nor (barring Sylhet) Assam.

Rahmat Ali's conception of distinctly separate and equal nations did allow him to be clear-sighted about the relationship between the (then existent) two wings of Pakistan. In his pamphlet Pakistan or Pastan (1950), a critical attack on the home and foreign policies of Pakistan, he argues against their forced integration into one country.

One thousand miles distant, divided from each other by hostile territory, a capital humiliatingly far away for one, with its peoples having radically different life-styles and a history and geography dictating that they look in a totally different directions, these separate nations could be united only by freely associating–as he had always advocated–in a commonwealth of equals.

One interesting additional observation, given how totally Rahmat Ali deplored caste Hinduism and its commitment to capitalism, was that he thought it politic for the caste Hindus of Bangistan to be involved in the Government of this Bengali Muslim nation.

Manifestly, Rahmat Ali's conceptions are heavily weighted towards Islam. Equally problematic, once you advocate the balkanization of South Asia with its intermixture of populations, is that there is no end–as maps of today's northern Bangladesh show–to homelands that proliferate into enclaves and then enclaves within enclaves.

Other members of the Cambridge Majlis had quite other ideas to Rahmat Ali's, most usually secular and socialist. Over the years, the Majlis had a roll-call of members, let alone guest speakers, who provided much of the intellectual leaven for the independence movements of all the nations of South Asia, including (the then) Ceylon.

While Muhammad Iqbal stands out as an eminence gris behind Rahmat Ali, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sri Aurobindo and Subhas Chandra Bose, among others, were active members who had other maps in mind. The novelist Mulk Raj Anand, who attended meetings regularly, though as affronted as Rahmat Ali by caste oppression, addressed it quite differently by writing his novels Untouchable (1935) and Coolie (1936).

The discussions and debates of the Majlis attracted the attention of Scotland Yard since, though members were usually well-off, guest speakers were frequently progressive and left-wing, including prominent Communists such as Ben Bradley, one of the accused in the seminal Meerut Conspiracy Case (1929-33).

The Majlis was invariably outward-looking, especially in the 1930s, raising money in support of the Spanish Republic during the Civil War and for Chinese Students during the Japanese invasion. In turn it received a donation from the Indian-Irish Independence League, "Yeats's" Maud Gonne then presiding.

The Majlis was not all serious politics: dancing and music kept breaking in. One note reports that Mr Milia from the sister Oxford Majlis sang with great force in Bengali and Mr Mm. Qizilbash delighted the House with a Pashtoo song in which several members joined.

One guest who spoke to the Majlis–on the occasion of the murder of Mahatma Gandhi–was E. M. Forster. 20 years earlier he had written his seminal novel on India, wrestling in a rather more philosophical way than Rahmat Ali with the question of whether "India", like the world, was One or many.

Other members of the Cambridge Majlis acted as midwives to the Bangladesh that 20 years after Rahmat Ali's death was born like a phoenix out of the ashes of his "battered Bangistan". It was while recruiting for the Majlis that Rehman Sobhan met his wife-to-be, Salma Ikramullah. Rehman would be one of the drafters of the Six-point programme for Bangladesh Independence, Salma a human rights activist who founded the Ain-o-Shalesh Kendra.

The story of their meeting is related by fellow Majlis member, Amartya Sen, someone who surely embodies the eclectic, harmonious spirit of the society with his concern for economic justice not only in both Bengals but the wider world. Rehman referred to Amartya as their "opening batsmen '' in debates such as those they had in Oxford with Kamal Hussain, later to be the presiding spirit of the Bangladesh Constitution and much else.

The influence of both Oxbridge Majlis gradually dwindled after the Liberation War of 1971. Happily, shortly before Covid struck, students from the Subcontinent decided it was high time once again to encourage their fellows to consider the commonalities they often discover they have as they study in some corner of a (by now) not-so-foreign field.

The topic of the first debate after the Majlis revival in Cambridge was "that this House regrets the 1971 Indo-Pak War". However controversial the opinions aired and shared on that motion, when the pandemic struck, by common consent funds were raised to support the fight against Covid equally in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

No doubt, as the current Majlis aspires to discuss ways to better the world, there will again be, as there were ninety years ago, informers and infiltrators acting for government organizations hostile to the workable relationships so desperately needed to further the progress of the Subcontinent. May these stooges be as successful as Scotland Yard was in preventing Independence.

As for outlier Rahmat Ali, has he been altogether forgotten? Apparently not. From time to time a Pakistan flag is placed on his grave in Cambridge - and is just as often removed. Could it be that his own ghost is responsible for its removal?

His ghost certainly haunts the little box that contains his other – intellectual – remains, his twenty or so polemical pamphlets. To the irritation of those who would like to keep him securely inside, these show him, like any good intellectual, thinking outside the box.

John Drew is an occasional contributor to The Daily Star. A collection of his articles is due to be published later this year by ULAB Press.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments