Why Zahir Raihan matters more than ever after the August uprising

When a colonised people rises to claim sovereignty, culture is never a bystander. The fight for independence and the flowering of culture are not two separate processes. They work hand in hand, complementing one another, sharpening each other into tools of resistance. This idea was articulated clearly by Frantz Fanon in 1959. He argued that the struggle for liberation gives birth to cultural identity in its fullest form, and that literature, art, and folklore become weapons in the larger war against oppression.

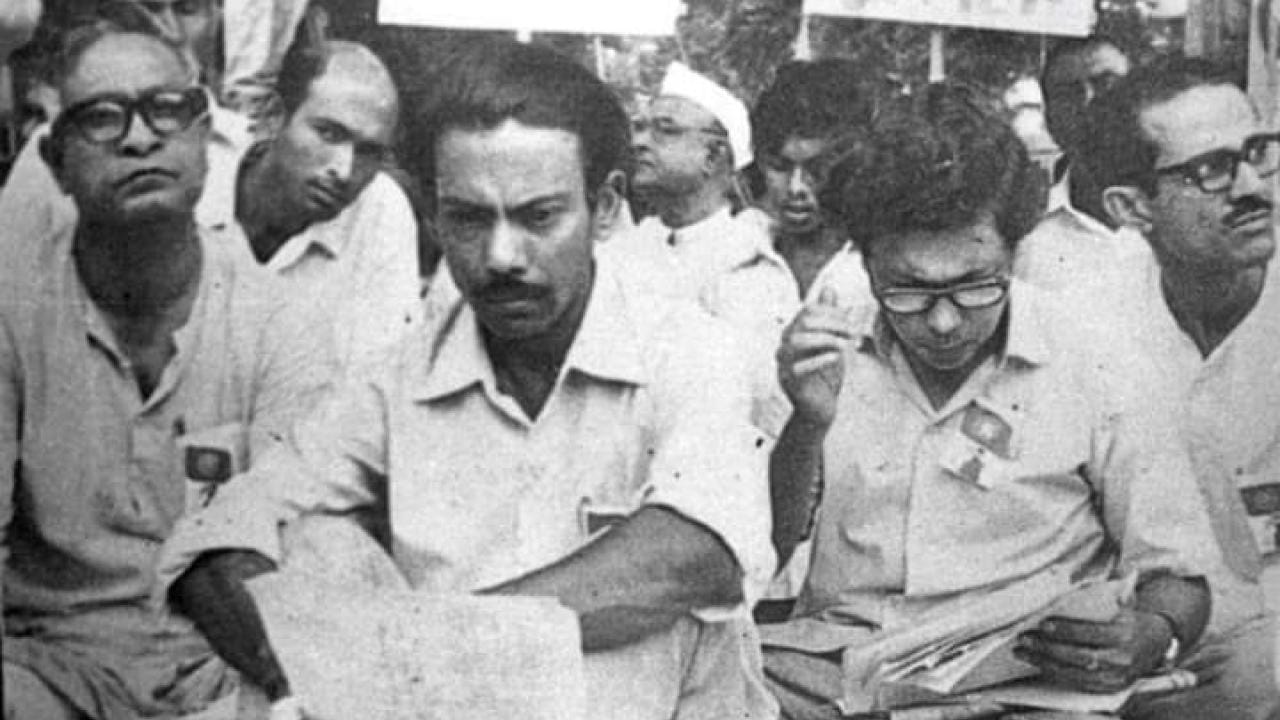

Zahir Raihan stands as one of the most striking examples of this truth in Bangladesh's history. His life and works show how art and struggle could merge into one.

In 1971, when Pakistan launched its brutal crackdown on East Pakistan, many intellectuals either went into hiding or slipped across the border into India, choosing to remain passive. Raihan refused such a path. Instead, he crossed into Kolkata, raised funds for the war effort, and then went a step further—he entered battle zones with guerrilla fighters to document the war on film.

This was not simply an act of recording events. It was an act of defiance, a way of building an archive of truth that could never be erased by official denial. Raihan directed Stop Genocide and A State Is Born, and arranged for Alamgir Kabir and Babul Chowdhury to make Liberation Fighters and Innocent Millions.

These films stand today not just as documentaries, but as urgent calls to the world, insisting that the suffering and resistance of Bengalis be recognised.

Raihan's cultural battle did not begin in 1971. Long before the Liberation War, East Pakistan's writers, artists, and intellectuals had already begun resisting Pakistani colonialism through cultural means. As early as 1952, during the Language Movement, the spread of Bengali literature and Rabindra Sangeet, along with the revival of folklore in cinema, became acts of defiance.

Raihan was a leading figure in this wave. In 1966, his film Behula was released. On the surface, it was a retelling of a popular folk tale, the story of Chand Sadagar and the goddess Manasa. But beneath the myth lay sharp political undertones.

Speaking to Kolkata journalist Partha Chatterjee, Raihan explained: "This is the story of Chand Sadagar, a folk tale of Bengal. It has a universal human appeal. But the censors and religious hardliners were furious. I must be a kafir—why else would I make a film on Hindu mythology? Yet Behula carried a modern message. At its core, it was about the struggle of man against the gods."

The film was temporarily banned. After much delay it was released, but with new, sweeping restrictions: no films in Pakistan could portray Hindu deities, no female characters could wear sindoor, and no woman could be addressed with the prefix "Shrimati." For Raihan, this was proof that the authorities feared any cultural expression that might nourish Bengali identity.

Fanon had argued that folklore, once dismissed as old and irrelevant, could be revived during liberation struggles. Storytellers take ancient tales and retell them in ways that feel immediate, even urgent. Instead of beginning with "a long, long time ago," the tale is told as if it could happen today or tomorrow. The eternal conflict between good and evil becomes an allegory for the struggle against colonial power.

Raihan did exactly this with Behula. The story of Chand Sadagar's defiance and Behula's courage became metaphors for East Bengal's own resistance against oppression. In the myth, Behula risks everything to confront unjust divine curses and to reclaim her husband's life. To Raihan, this was not just myth; it was poetry of the people, where humans rebelled against imposed authority.

This narrative could be read in feminist terms, highlighting Behula's agency, but Raihan's own approach was closer to a Marxist reading: the story as an allegory of class struggle, where the oppressed rise against their masters.

The timing of Behula's release—October 28, 1966—was crucial. The India-Pakistan conflict was at its height. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had announced the Six-Point Programme demanding autonomy for East Pakistan. Demonstrations in support of Six Points were being met with gunfire. Newspapers such as Ittefaq were banned. The dream of national liberation was becoming increasingly visible.

Against this backdrop, Raihan's choice to turn to folklore was not accidental. In Behula, the rebellion of the oppressed against the master became a symbolic narrative for East Bengal's own political struggle. The West Pakistani rulers recognised the danger in this and sought to smother the film by branding it "communal." This was part of a larger pattern. Later, they would label the Liberation War itself as "anti-Islamic." By mixing religion with nationalism, they attempted to create a hybrid identity that blurred the demand for true freedom.

The suppression of cultural symbols by the Pakistani authorities extended into Raihan's later films. His 1969 masterpiece Jibon Theke Neya also became a target. Raihan recalled how the censors objected to characters eating rice from bronze plates, claiming that bronze was a marker of "Hindu culture." The pettiness revealed the depth of fear the authorities had of cultural independence.

For Raihan, this was not just a bureaucratic nuisance; it was a deadly threat. He believed communalism was the greatest enemy of the nation. After independence, he lamented to Partha Chatterjee:

"Our biggest enemy is communalism. I fear that we might once again fall into its trap. Religion must be removed entirely from state affairs. Religion is a matter of the heart."

The essence of the Liberation War had been just that: a secular and democratic state, free of religious privilege, where everyone would be equal in the eyes of the law. But the reality of post-war Bangladesh diverged from that ideal. The state clung even more tightly to religion, poverty increased, and injustice became routine.

Raihan's death came swiftly, brutally, and symbolically. On January 30, 1972, just weeks after independence, he was lured from his home and killed. His killers were linked to the forces behind the murder of intellectuals, including his elder brother Shahidullah Kaiser. Raihan had been gathering evidence and had even promised to release a white paper. That made him a threat. Eliminating him was not only the silencing of a man but the extinguishing of a future where Bangladeshi cinema and literature might have flourished with even greater brilliance.

Zahir Raihan was more than a filmmaker. He was also a novelist and short story writer, a thinker who embodied the fusion of culture and politics. His works carried the spark of national consciousness, and had he lived, Bangladesh would likely have gained far more international stature through his art.

Fanon had insisted that national consciousness, born out of struggle, can open doors to international recognition. But he also warned that national consciousness is not the same as nationalism. It is more fragile, more complex, and full of contradictions. Raihan understood this complexity. He was an artist shaped by struggle, someone who held the weight of national consciousness within his work.

His murder, like that of so many of our finest sons, was a wound inflicted by our own hands. With him, we lost not only a visionary filmmaker but also a future where culture and politics might have remained bound together in the spirit of liberation.

Bidhan Rebeiro is a writer, editor and film critic.

References

Partha Chatterjee, Jahir Raihan ke Chintam, Prasad: Bangladesh Issue (Bangladesh Liberation War in West Bengal's Film Journals), (Dhaka: BPL), 2015

Anupam Hayat, Zahir Raihaner Chalachitra: Potobhumi, Bishoy O Boishishto, (Dhaka: Dibya Prokash), 2007

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, (London: Penguin), 2001

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments