Indigenous Lives on Screen

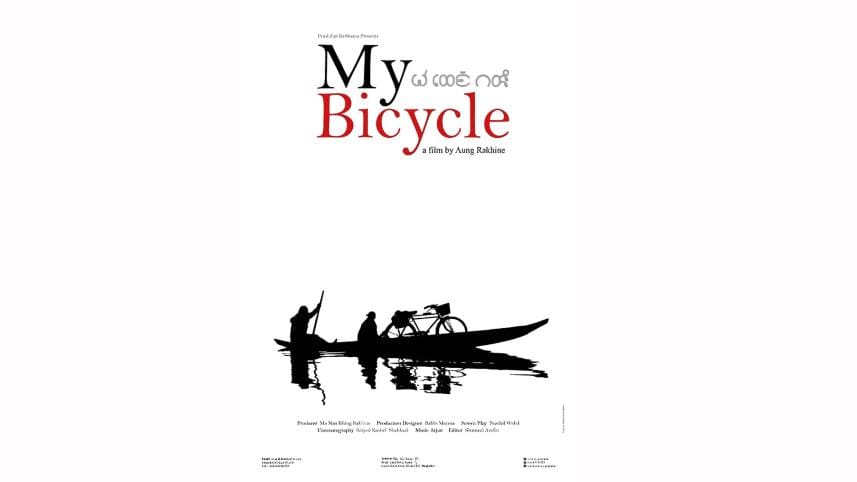

Aung Rakhine, director of Mor Thengari (My Bicycle, 2015)—the first Chakma-language feature—shares his vision for portraying Bangladesh's indigenous lives, as he prepares his next film, Mro, on the stories and beliefs of the Mro community.

The Daily Star (TDS): As a Rakhine filmmaker, what drew you to make a film in the Chakma language?

Aung Rakhine (AR): I studied in Rangamati during class nine and ten, which brought me both geographically and socially closer to these communities. I witnessed their political and cultural realities firsthand, and from that experience came the inspiration to make this film. Behind it lies a political dimension as well, since the Chakma community is one of the most significant among Bangladesh's indigenous minorities—not only in terms of numbers but also in their movements for rights. Their struggle for survival is perhaps the most visible compared to other minority groups. That is why I often say: if the Chakma people can survive in Bangladesh, then other ethnic groups will also endure. This cinema, therefore, is also a way of acknowledging and appreciating all these communities.

The Chakma people, despite often lacking even proper roofs over their heads, place a remarkable emphasis on education. Almost every household has someone pursuing studies, and their presence is notable not only nationally but also internationally. Naturally, opportunities are opening up for them, and as a community they have always contributed to the nation in many ways.

For me, making the first feature in the Chakma language was an act of appreciation—rooted in a practical understanding of their lives and struggles. I should also note that several films had been made in Chakma before, but My Bicycle was the first to gain international recognition, both within the industry and in terms of its broader journey.

I haven't been able to show it widely yet, but there have been some personal screenings—I mean, in universities, groups, and clubs. During the July movement, quite a few open shows were held here and there in a scattered way. But officially, I couldn't released it in Bangladesh.

The story is basically about a man—a middle-aged man—who, unable to survive in the city, returns to his village on a bicycle. But the "village" here is set in the hills, where life itself is a constant struggle because the hills have been diminished so much. The film portrays that struggle for survival. Then, after going back with his bicycle, he starts a small business. So, the whole thing is the story of that man's struggle—with elements of love and romance woven into it as well.

TDS: Could you tell us about your upcoming projects, particularly Mro?

AR: Actually, no two works are ever the same. My first film, My Bicycle, was a full-length feature, while my second, the Bangla short film Post Master, was completely different in style and approach. Now, I am planning a new film, Mro—which is neither like My Bicycle nor like Post Master. The Mro are an indigenous people living in Thanchi, Bandarban. This project takes an anthropological perspective, exploring many stories behind their lives. One particularly intriguing aspect is that it deals with the world's newest religion, established in 1985. So, while it is fundamentally a story, it is approached through a rich anthropological lens.

We have been researching this film since 2019. At present, however, we are facing a funding crisis. I do not have a producer yet, so whether we can start shooting this year or next depends entirely on financial support. My first film was funded through family support and crowdfunding—my wife even sold her jewellery to help cover costs. That project was essentially a no-budget film.

This new film, however, is on a much larger scale, with a budget of around one and a half crore taka, and we hope it will be completed by 2028. Beyond that, I have plans for 2032 or 2033 to create a film about my own ethnic community, the Rakhine people—a community that has never been represented in cinema before.

TDS: As an independent filmmaker in Bangladesh, how do you see your place in the industry, and what keeps you motivated despite the challenges?

AR: All over the world, whether they are called filmmakers or artists, they more or less share the same identity. But in Bangladesh, independent filmmakers like us are still not fully recognised—neither by audiences nor by business circles. The mindset of promoting art or supporting it has not yet taken root here, and I do not know when a sustainable cinema market will truly emerge in this country.

However, the global market is now opening up in promising ways, and I am working with that in mind. There is no reason to be frustrated. For me, making films is not just about ambition—it is about responsibility and commitment. It is a professional duty to my community and to Bangladeshi cinema as a whole.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments