Intuitions of Harmony: The Vibrant Vision of Rabindranath Tagore

Ever since the COVID pandemic began, 'distance' and 'isolation' have become catchwords in our code for survival, but these words also assume a wider resonance in geopolitical terms, for today we inhabit a world that is increasingly riven by social, economic, religious and political fissures. At this moment, it is worth reflecting on the broad, inclusive vision of Rabindranath Tagore, whose words conjure up a diverse yet interconnected universe, where all things, great and small share an underlying unity: "The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures" (Gitanjali).

Born in 1861, Rabindranath was brought up in a large family with an open, eclectic approach to culture, religion and the world of ideas. This receptivity to heterogeneous influences remained with him throughout his life, expressing itself in his thought, writings and practices

As a humanist, Rabindranath believed in reaching out beyond the comfort zone of home, to seek out the unknown and unfamiliar. A compulsive globe trotter, he travelled across continents, to connect with people and cultures in different parts of the world. In fact, he came to be regarded as a mediator between nations, almost a prophet and mystic, and India's international cultural ambassador. Contact with diverse cultures widened his horizons, and sensitized him to the importance of embracing otherness:

Thou hast made me known to friends whom I knew not. Thou hast

given me seats in homes not my own. Thou hast brought the

distant near and made a brother of the stranger. … (Gitanjali)

Exposure to other cultures also enhanced Rabindranath's nuanced understanding of East-West relations. Although he strongly opposed imperialism, even surrendering his knighthood in protest against the Jalianwallah Bagh massacre in 1919, he admired English literature, Western music, and other elements of European culture. "Let us be rid of all false pride and rejoice at any lamp being lit in any corner of the world, knowing that it is a part of the common illumination of our house," he writes (letter to C.F. Andrews, 1920). Rabindranath's desire was for "the co-operation of all peoples of the world," while respecting mutual differences.

In Rabindranath's vision, humanism represents a higher value than nationalism. All the same, he does not actually reject the idea of nationhood. Rather, he insists on a more nuanced understanding of what the term "nation" can imply. In "What is a Nation?" (1902) he describes the nation as a construct based on the collective memory, aspirations and will to action of an entire people. As an alternative to the Western nation state, he speaks of samaj or society, "a spontaneous self expression of man as a social being," where relations between people "are not mechanical and impersonal but based on love and cooperation" ("Society and State,"Swadeshi Samaj, 1904). Novels like Gora and The Home and the World demonstrate his evolving ideas on nationhood and identity. His songs became the national anthems of India and Bangladesh, and inspired the Sri Lanka anthem too.

What frequently troubles Rabindranath is the prescriptive, monolithic imagination behind many social, political and religious systems. He critiques the idea of "one nation" being imposed on the world by imperialist power.

What frequently troubles Rabindranath is the prescriptive, monolithic imagination behind many social, political and religious systems. He critiques the idea of "one nation" being imposed on the world by imperialist power. To H G Wells (June 1930), he complains: "The tendency in modern civilization is to make the world uniform. Calcutta, Bombay, Hong Kong, and other cities are more or less alike, wearing big masks which represent no country in particular." Seen in retrospect, these insights appear far-sighted, for they anticipate contemporary debates about the culturally homogenizing effects of globalization.

Rabindranath's writings also reveal his anguish at different forms of oppression prevalent in society, and a prophetic sense of the rising tide of resistance to come. His views on social issues, especially on women's empowerment, appear ahead of their time in many respects. Texts such as Chokher Bali, Gora, "Khata," Chitrangada and "The Wife's Letter" address questions of female desire, gender stereotypes, the predicament of widows, women's role in nation-building, their right to education and need to find a voice. "Nari" argues that women will usher in a new and better world. Issues of caste, untouchability, and women's access to religion take centre stage in Chandalika. During his soujourn at Silaidaha, the young Rabindranath had witnessed the plight of the rural population in Bengal, and developed an empathy for the downtrodden. We see this concern in Ghare Baire and "Dui Bigha Jami." "It is the poor who bear the responsibility of freeing a society that has been trampled upon by the wealthy," Rabindranath insists ((Samabayniti, c. 1928; translated by Fakrul Alam). In Stray Birds he predicts: "Man's history is waiting in patience for the triumph of the insulted man."

The song himsaye unmotto prithibi expresses Rabindranath's distress at the violence and hate he sees around him:

THE WORLD today is wild with the delirium of hatred,

the conflicts are cruel and unceasing in anguish,

crooked are its paths, tangled its bonds of greed. …

O Thou of boundless life,

save them, …

Let Love's lotus with its inexhaustible treasure of honey

open its petals in thy light.

(Poems, 1942)

Natir Puja draws on the Buddha's image to make a plea for religious tolerance and inclusivity. Gitanjali questions religious rituals and orthodoxies, recognizing a god who lives in people's hearts:

Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads! Whom dost

thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors

all shut? Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where

the pathmaker is breaking stones. He is with them in sun and in

shower, and his garment is covered with dust. Put off thy holy

mantle and even like him come down on the dusty soil!

Rabindranath's writings exude a vivid sense of oneness with the natural world. Chhinnapatrabali manifests his visceral ecological consciousness: "This earth, like someone I have loved long, through many births, remains ever-new to me; the two of us share a very deep and extensive acquaintance." The story "Bolai" depicts a special affinity between human and natural realms. Rabindranath's songs, poems and paintings are suffused with this love for nature. Today, as the world reels from the impact of global warming, his ideas acquire a special resonance.

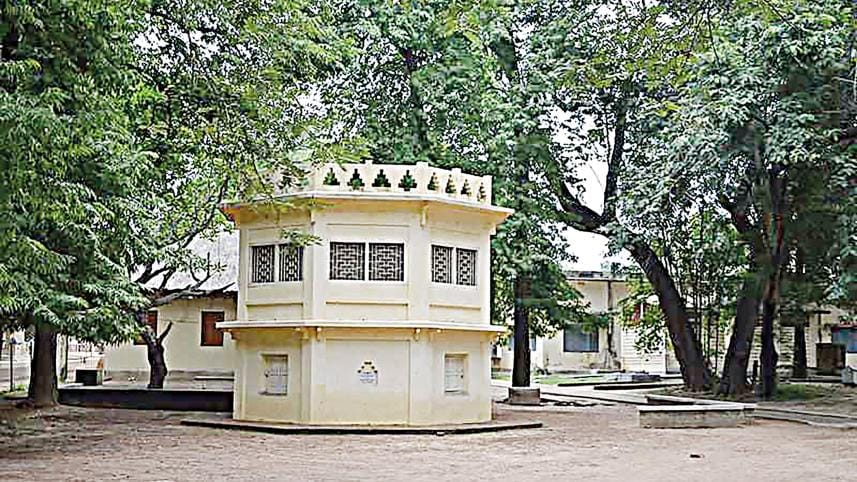

The educational experiments of Rabindranath Tagore also stem from this visionary dimension in his thought. As a school dropout unable to adjust to conventional methods of teaching, his own experiences fuelled his desire to invent an alternative system of education closer to nature and indigenous elements. In 1901 he founded a school in Santiniketan, in the heart of rural Bengal, where children would be taught in unrorthtodox ways intended to foster their intellectual curiosity, closeness to nature, creativity and self-reliance. Visva-Bharati, formally established in 1921, was a university inspired by Rabindranath's dream of bringing together "All the world in one nest" (yatra visvam bhavatyekanidam). The university was meant to draw together the finest elements from different cultures across the world, providing a space for dialogue across languages, intellectual systems and creative traditions. The idea was to develop the human personality as a whole, in order to promote the fullest possible realization of human potential. Rooted in local tradition yet truly international, Santiniketan aspired to combine modern science with spirituality. Sriniketan, the project for rural reconstruction that developed alongside, was designed to create social awareness among students while improving the living conditions of the underprivileged sections of the local community at Bolpur.

Rabindranath's often dystopian view of the world he saw around him paradoxically inspires his vibrant, inspirational imagination of a more harmonious existence. Perhaps it is time for us to revisit that dream:

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls …

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake. (Gitanjali)

Radha Chakravarty is a writer, critic and translator. She has co-edited The Essential Tagore with Fakrul Alam. Her recent translations include Our Santiniketan (Mahasweta Devi) and Char Adhyay (Rabindranath Tagore). She was Dean, International Affairs and Professor of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University, Delhi, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments