How many more workers have to die before impunity ends?

"Unknown 14, Unknown 15, Unknown 12"—such numbers were marked on the white plastic body bags holding the charred remains of seven or eight garment workers inside the morgue. The rest of the bodies were kept in another morgue's freezer. According to available information, the death toll stood at sixteen—nine men and seven women. Amidst the burnt remains, one of the bodies still had its eyes open.

From one of the body bags, the raised hand of "Unknown 14" was sticking out—perhaps a final desperate attempt to survive. The air felt suffocating, heavy, and unbearable. I hurriedly stepped outside. In front of the emergency morgue, a few relatives of the victims were still waiting—hoping to identify their loved ones. The official in charge opened the door again. I wondered—how will these families find their people? How will they accept what they see? How will they carry such a horrific memory for the rest of their lives?

Overwhelmed by these thoughts, I left for the burn unit to meet the injured—Shukuruzzaman, Sohel, and Mamun. I could meet only two of them; Sohel was not in a condition to talk. From the others, I learned fragments of what had happened. I felt it would be cruel to ask too many questions. Their bodies and minds still bore the wounds of that terrible night.

It was Tuesday, 14 October 2025. Mirpur's Shialbari neighbourhood—around nine kilometres from Dhaka's bustling Farmgate—was just beginning to stir. As on any other morning, the rhythmic sound of workers' footsteps filled the narrow lanes. Among them were fourteen-year-old Mahira Akter, a newly married couple of seven days, and others—Tofail Ahmed (21), Nargis Akter (18), Nure Alam (23), Sanowar Hossain (22), Abdullah Al-Mamun (39), Rabiul Islam Robin (19), Nazrul Islam (40), and Muna—unaware that this ordinary morning would be their last.

For more than fifteen years, workers in Bangladesh have suffered the same recurring tragedies, born of a culture of impunity. Time after time, factory owners have evaded accountability through political connections and influence. In the post-uprising period, can we afford to allow this pattern to persist?

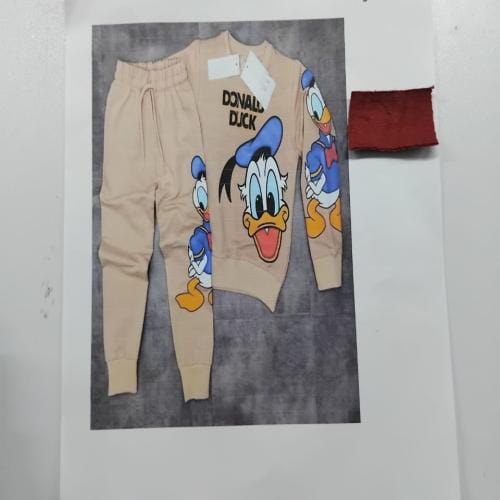

Arian Fashion (some called it Anwar Fashion), a small garment factory employing 35 to 40 workers, stood opposite Alam Traders, an unauthorised chemical warehouse. The workers produced hoodies and sweaters—sold in local markets and exported to Saudi Arabia under the brand Texora Global Ltd. Around 11 a.m., a deafening explosion erupted, and flames and smoke engulfed the building. The roof door was locked, and the narrow staircase below offered no escape. Even children aged between fourteen and fifteen were trapped inside, unable to make it out alive.

When we visited the site the following day, locals, workers, and relatives stood in stunned silence. The fire had been so fierce that rescuers could not enter the warehouse.

For more than fifteen years, workers in Bangladesh have suffered the same recurring tragedies, born of a culture of impunity. Time after time, factory owners have evaded accountability through political connections and influence. In the post-uprising period, can we afford to allow this pattern to persist?

We have long demanded reforms to the Labour Commission and amendments to labour laws to ensure workers' rights and dignity. The interim government's priority list, we were told, placed the labour sector at the top—to bring it up to international standards. We trusted those promises. Yet the Mirpur tragedy has again stirred our doubts, fears, and anger. The cries of these sixteen workers seem to echo through history—reminding us of Tazreen, Hashem Foods, Chawkbazar, Tikatuli, and Rana Plaza.

History sometimes teaches us lessons—but often, we fail to learn from our own mistakes. Let us hope that this time, the interim government will draw strength from history and set an example by ensuring justice for the victims of Mirpur. Alongside labour law reform, the government must also establish accountability for such structural killings. It must explain how unapproved chemical warehouses and hazardous establishments are allowed to operate in residential areas—and take immediate action to end this negligence.

We must remain vigilant before the coming election. The new social contract of the new Bangladesh cannot exclude the workers. The dying cries of those sixteen workers still echo around us—we want justice, we want dignity as human beings, we want the guarantee of a natural death.

The number of those burnt to death—sixteen—may yet rise, as more cries of anguish join their ranks. The voices demanding justice for those lost at Rana Plaza, Tazreen, Hashem Foods, and countless other tragedies return to haunt us once more. None of us can claim innocence.

We can only hope that the cries of the dead reach the ears of the government. They must not forget—those "unknown" workers who died nameless were the very ones who gave their lives in the people's uprising, alongside students and ordinary citizens.

The progress of Bangladesh's labour sector and the dignity of workers' lives are inseparably linked. If we are to achieve democratic transformation, we cannot separate workers' rights, safe working conditions, and human dignity from national economic development. The new Bangladesh cannot bear another death born of negligence, nor another dream crushed by indifference. It must be built on unity and justice.

We must remain vigilant before the coming election. The new social contract of the new Bangladesh cannot exclude the workers. The dying cries of those sixteen workers still echo around us—we want justice, we want dignity as human beings, we want the guarantee of a natural death.

To prevent another tragedy like Mirpur, justice must be ensured. The culprits must be punished, and warehouses must be removed from residential areas. Equally necessary is a new social order—one that belongs to the workers. We need a new image of the labour movement, and a new class of entrepreneurs who will see workers not merely as tools for profit but as partners in progress.

Taslima Akhter is the President of Bangladesh Garment Sramik Samhati (BGWS) and the Bangladesh Trade Union Federation. She is also a Member of the Labour Reform Commission (2024), a Recipient of the Rokeya Padak (2024), and a Member of the National Tripartite Consultative Council (NTCC).

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.