Why was Sher-e-Bangla so popular?

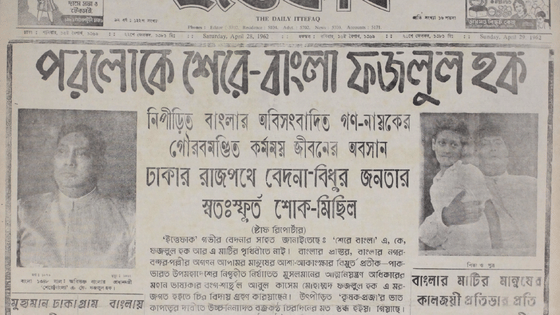

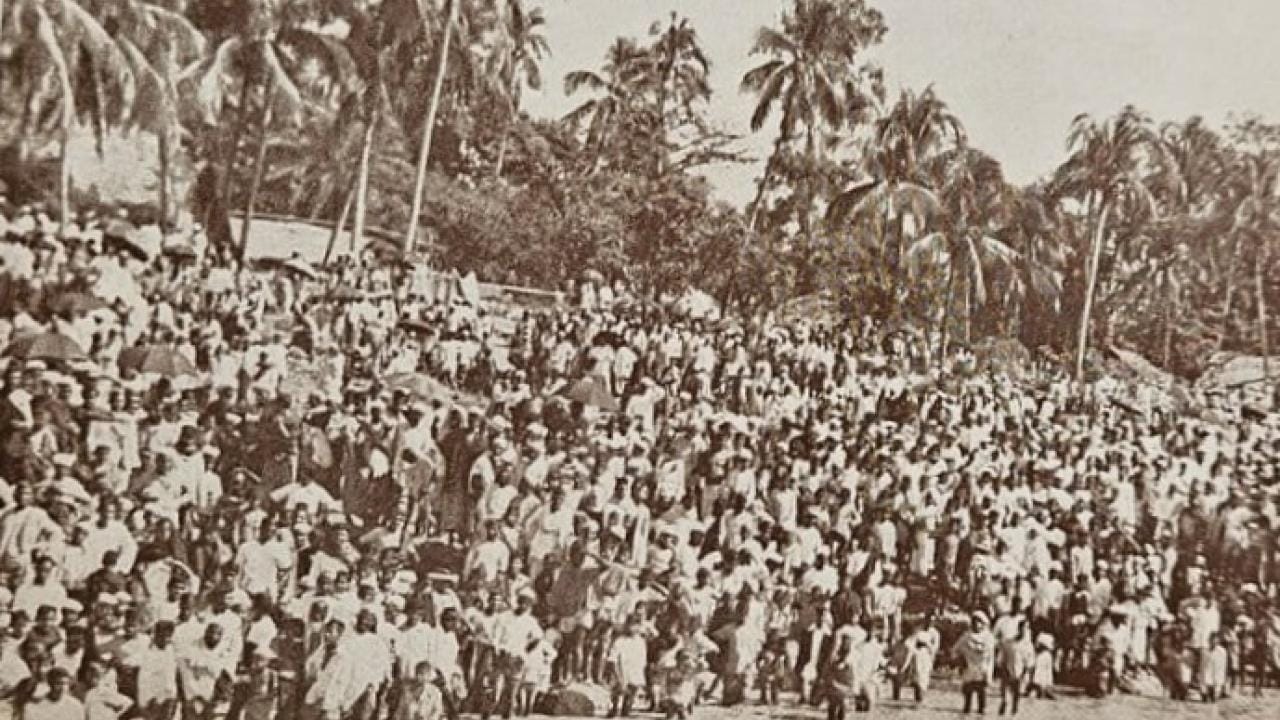

Abul Kasem Fazlul Huq, popularly known as Sher-e-Bangla, passed away on April 27, 1962 at the age of 89, after spending nearly a month on the sickbed of Dhaka Medical College, bringing to a close a political career that spanned over half a century. Though he had led a largely secluded life in the last two to three years before his death, his passing rekindled the deep affection and admiration the masses held for him. The entire country came to a standstill: Radio Pakistan suspended its regular programming to broadcast only Quranic recitations, flags flew at half-mast nationwide, and schools were closed in his honour.

The Pakistan Observer of 28 April 1962 reported:

'As the news of the death spread in the city and suburbs like wildfire, thousands thronged the Medical Compound and within a few minutes the hospital area turned into a veritable sea of human heads. The stony silence of the hospital compound was being broken only by the sobs of thousands, and there, lying on a bier, was the mortal body of the great leader wrapped in immaculate white. The lips that had once swayed the minds of millions with their slightest movements were numb. The eyes that had swelled with tears at hearing the woes of anyone were closed forever.'

We heard of Hatem Tai,

the generous King of Yemen.

But we have seen with our own eyes

the Hatem Tai of Bangla Desh.

— Begum Sufia Kamal (1911–1999)

What differences did Sher-e-Bangla make as a political leader of his time that set him apart from others? What made him so popular among the masses of Bengal? Why did a large number of people 'burst into tears on streets, in offices, and in houses when they heard the news of his death'? Why did his death become a 'personal tragedy' for them?

Many of the writings after his death tried to decode the mystery of his popularity and charisma. The Pakistan Observer in 1966 described Huq's bond with the masses in near-mystical terms: 'he belonged to the people and the people belonged to him… Fazlul Huq was Bengal and Bengal was Fazlul Huq.' He was lauded as 'Sher-e-Bangla of the common man, for the common man and by the common man,' someone who 'lived like a common man in the midst of the common man.' A commemorative article published by The Dawn, written by Dilawar in the same year, echoed the same sentiment: 'Fazlul Huq was popular not because he was a great political leader. He was popular because he never considered himself above the ordinary man. He was one of them.'

The more significant aspect of Fazlul Huq, which was overlooked by most writers, was his role in shifting the ontological status of Bengali Muslim peasants, which was aptly identified by Abul Mansur Ahmed. In a memorial piece in 1968, he wrote, 'Many a politician of the country has performed or tried to perform political feats more spectacular in magnitude and graver in consequence than Fazlul Huq. But none could so occupy a permanent seat of worship in the heart of the masses as Fazlul Huq. Why? Because to Fazlul Huq the "masses" was not a vague and indefinite term like the public to be used to suit the convenience of the politician. To Fazlul Huq, the masses were a concrete, definite and identifiable, and overwhelmingly larger section of the populace, viz. the peasantry.'

The question is: was it possible for Sher-e-Bangla to speak for the community that Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak termed the 'subaltern'? One major concern of Spivak is that often the most oppressed (the 'subaltern', such as colonised women or the rural poor) remain voiceless in the public sphere because the 'terms of discourse' are set by the elite. According to her: 'Epistemic violence is visited on the subaltern… When they speak in their own name, they are not heard; …when they speak, [if] they speak not in their own name [but] in the name of the hegemonic discourse.'

Throughout his life, we can see a clear attempt to minimise the difference between his own social position—an upper-middle-class one—and the 'other' for whom he was speaking. He tried his best to support their process of self-recreation and to assert their subjectivity and agency. Yes, there must have been loopholes, there must have been gaps; perhaps it was not possible for him to make the unheard heard. But the attempts he made were crucial at that time and were indeed recognised by the very people for whom he made them.

2

Another feature, which in the Weberian sense was one of the major traits of charismatic leaders, was his understanding of the real needs of the people, which actually helped him emerge 'from within' the people's struggle.

In the 1930s, the Bengali Muslim peasantry was in desperation to come out of the existing system: to gain relief from feudal landlords (zamindars) and moneylenders. The impoverished people were struggling to manage their bread and butter. And Sher-e-Bangla took this as the main agenda of his politics. The signature slogan of his political party, the Krishak Praja Party (KPP), became 'Shobar Jonno Dal-Bhat' (rice and lentils for all), a simple promise of basic sustenance that felt almost miraculous to destitute farmers. For the first time, a major politician centred his agenda on the 'bread-and-butter' needs of Bengal's rural poor.

We find the same reflection in Abul Mansur Ahmed's writing: 'Indeed Sher-e-Bangla was the first statesman and politician to see that the politics of Bengal was in reality the economics of Bengal. By the same standard, to Fazlul Huq, the people of Bengal were in reality the peasants of Bengal. It was this political insight through which Fazlul Huq so deeply penetrated into the heart of the masses as no other leader could.'

3

Apart from holding high offices such as Mayor of Calcutta, Premier of undivided Bengal, and Chief Minister of East Pakistan, Sher-e-Bangla's life itself offers a rich study in charismatic authority. His legacy lives through countless stories that have inspired generations. I can recall at least three such stories from my late father, Sultan Ahammed, which I heard in my early childhood. The stories were of his generosity, bravery, and brilliance. These anecdotes played a significant role in shaping Sher-e-Bangla's legendary stature.

In a commemorative piece published in Azad on 27 April 1968, Principal Ibrahim Khan recounted some of these stories. One was about Sher-e-Bangla's contribution to the 'Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti' in Mirzapur, Kolkata. At a time when the Samiti was facing a financial crisis, Abul Mansur Ahmed and others approached Sher-e-Bangla for help. His initial reply was both witty and memorable: "My pocket is empty today, like the belly of a winter snake. Please come tomorrow at 5 p.m., let me see if I can collect something from the Kachari."

The next day, when Abul Mansur Ahmed and his companions returned, they saw two Kabuli moneylenders waiting at his door. Assuming the funds would go to them, they were surprised to see Sher-e-Bangla ignore the Kabulis and hand over all the money to the literary association. The Kabulis, enraged, said, "Didn't you feel ashamed borrowing money you cannot repay?" Sher-e-Bangla paid no attention to their remarks and walked away.

Another story from Principal Ibrahim is equally endearing. One morning, Israil Khan — a young lawyer from Tangail and a disciple of Sher-e-Bangla — received an urgent call to meet him at the Dakbangla. Without delay, he rushed there. Upon arrival, Sher-e-Bangla asked him to pluck kalojam (black plums) from a tree. Israil Khan obliged and gathered two and a half kilograms of fruit. Sher-e-Bangla immediately ate one and a half kilograms in one sitting and then confided that he hadn't eaten the night before due to lack of money. The jam, he said, helped 'quench the fire in his belly.' He then asked Israil to buy him a second-class train ticket to Kolkata.

4

The problem with charismatic authority is that it can be a double-edged sword. There is continuous pressure on the leader to meet the expectations of his followers. Once he fails to satisfy these expectations, the whole charismatic authority fades and the passionate loyalty of followers turns into sheer disappointment. Max Weber wrote, 'If proof and success elude the leader for long … it is likely that his charismatic authority will disappear.'

In the case of Sher-e-Bangla, the political affairs of the 1940s are the prime example of this. His departure from the Muslim League and alliance with the Hindu Mahasabha and a certain part of the Congress (known as the Shyama-Huq Coalition) to form the coalition government in 1941 took an unfavourable turn for him. Though, on paper, it was regarded as an attempt to unite Hindus and Muslims under a shared identity, in practice, it became a weapon for his opponents.

The Muslim League launched a fierce propaganda campaign portraying Huq as a traitor to the Muslim cause for 'closing ranks' with Hindus. And it worked accordingly. Many Muslim voters who had adored Huq for championing them now felt betrayed or confused by his partnership with the Mahasabha (a group some saw as hostile to Muslim interests).

The famine of 1943, which killed millions of people, added to this and intensified the anger. Although the famine was largely the result of wartime colonial policies and beyond any one leader's control, the Muslim League used this catastrophe to discredit Fazlul Huq and to undermine his acceptance among the people. Ironically, they appropriated much of his peasant rhetoric. Then came the idea of Pakistan, portrayed as a 'peasant utopia' where there would be no landlords and no poverty. Everything they did was very much aligned with the rhetoric of Sher-e-Bangla.

The Muslim League achieved two things successfully: the character assassination of Sher-e-Bangla and the appropriation of his political rhetoric. And this double bind worked with remarkable success. The evidence of this success lies in the result of the 1946 election: the League won a thumping victory, sweeping 87% of the rural Muslim vote in Bengal. The charisma had shifted — the followers who once saw Huq as their saviour had transferred their hopes to Jinnah's camp, believing Pakistan would deliver what Fazlul Huq ultimately could not within the colonial setup.

5

History always has a surprise in store. Though, with this landslide defeat, it was assumed that he was lost and his political career doomed, we can see him re-emerge in the politics of Pakistan after 1947. This part of his politics is a different story and requires a different evaluation. But what we can see is that the same people who rejected him in 1946 reappeared as his followers. His political career came to an end in 1958 when General Ayub Khan seized power through a military coup.

In the last four years of his life, he was in complete absentia. Upon his death in 1962, the outpouring of grief across East Bengal (and beyond) proved that the charismatic bond between Sher-e-Bangla and his people had not been severed at all – it had only gone dormant.

Abul Mansur Ahmed, in his article 'Sher-e-Bangla in Search of National Soul', identified two aspects of his life as the key to the secret chamber: 'One, his confident and unfaltering insistence that in all his quarrels it was his opponents who were mistaken and not he; two, his candid confession that he never tried to be the master of his fate but allowed chance to play her part in his life. This is very significant. Indeed, in my view, these two traits taken together are the key to the secret chamber of Fazlul Huq's life.'

We may find resemblances or differences between him and other great leaders of our history. But interaction with them in some way is more than necessary for us.

Mehedi Hasan is a writer and researcher. He can be contacted at mehedi7119@gmail.com.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments