A sneak peek into favela life

Rio de Janeiro has many faces. It is fraught with such extremes that it's quite hard to fathom the true nature of this beautiful city. Brazil's most cosmopolitan city, Rio enthralls its tourists with a number of iconic landmarks and natural beauty spots while at the same time throwing in some sad aspects of life.

As the Olympic Games neared its end and the number of daily events thinned out, we were left with time to take a look around the tourist attractions of Rio de Janeiro. A day and a half's excursion was enough to leave us with an eye-opening experience. Here is the first part of a two-part travelogue on that experience.

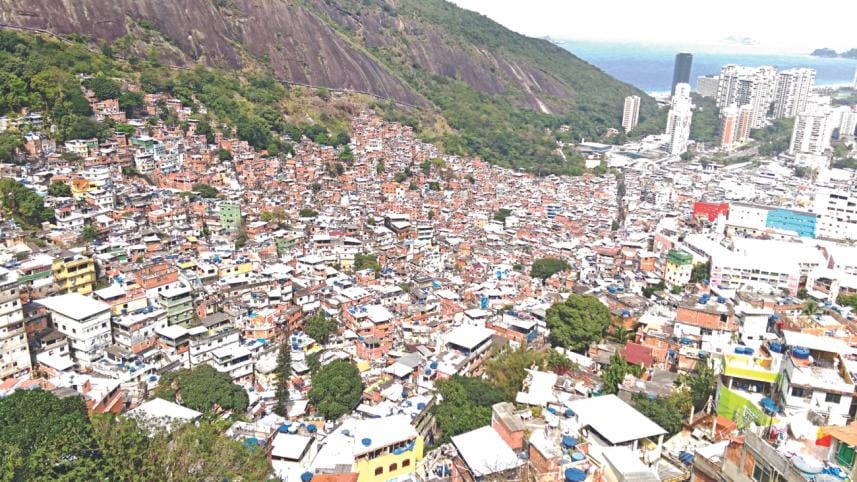

A fellow Bangladeshi sports journalist and I spent the first day of the excursion in a township named Rocinha, located towards the centre of the city. Favelas are notorious for their poverty and violence, and thanks to world media's attention turned on Brazil for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the Rio 2016 Olympics, these favelas have earned a lot of column inches in international media. With that knowledge, we cajoled our tour operator to arrange a tour to Rocinha, which is the largest favela in Brazil, sheltering close to 70,000 people over 355 acres of hilly land.

Our guide for the day, Monica, herself came from one of the 700 favelas of Rio de Janeiro and that helped us have a valuable and unbiased insight into what these favelas were all about. She guided us through the narrow allies of the township which slope down towards the plain. We were first taken to a souvenir shop at the top of the hill and the view from its balcony put some of the things we had read into context.

It was a view quite like one in Dhaka or Mumbai or any other megacities of the third world. From the top, Rocinha looked like a jumbled assortment of one-storied tin-shed houses, with tall skyscrapers bordering the slums. Most favelas of Rio, Monica says, are usually located within close reach of posh neighbourhoods.

Rocinha is sandwiched between Sao Conrado and Gavea -- two of the upscale areas of the city -- and despite the close proximity, Rocinha is kept by its wealthy neighbours at arm's length as its people remain poor and desperate. And that is what brings tourists to this place. It is not the chic architecture mansions and modern skyscrapers that attract tourists, rather it is the poverty of Rocinha that lures tourists from around the world.

Poverty, it seems, is an exhibit and the exhibit is selling big here.

A walk down the steps of the narrow alleys makes things more vivid. The steps which lead to a slightly broader alley are marked by graffitis on the walls of the houses, each one telling a unique story of hunger and angst.

The elderly sit by the small windows of their houses or at the doorsteps as we pass by while Monica explains the history of the favelas. "The desperately poor people of the north come to Rocinha with a dream of making a life in the big city, but eventually the dream never realises," Monica says. "And the fact that the government provides most utilities for free encourages these people to not leave these favelas. Things too are very cheap here."

Things are indeed cheap in the favelas. A shoe of moderate quality, which sells for around 300-500 real in the city markets, can be found at a third of that price at the shops of Rocinha.

The low cost of living and free utilities is one reason, apart from poverty and lack of education, which drives the young men and women of these favelas into violence, drug peddling and other crimes. Monica says things have, however, improved a lot since police forces trained by US SWAT teams were deployed inside each of the favelas some eight years ago to contain the violence ahead of the two major sporting events.

Statistics say the rate of crime has come down drastically, and from our time spent in Rocinha, we did not notice any drug peddlers or vagabonds loitering around the streets. The people we saw on the streets were mostly busy workmen, minding their jobs, however pitiful that job might seem to the eyes of the rich.

As we made our way towards the end of the favela, walking through the zigzag alleys, we stumbled upon a unique cultural exhibition. It was a combination of dance and martial arts, named Capoeira, imported from Angola and Congo along with the slaves. The Africans held on to the tradition and spread it around the locals as well. There were young boys and girls taking part in this exotic art form, and we were asked to join them in their rituals. The end of the tour finished in a cheerful mood, much to our surprise.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments