El Diego: The making of Maradona

A God, a cheat and everything in between -- Diego Armando Maradona was called it all.

He was a flawed rebel, who spoke as he wished, made mistakes, owned up to some, deflected most, took everything personally, and always carried his heart on his sleeve.

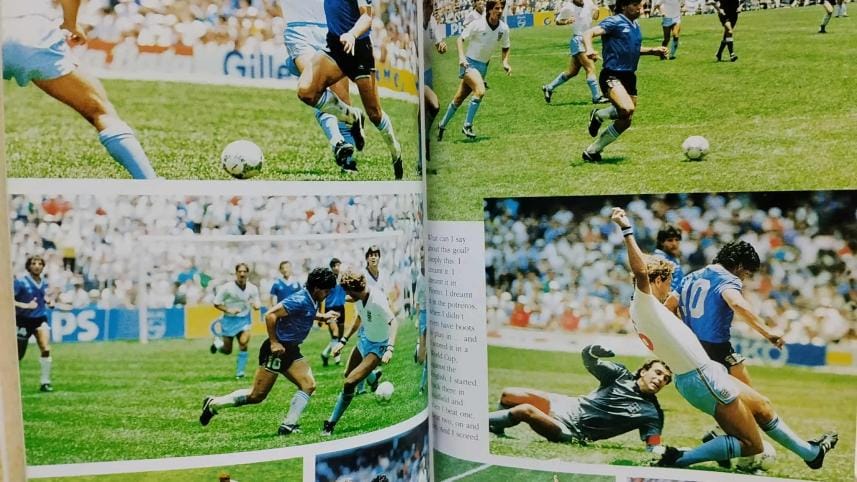

On the pitch, Maradona was the embodiment of football's poetry and chaos. His performances for Argentina in 1986 and for Napoli in the late eighties elevated him beyond greatness -- he became a symbol of resistance and beauty in equal measure.

Biographers from across the world, in numerous languages, have tried to capture his life on paper. Songs -- some flattering, others not as much – have been written about him; and he has been the subject of many academic research papers, leading to the creation of an academic sub-field called 'Maradonian Studies'.

So, if a person wants to dive into the world of Maradona, he or she has plenty of options to choose from.

But if one wants to truly understand Maradona, isn't it better to hear straight from the horse's mouth?

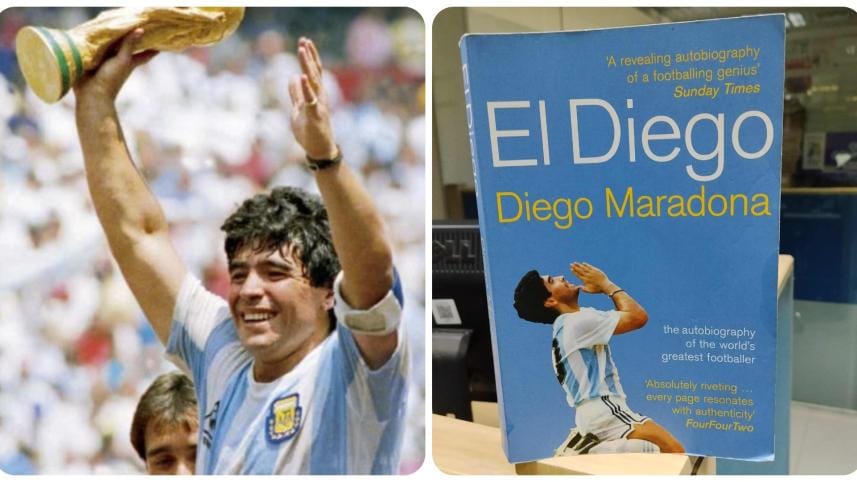

'El Diego' -- Maradona's only autobiography, where he spoke about his entire football career -- presents that opportunity.

'El Diego'

Originally published as 'Yo soy el Diego' in Spanish in October 2000, its English edition, translated by Marcelo Mora Y Araujo, was released in the UK in 2005.

The book is a detailed account of Maradona's football career told from his perspective.

The first thing that springs out of the book is its colourful language. Swear words are used freely, Argentinian sayings like 'take the cat's milk', 'give the dog its face back', are kept unchanged to convey the essence of how he spoke.

This decision from the translator added to the authenticity of the text, as rather than reading like a sanitised description of what had happened, it felt like Maradona was there in the room with the reader, with a lit Cuban cigar between his lips, regaling his life story.

His opening line explains the intentions behind writing this book: "Sometimes I think that my whole life is on film, that my whole life is in print. But it's not like that, it's not like that at all, there are things which are only in my heart -- that no one knows. At last I have decided to tell everything."

In the next 286 pages that followed, he detailed his meteoric rise in Argentine football, his complicated relationship with Argentinians, his struggles in Barcelona, the ecstasy and disappointments of his time in Napoli, and the triumph and heartbreak he experienced in World Cups.

He dove into uncomfortable territories of his life as well, like his well-known cocaine addiction, his torrid relationship with people in football administration, and the bans he suffered for substance abuse.

He shed light on what drove him as a player, how a young boy from the Ivory Coast, knowing his childhood name Pelusa, kept him from retiring from the game in 1981, and what led to him punching Carlos Bilardo, the man who coached him to the World Cup triumph.

After reading it from start to finish, some patterns emerge, which offer a better understanding of Maradona the footballer and the person, and how both intermingle to create the most beloved and controversial figure in the game.

Bronca: Maradona vs the world

"When I was left out of the final squad of 22 [for the 1978 FIFA World Cup], I realised that bronca, or anger, was a fuel for me. It really got me revved up. I played best when I was after revenge."

One does not come out of a working-class family in Fiorito to rule the football world without extra motivation. For Maradona, it was his thirst for revenge.

The triumph in the 1986 World Cup was fuelled by the conflicts he had with previous captain Daniel Passarella, the Argentinian media and fans who didn't believe in the team.

Winning the Scudetto for Napoli after 60 years was fuelled by the blatant racism Neapolitans faced from the rest of Italy, something that didn't sit right with him from the start.

In the 1990 World Cup, when Argentina lost to Cameroon 1-0 in the group stage in Milan, a match where the locals supported the African underdogs, Maradona famously quipped after the game, "The only pleasure I got this afternoon was to discover that thanks to me the people of Milan have stopped being racist. Today, for the first time, they supported the Africans."

From the looks of it, Maradona actively searched to make someone his enemy. It could be anyone -- an opponent player or coach, his teammate or coach, his club management, the media, the fans, even the president of FIFA -- he always felt he was being attacked and used this anger to push himself to achieve success.

When Diego let the tortoise get away

'Letting the tortoise get away' is one of the many Argentinian phrases Maradona used in the book, one that roughly translates to someone reacting slowly to a situation, not doing the right thing at the right time.

In Maradona's life, he has been guilty of it plenty of times.

Self-admittedly, he began taking cocaine in 1982 in Barcelona and even though he said, "Cocaine, instead of motivating you, discourages you, it dulls you… it's no use for football and it's no use, either -- I've only just learnt this -- for life," he was never able to fully implement it in his life.

When he was in Napoli, he knew Camorra -- the Neapolitan mafia -- was bad news but couldn't help but get fascinated by that "seductive world", and paid the price for it.

His long-time agent Guillermo Coppola was allegedly the one who supplied him drugs, but Maradona did not blame him one bit, saying, "Coppola could never have got me into drugs because when I started, in Barcelona, he wasn't even with me. Full stop."

Coppola was arrested in Argentina in 1996 on cocaine charges, but Maradona vouched for his friend's innocence even then, as he blamed Judge Hernan Bernasconi, who gave out the verdict instead, saying he was "responsible for depriving my friend Guillermo Coppola of his freedom."

The human side

The most telling aspect of the book was how Maradona laid bare his human side.

He spoke about how he felt he was a "prisoner of fame."

The pressure of always being the best player on the pitch took a toll on him as he pleaded, "Didn't Maradona have the right to be average, once in a while?"

He was also burdened by the responsibility of bringing joy to a country like Argentina that was going through economic and social turmoil.

"People have to understand that Maradona is not a happiness-making machine."

He was also overwhelmed by how people camped outside his home for days after he had won the World Cup, saying, "Nobody deserves this, not Maradona, not anybody… I felt it was too much… all I'd done was win a World Cup."

Separating Diego and Maradona

In the book, Maradona often referred to himself in the third person, as if he were talking about a separate entity. This tendency supports the theory of many Maradona researchers that Diego and Maradona are separate entities.

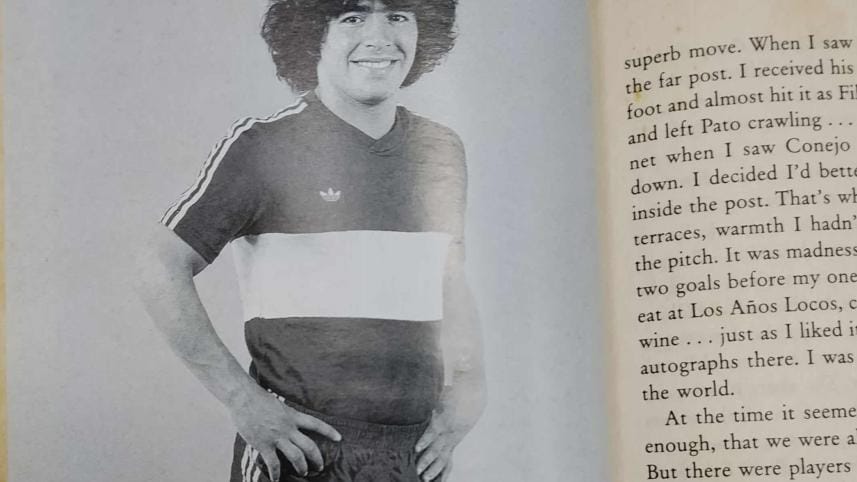

The theory is that Diego was the little boy from Fiorito, who played football from dawn to dusk, loved his family, and only wanted to play for Boca Juniors and the national side.

That kid was then thrust into the spotlight at a very young age, making his first-division debut at the age of 16 and national debut at 17.

In just three years, he had jumped from the ninth division of Argentine football to the national side, and to cope with the meteoric rise, the young Diego created the persona of Maradona -- the brash-talking, always confident, world-conquering footballer who didn't shy away on or off the field.

In the book, his dual personality is visible, making the reader feel compassion for Diego, who had to deal with the weight of being Maradona.

What's missing

Even while promoted as a tell-all book, and it did say plenty, there are many aspects of his life he either completely ignored or just gave a slight hint of.

For example, he spoke about going out at night without his wife but didn't outright talk about his extramarital affairs or about his illegitimate children.

He didn't say anything about his lengthy detoxing rituals to get ready for a match after a night of drug abuse or about the tax fraud case against Italy, for which he received posthumous clearance in January 2024.

Maradona was far from a perfect person, something he never claimed to be. And this very quality made him accessible to the masses, made the common man feel a connection with him, and consider him as one of their own.

The world lost Maradona in 2020 and is still feeling his absence. Love him or hate him, one cannot deny his status as the most beloved and colourful personality in football.

And after reading El Diego, one's love affair with Maradona can only increase.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments