Kazi Nazrul Islam’s short narratives

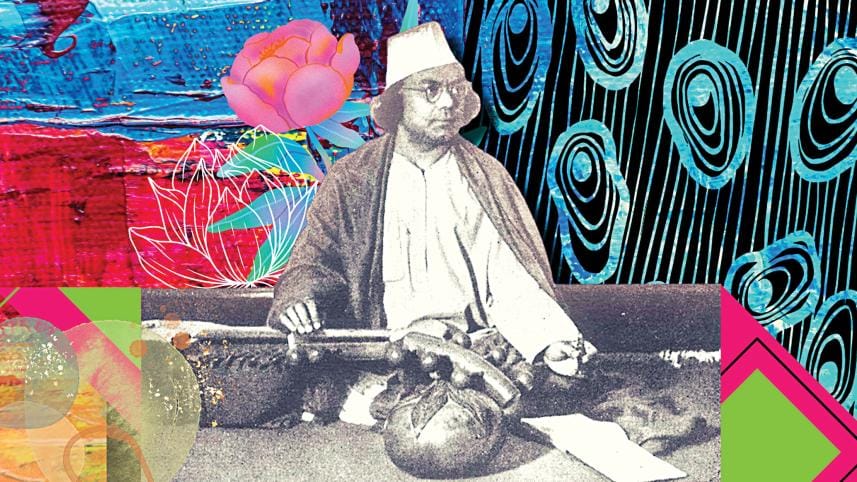

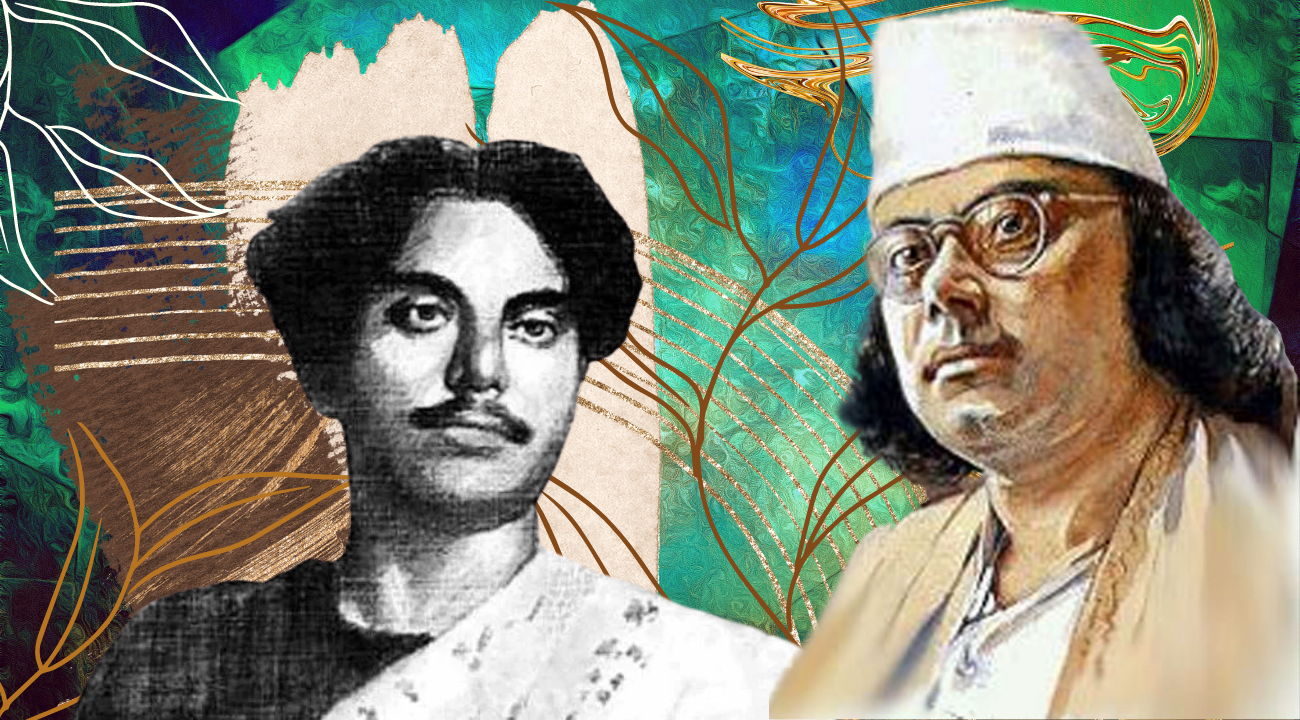

Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), was a poet, novelist, lyricist and musician in Bengali, and was popularly known as the rebel poet. He seemed to appear out of nowhere upon the Bengali literary scene, much like the comet he has often been compared to, drawing from the name of his first literary journal Dhumketu. Famous for his anti-colonial poems and lyrics that preached communal harmony during the period of the late-colonial era between the two world wars, he also wrote a substantial body of prose that encompassed reportage, journalism, fiction, political thinking, and literary essays. Feted by all three countries that were created out of the Indian subcontinent, he is considered to be the national poet of Bangladesh.

While Nazrul Islam's poems, songs–and more recently–his novels, have been diffused into global cultures through English translation, his short narratives have not received the same treatment yet. His prose–in the form of speeches, essays, novels, polemics and stories–is a crucial part of his evolving body of work. His early stories were written to document and narrate his experiences of war, based on his time with the 49th Bengal Regiment that was barracked in Karachi (and briefly, Nowshera) during the First World War. Even though the regiment did not see much action, Nazrul's stories are fantasies of bravery, masculine courage and youthful experiences of love and ambivalence about national causes. He was fulfilling several roles at once: displaying martial prowess among the 'bhadrolok' Bengalis, who were largely thought to be too genteel to be in the army according to colonial stereotypes; emphasising the presence of Muslim youth among the Bengalis who fought for the empire, and later against it, creating a fantasy-tinged narrative of romantic engagement against the background of global conflict. Soldiers in Nazrul's stories fight on behalf of the colonial empire, for central Asian freedom struggles as well as the Red Army in Russia. Even though the First World War is rarely name-checked in his poetry afterwards, as scholars like Santanu Das have pointed out, "(t)he influence of the war years can be detected not only in a few explicit 'war' writings, but in a more general sense, from his greater confidence to his self-fashioning as a sainik (soldier) to infusing Bengali poetry with martial images and rhythms it had not known before". There is a line of continuity between Nazrul's narratives and his poetry and song, with each genre providing their unique set of affective frames that could serve Nazrul's effort to express his formative identity. And violence was often central to this act of forging one's identity in a late-colonial context, as much for Nazrul as for many European writers and artists who thought of global wars as technological means for securing idealistic futures; Das suggests the same when he writes that "the war opened up for the tempestuous youth and avant-garde artist a rich imaginative space, replete at once with desire and violence, with violence as desire". These conflicted, almost contradictory, fantasies tell us many things about how contested the world of imagination was in late-colonial Bengal, especially when it came to formulating political programmes for struggle–either against the colonial government or the emergent, 'nationalist' middle-class society at large (traditionally understood to be the object of reform).

These stories offer a glimpse into the life and mind of Nazrul at a young age before he took Kolkata and Bengal by storm with his rousing songs and poetry. They are witnesses to his struggles with himself in the domain of ideas and love. They help us appreciate the great rebel poet more by giving us unrestricted access to his fears and obsessions as a detached, carefree vagabond who sought learning and experience from the world- all by himself and through his narratives. We see glimpses of this soldier-cum-vagabond lifestyle described in his novel, Bandhon Hara (Unfettered), which has been translated into English, but the shorter narratives collect various aspects of this existence imagined through different combinations and romantic possibilities, each signifying a distinct emotional core in Nazrul's poetics. These stories will help English readers to place Nazrul in an intellectual and social context of his own making and historicise his exuberant creative work. They are drawn from his three major collections of short stories: Byathar Daan (The Gift of Pain), Rikter Bedon (The Feeling of Emptiness), and Shiulimala (The Garland of Sorrow).

Even within the small category of Bengali writers writing about the time of the First World War, Nazrul's stories stand out for their unique and unstable mixture of violence, fantasy and romance—threatening to unwork any narrative coherence or claims of 'realism' in stories like Hena or Byathar Dan. These may be described explicitly as stories of a young Bengali experiencing the world of war at the same time as working out various ideological conflicts within the self, with an emphasis on war's romantic possibilities. Even if the stories read fantastically, very often they reflect the thick atmosphere of grisly rumours of violence, betrayals and ideological border-crossings that took place at the time, which also opened up opportunities for alternative self-making, compared to what inspiration was available before that in a colonised state. According to Abhishek Sarkar, "Nazrul was also aware…that some Indian soldiers in Iran had mutinied and deserted the British army to join the Red Army. Among them one Murtaza Ali excelled in guerrilla warfare in the northern Caucasus, and probably served as a prototype for the heroic character named Dara in Nazrul's story Byathar Dan. Nazrul encapsulates in the figure of Dara his favourite ideals of internationalism and heroic masculinity, of which he could not find any embodiment in his lived experience as a Bengali." Ultimately, through the telling of great world events like the War, the stories will find universal interest as part of a growing archive of war narratives from colonial soldiers and participants who were never directly implicated in the global conflict but by virtue of their forced membership in an imperial commonwealth. The coerced nature of this association is revealed through the cracks in Nazrul's portrait of his war protagonists and their febrile search for causes.

The other section of the collection is built around narratives of the social world of Bengali villages and small towns during the early 20th century. They give us glimpses of historically-rooted social experience–of Muslims and Hindus living together during the times of the Non-Cooperation Movement, for instance–marked, once again, with elements of fantasy. These stories are imagined in the literary context of earlier puthi narratives as well, and are probably better thought of as afsanas or tales, where temporal events are suffused with the imaginary world of ghosts, jinns and sentient serpents. In "Jiner Badsha", the female protagonist is named Chan Bhanu after a popular character from a qissa that is much admired by her mother, while the male protagonist whiles his time away reading tales of Shonabhan bibi and imagines himself to be the new Gazi Hanifa. These popular tales and outsized fantasies intrude upon the everyday world of the Bengali rural idyll, grafting insidious desires for romance and adventure, and making it possible for us to trace the characters' motivations and self-fashioning in the domain of this particular social imaginary.

Nazrul narrates these tales with his tongue in his cheek, reflecting the larger context of secular and conservative political debates that were waged around the need for rationalist methods in approaching faith-based communities that were in dire need of 'modernisation'. The translation also includes two short allegorical narratives by Fazlul Haq, Bengal's first Prime Minister and friend of Nazrul, that were reproduced by Nazrul in the journal, Nobojug. These emphasise the comedic aspects of Nazrul's work–whereas he is traditionally known for his angry, rebellious lyrics, or lachrymose devotionals (to the goddess Kali, for instance). Comedic narratives and the use of fantastic elements allowed Nazrul to create popular forms, re-tell older stories and communally-shared oral narratives, which let him evolve an important dimension of his aesthetic. Although for Nazrul–even in the midst of laughter, we are still talking about politics, and the struggle waged by the emotional, individual self against the socially structured, increasingly rationalised and enumerated world of late-colonial Bengal.

Ankan Kazi is a writer and translator. His essays and translations have appeared in the Sahitya Akademi's Indian Literature journal, Jamini, DAG Journal, Caravan Magazine and The Wire, among others. He is also the great-grandson of Kazi Nazrul Islam. He works as a researcher in Kolkata.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments