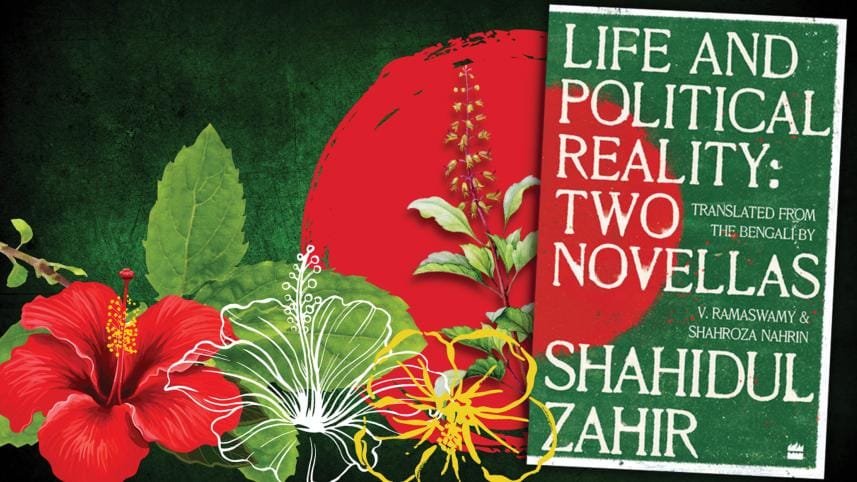

Genocide, ecology, and Zahir’s ‘Life and Political Reality’

As we remember the joys and the agonies brought forth by 16th December 1971, we often forget or, rather, neglect the nuances embedded in the struggle for liberation–nuances integral to both genocide and resistance. The nuance I speak of concerns the ecological aspect of war and genocide. Trees that grow on occupied land and are tied to the victims of oppression by an affinity that holds historical, religiocultural, or economic value, become both military targets and weapons of collective resistance. Shahidul Zahir's novella, Life and Political Reality (1988), narrates in a unique fashion the grimmer, underrepresented side of Bangladeshi independence. Wonderfully capturing the sense of a single collective consciousness during times of oppression, Zahir narrates the whole tale through its lens, which is enhanced by the unique narrative blend of traditional folklore and modern stream of consciousness. Here, the pivotal role of the tulsi and joba trees in facilitating collective Bangali resistance and, simultaneously, these trees' status as Pakistani military targets run parallel to the significance of olive trees for Palestinian people and their subsequent status as Israeli military targets. Together, these events testify to how genocide and ecological destruction go hand in hand.

"On a rainy day in the month of Shrabon in 1971, a rebellion had broken out in the moholla over the cutting of tulsi plants", narrates Zahir in the novella. Collaborator Moulana Bodu instructed a troop of "rajakars" to "cut down all the tulsi plants immediately" after realising that "the locality…was full of these plants." "They pulled out or cut from the base all the tulsi plants from every house, whether Hindu or Muslim" but "the matter became complicated when" they tried to pull out a joba plant in full bloom, bearing a hibiscus "red like blood", after they had surmised that it "was also a Hindu plant." The rajakar was unable to "break the tall and clustering joba plant from its base" and, as he kept trying, Momena, protagonist Abdul Mojid's soon-to-be-slaughtered sister "lost her self-control" at the sight and drove the unarmed rajakar out with a chopper to stop him from destroying the plant. Then, after he joined the other soldiers, "his wounded masculinity awakened" and he "incited his associates to cut all the flowering plants."

Momena's retaliation, however, is catalytic as it sparks collective resistance. The people of the locality subsequently get together against the rajakars and one person, seamlessly blending in with the collective such that he cannot be individually identified, lands "a mighty slap on the face of an isolated rajakar." Significantly, this female-initiated uprising shake the soldiers and Bodu becomes "agitated because he [senses] that underlying it all [is] the resurrection of courage in the moholla folk after it had been broken and crushed." Hearing of this, a Pakistani lieutenant asks "Kya aap aurat ko sambhaal nahi sakte? Can't you deal with a woman?" upon which Bodu becomes "extremely embarrassed." Banally, they "deal" with this woman by raping and killing her. But, Momena here reminds us of the unacknowledged female freedom fighters behind this country's liberation, who often met a more horrific end because of their sex. Both women and nature are marginalised and endowed with passivity in the discourse of war and liberation; however, this event in the story, where woman and nature together initiate collective resistance, highlights how they both are crucial agents of liberation.

As if in return for the protection provided by Momena, the tulsi plant protects the people of the moholla from a violent military operation, and the land protects Momena, albeit momentarily, from the rajakars. In retaliation for the uprising, the soldiers set out to conduct an operation that is thwarted when one of them "[comes] under the spell of the tulsi" as "his war-weary tongue instantly awaken[s] with the jolt of the sharp aromatic flavour." Subsequently, the rest of the soldiers, with "rifles on their shoulders and tulsi branches in their hands", are found chewing tulsi leaves which leads to the suspension of the military operation as Bodu, thinking they would all suffer from food poisoning, assumes that this "was perhaps a trap laid by the freedom fighters." Similarly, the land protects Momena when the rajakars arrives at her house but fails to find her because she lay "prostrate on the floor of a deserted…hut…her body was completely buried under ash and clay, and only three tubes of papaya-leaf stems connected her nostrils and mouth to the air outside." But merely six days before victory, "on the 10th of December, when aeroplanes were dropping bombs over Dhaka and the nation was waiting to be liberated at any moment" Momena was taken away by the rajakars, never to return; and thus, by underlining the cost of victory, this prevents the reader from celebrating victory day with zero conscience pricks.

The relationship of 1971 Bangalis to the trees of their land finds itself echoed in the significance of olive trees for Palestinians and their systematic destruction by Israeli forces. According to Haytham Dieck, "The olive tree in Palestine has essential economic, cultural, social, and national significance. It illustrates the Palestinian attachment to their land" because, like Momena's sturdy joba tree that the soldier fails to uproot, "olive trees resist the tough conditions of drought and poor soil conditions and remain attached to their place." They are a significant source of food and income for Palestinians. Not only have millions of them been destroyed by Israeli forces, but they have also been replaced by the non-native pine tree which Zionism has used to "serve its nationalist agenda at the expense of many, many Palestinian lives…histories" and "olive groves," writes Taya Amit. "The olive and the pine tree have thus become "planted flags in contested soil."

For instance, the Jewish National Fund (JNF), "disguised as an environmental NGO", "silently made the pine tree the quintessential symbol of Zionism." "With the purpose of buying, and taking, Palestinian land, the JNF has planted over 240 million trees, most of which are pine. The celebrated forests planted by JNF are, in fact, tools for the disappearance of Palestinian villages. The Lord Sacks Forest, the South Africa Forest, the Carmel Forest Spa resort—all built on the ruins of Palestinian lives. The largest JNF forest in the Galilee, the Birya Forest, took the place of six villages, one of which was "Ayn Zaytun, Spring of Olives, a farming village which homed 1,000 people." In contrast to the commonly perceived apolitical status of nature, the JNF's actions prove "just how political a tree can be—transformed from a natural being into a soldier defending a settler state." It is in this perceived neutrality of nature "that the Zionist agenda has conveniently been able to hide its activities and silence the consequences."

Irus Braverman explores how "when we paint a picture of trees using the brushes of settler colonialism and identity, we see how politics and nature are intertwined…Understanding collective memory as both a response to a shared event, and part of creating the event itself, Palestinians and Israelis have found very different meanings within the tree: the collective memory of the Israeli pine enrooted, at the expense of the Palestinian olive uprooted."

To conclude, pivoting an analysis of the plight of 1971 Bengalis alongside that of Palestinians today around themes of ecology and genocide reveals how the eradication of a people are inseparable from ecological destruction and, conversely, how collective identity and resistance is tied to ecology. We see how trees are tied to the identity of a people: Moulana Bodu in Life and Political Reality snarls "Tulsi gacch Hindura puja kore, ei gachh Hindu gachh." Similarly, olive trees are central to Palestinian identity, and pine trees to Israeli identity. Evidently, trees are anything but neutral during war and colonisation–they become highly politicised as they are transformed into weapons of war, colonialism, genocide, or resistance. They come to symbolise the collective identities of those engaged in conflict and act as auxiliary soldiers engaged in a human war on a non-human realm. Further, on a larger scale, the explosions in Gaza have undoubtedly been accelerating climate change: genocide decimates both people and planet. Thus, as we celebrate our freedom this 16th of December, we cannot help but let our hearts drift off to the Palestinians still struggling for their freedom.

Momena is an occasional contributor to Star Books and Literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments