The Great Wall of China

The morning mist clung to the hills of northern China, softening the sharp lines of the mountains. Then, through the shifting veil, I saw it -- the Great Wall of China.

It wasn't just its scale that stole my breath; it was the weight of time. This winding monument on the mountain ridges stood for centuries, bearing witness to human ambition, struggle, and endurance.

For years, I had pictured this moment. In photographs, the Wall had always seemed remote -- a cold relic from another age. Yet here I was, touching its rough stones, standing in the shadow of ancient watchtowers. I felt small, but also strangely proud. Generations had laboured here to create one of history's greatest feats of engineering.

I was on an 11-day trip to China as a member of a Bangladesh delegation. With our days filled with official visits, meetings, and cultural exchanges, the Great Wall wasn't even on our itinerary.

Then, on our ninth day, we stumbled upon a famous Mao Zedong quote: "He who has never been to the Great Wall is not a true man."

That was all the encouragement we needed. I voiced my wish to visit the Wall, and soon other delegates joined in. We went to our delegation head, Prof Rakibul Hoque, and Michael Zhu, asking if they could adjust the schedule, even if it meant cutting smaller stops. They saw our excitement and agreed.

On our last day, at exactly 7:00am, we boarded a bus for the 90-minute journey to the Mutianyu section of the Wall. Soon, Beijing's busy streets gave way to rolling green hills. At the main gate, a shuttle bus operated by the Wall authorities carried us to the mountain's base. From there, our ascent began with a cable car ride.

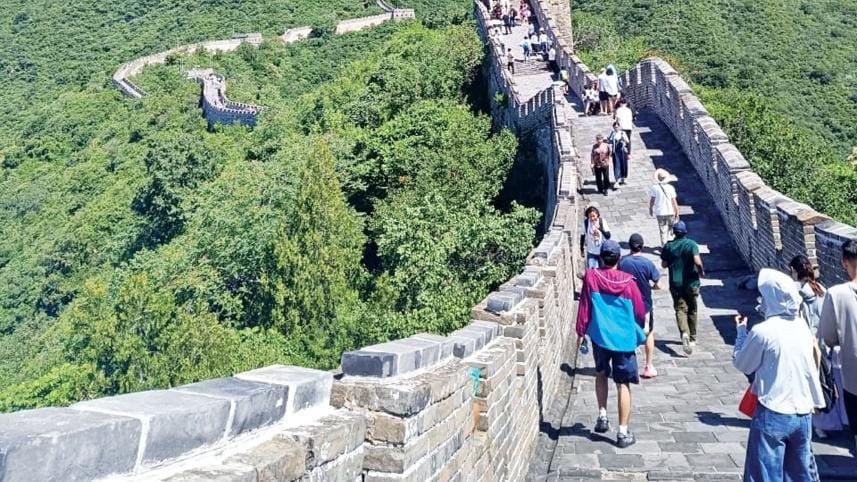

The Wall appeared and vanished through the trees as we glided upwards. Beside me was my closest companion on this trip, fellow delegate Saif Sujan. Together, we stepped off the cable car and onto the Wall.

We had only a little time to explore, and the Wall was huge. Sujan bhai and I decided to make the most of it. We walked quickly and sometimes even jogged along the stone steps and steep slopes, determined to reach the highest point open to visitors.

The climb was demanding. The steps were uneven, some knee-high, and the Wall curved like a serpent over the ridges. Yet the fresh mountain air and the excitement pushed us onward. In 40 minutes, breathless but elated, we stood at the peak.

From there, the Wall stretched into the horizon. Sujan bhai and I exchanged a smile. We were standing where soldiers once kept watch, centuries ago, scanning these same ridges for approaching enemies. The thought sent shivers down my spine.

How had they built this, hundreds of years ago, without cranes or bulldozers? I imagined workers hauling stones weighing hundreds of kilogrammes up these slopes, using only their hands, wooden carts, and simple tools. In the Ming era, they even mixed lime with sticky rice to make mortar, an ingenious solution for its time.

I studied the watchtowers, perfectly aligned along the jagged mountain line. Without drones or the advanced equipment we have today, like lasers, their precision is uncanny. Every stone seemed to hold the memory of human sweat and skill.

From the peak, I started to notice the finer details: the rough texture of the stones, the small watchtowers along the ridges, and the way the Wall merged with the mountains as if it had grown from the earth itself.

The Great Wall is often mistaken for a single wall, but it is a series of walls and fortifications built and rebuilt over many centuries. Work began as early as the 7th century BC, but the section beneath my feet dated to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). At its height, the Wall stretched more than 21,000 kilometres, weaving natural barriers like mountains and rivers into its defences. It was built to repel nomadic invaders from the north, especially Mongols and other steppe tribes.

Pausing in a watchtower, I imagined the life of a soldier posted here: breathtaking but lonely views, freezing winters, and scarce food. Many never left, their lives and deaths becoming part of the Wall itself.

Tourists see postcard-perfect battlements and scenic landscapes. But the Wall is also a memorial to the human cost of empire-building. Thousands of workers and soldiers died in its construction and defence. That sacrifice lingers in its stones.

By midday, the quiet was gone. Footsteps echoed, cameras clicked, and voices in many languages filled the air. Yet, the Wall, which survived invaders, storms, and centuries of neglect, remained the main character.

China has preserved certain sections of the Wall, especially those near Beijing. I was struck by how it continues to be a symbol of China's national identity.

With the sun at its highest, we began our descent. Walking down was harder than climbing up — our legs trembled with every step. Still, the satisfaction was immense.

At the cable car station, I turned back for one last look. The Wall snaked into the distance, glowing under the afternoon light. It felt less like a monument and more like a living thing, breathing with the memory of those who built, defended, and now preserve it.

The Great Wall's claim as a wonder of the world is well earned. But what makes it truly remarkable is not its length or height — it's the way it invites reflection. Here, ambition meets endurance. Here, the past whispers to the present that greatness is built with both vision and sacrifice.

For me, it wasn't just a tourist stop. It was a reminder of what humans can accomplish with determination, and of the costs often hidden behind great achievements.

As our bus rolled back to Beijing, fatigue settled into my bones, but so did gratitude. This last-minute detour had become the highlight of my entire 11-day journey in China.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments