The Pain of Water

"নদীর একটা দার্শনিক রূপ আছে"

"The river has a philosophical form"

—Adwaita Mallabarman

I.

"Titash was my dream," pledged Ritwik Ghatak. His words were read out at the premiere of his film in the Modhumita Cinema in Dhaka, while he remained hospitalised in Kolkata. He had not seen the final cut. The film was left in the hands of his Bangladeshi film crew, who assembled it through both received instruction and aesthetic judgement. In India, his film was tepidly received, poorly distributed, and until recently, largely ignored. Yet, it was the film that Ghatak staked his well-being and life to make; one that moved him across the anguished boundaries of nation and memory.

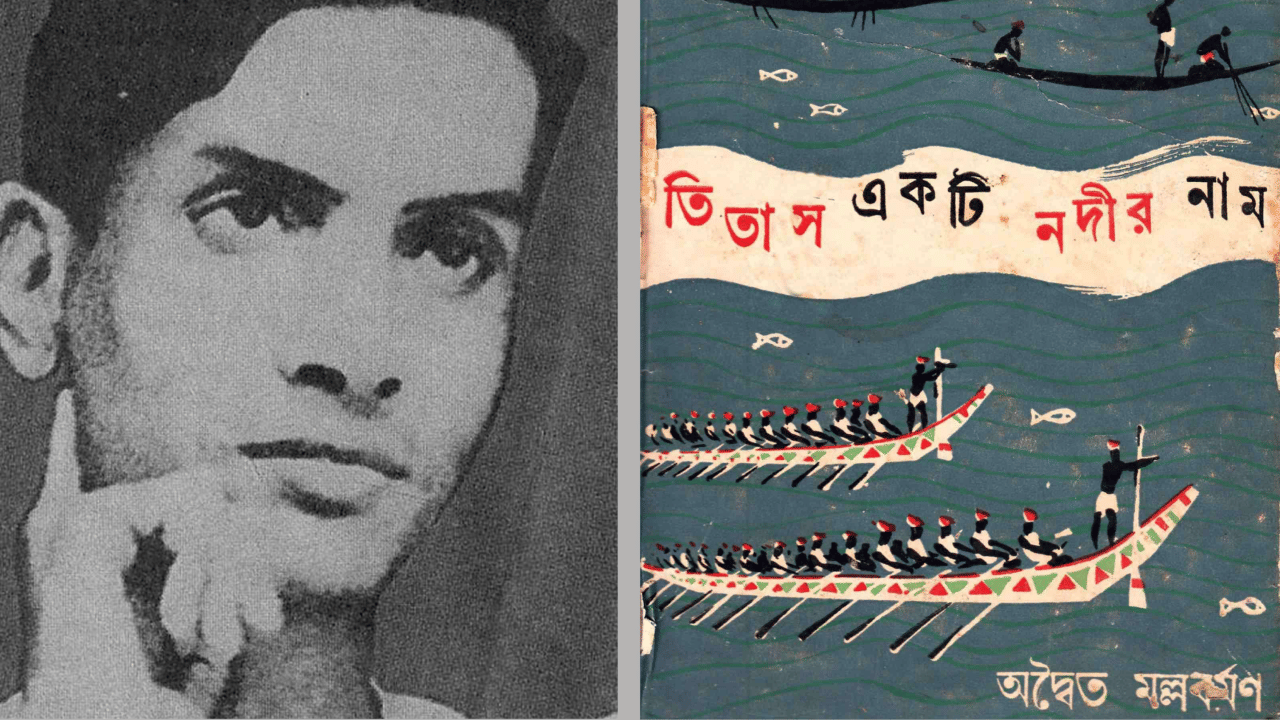

Through this film, he sought to retrace his childhood in East Bengal. Ghatak's guide and source material in this quest was Adwaita Mallabarman's Titash Ekti Nodir Naam ('A River Named Titas'). Published posthumously in 1956, the novel also memorialised a home left behind. Mallabarman depicted the river and Malo fishing community of his youth, and the erasure of both as the waters receded. As a narrative of ecological dispossession, his novel foreshadowed an uprooting of society not unlike what was to happen again to the Malo fisherfolk during Partition.

The river has long been a metaphor for time. For Heraclitus, the river figured a cosmic "ontology of momentary things," a restlessness of form. The Heraclitean dictum of panta rhei ('everything flows') echoes throughout these works. Historical time in Titash is fluxive. The river is not only a place but a motion. Friedrich Engels described this flux as the world's primitive but "intrinsically correct" conception: all things "constantly coming into being and passing away." But, whereas modernity believes in progress, the river believes in recurrence.

In Bengal, flux is not an abstraction. It is also a lived grammar, a deltaic temporality: an experience of cyclical creation and dissolution inscribed in riverine life. Mallabarman and Ghatak, moreover, experienced the flux of history through political displacements, through the liquid foundations of a region that underwent drastic reterritorialisations of its physical, environmental, and human geographies. Flux is not only the name of a philosophical musing, it also serves as a plausible analytic and aesthetic category for twentieth-century Bengali history. Gaston Bachelard wrote that "a being dedicated to water is a being in flux," dying every minute, endlessly renewed—thus, "the pain of water is infinite."

II.

"Titash is just an ordinary river," begins the novel. To place its origins in deep time would digress from the novelist's enframing point about the prosaic rhythms and relations between riverine and human time. Mallabarman was interested in the history of the non-monumental, the unrecorded instances that underlie most of recorded time: "No one will find [Titas'] name in history books, in any of the chronicles of national upheavals. Its waters were never tainted with the lifeblood of people from two groups locked in battle." But, "does that mean it is really without history?" Does it suffice if its banks are "imprinted with stories of a mother's affection, a brother's love, the caring of a wife, a sister, a daughter."

Mallabarman was born in 1914 in the village of Gokarnaghat, now in the Brahmanbaria, Bangladesh. He was born into a Malo fishing caste, a community whose stories, ethics, and aesthetics served as the foundations of Titash. Mallabarman's positionality was rare in Bengali literature at the time. The critic Drishadwati Bargi says Mallabaran broke the romantic-elitist gaze of the Bengali river novel; and makes the case for Titash as a text of "Dalit consciousness."

For Mallabarman, the novel form and the river mirror one another. Bargi describes Mallabarman's method as that of darader itihas or "compassionate history." Compassion is not only a tone, emotion, or selective principle. It is not about what story is being told or how it is told; but the story itself as a preserving archive. The river is likewise a human archive, a witness to the passage of life. Even as generations are effaced, names are forgotten, homes are consumed, the "deathless" river holds all: memories remain "hidden within the breast of the river" and "written in letters that children cannot practice on paper." The river is a memory-system more faithful than stone or script. Like Marcel Proust, Mallabarman expresses a mystical hope in the imperishability of memories: that lost worlds are never lost but are 'out there,' ensouling the world in matter.

In Titash, all houses lead to the river. Waves intermingle in thoughts. Infants are carried at low-tide and washed with carbolic soap. Fishermen, unaware of the origins of their river, regard it as an eternal fact: a lock of hair in Mahakaal's mythic dance, tracing the frenzied outline of Bengal's rivers. Ecology is not a disenchanted terrain of settlement and mastery. Deities fill the traffic of riverine life. The river binds these pluralities into a single, breathing world: water cosmologies, macaronic folk rituals, the Islamicate and the Vaishnavite. We glimpse what art historian Sugata Ray terms a "hydrosocial imaginary." Titash is thus a window into an indigenous philosophy of flow—a phenomenology of belonging that survives the border, the dam, and the drought.

Mallabarman recalls the world of a pre-Partition Bengal in which Muslims and Hindus were not singularly determined by religious identity. Rather, they shared a society of common custom, language, and belief. Kali Pujo and Muharram are civic festivals. Stories of Karbala and jarigan bring tears to the eyes of Malo villagers; it is the Muslim family of Kader Mian who is enthused above all to participate in the 'nouka baich' or boat race during the pujo season. Many of these social realities became sudden phantoms of the past. Perhaps, Ghatak was attracted to Titash for this reason as well: not simply to stalk a lost personal past, but the forgotten social memories of a divided Bengal.

The novel is filled with poignant descriptions of riverine and human affects intermingling. It leads, at times, to a poetic and anthropomorphic tendency that prefigures the recent legal personhood of rivers in Bangladesh and India:

"Over the water hovers a layer of steam, like pale smoke. [Fishermen] dip their hands and feet in the water under that fog-like steam to feel the slight warmth mysteriously stored there for them, so like the warmth of a mother's body as she sleeps next to her child under the rag quilt."

Economically, fish are at the core of their labouring, imaginative, and metabolic life. Small silvery fish, "ignorant of death," are ecstatic and restless in the nets. Taxes on fish sellers are how Mallabarman introduces hierarchies—of land, caste, and class—that structure and exploit the Malos. Between Malo fishermen and Muslim peasants, there is a moral economy of market ethics, charity, and entitlements; a sense of economic exchange embedded in the social. But society is trampled upon by the resentful Brahmin gentry through debt entrapment, moneylending, land grabs, police and mob violence.

In a beautiful exchange in Mallabarman's novel, two seasonal farm-hands confide in one another. Working all day in the fields—rhythmically chanting Ali, Ali, Ali and Allah, Allah, Momin—the men are provided "rice and catfish curry" by their employer. Instead of relishing their meals, they imagine what meagre dinners their wives are eating back home. With angst, one says: "when I'm eating rice and five things to go with it at the employer's place, I can't help thinking of her. And the food sticks in my throat." They reflect on their wives' hands. One wife's hand is calloused by farm work, the other is full of pin-pricks from sewing. "Her fingers are scarred with a thousand holes and scratches from the needle [...] She's sewing quilts in others' homes, and I feel that needle going through my heart."

Mallabarman's education occurs at a time of radical ferment in Kolkata. Among the thousand or so books in Mallabarman's possession at the time of his death, donated to Rammohan Library, a substantial number of them were Soviet and Marxist literature, ranging from Vladimir Ilych Lenin to Shripad Amrut Dange. The literary critic Bimal Chakrabarty has noted the influence of Soviet literature on Mallabarman's Titash, particularly Mikhail Sholokhov's pastoral-riverine epic And Quiet Flows the Don. In the context of communist, anticolonial, and peasant politics in interwar Bengal, we find aspects of this consciousness in his fiction:

"The landlords are so few because their existence is not genuine—it's only a contrivance. They are the exception among mankind. The real people are the tenants and therefore, at the end of the twists and turns of history, they are recognised as the real owners of the land—not holders of paper claims, but owners of the right to live on it. Similarly, the true owners of the river are the fishermen."

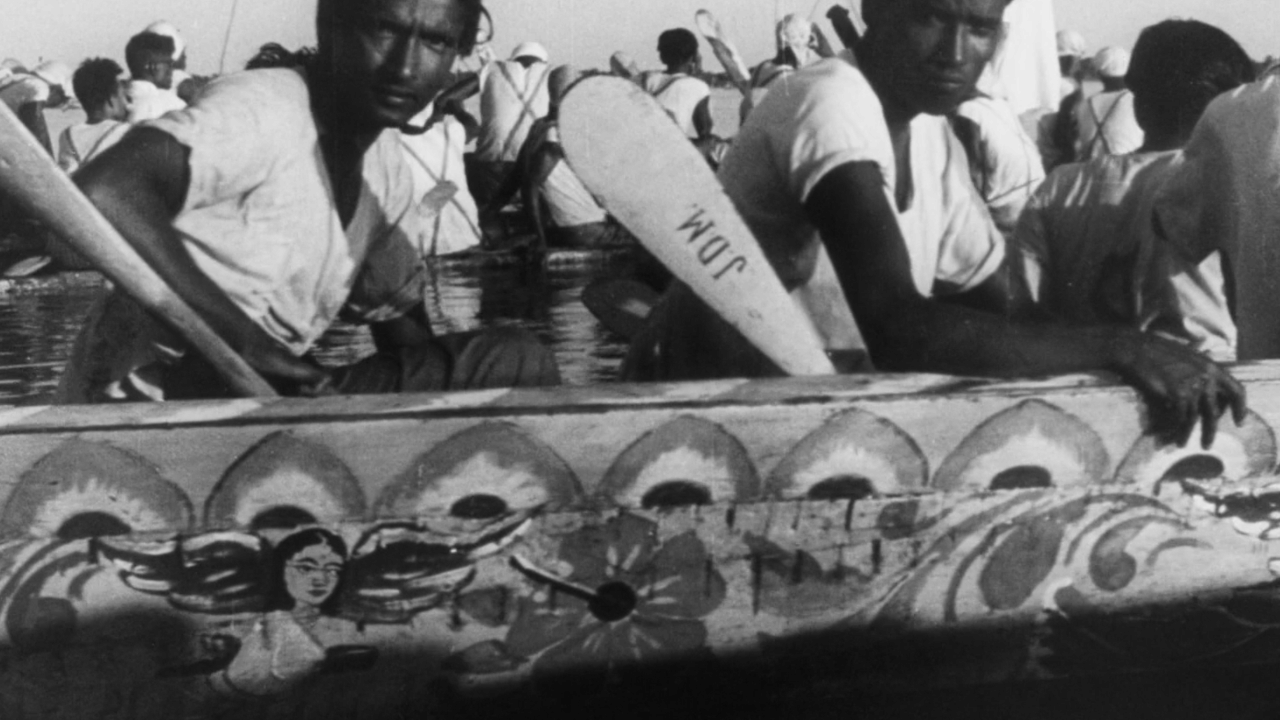

When Ghatak filmed the boat race, his boatsmen and festival-goers were real, riverine survivors of the recent war. Formally, Ghatak translates flux into cinematic rhythm. Water mirrors montage—cuts that dissolve and reform images like currents, surfaces broken by racing paddles. The river's shimmer becomes both screen and subject, an ontological metaphor for film itself: light projected on moving water. His camera lingers on faces, boats, and waves until perception wavers between documentary and dream. Jhumpa Lahiri likened Titash to 'the maritime worlds of Homer,' a fusion of myth and materiality. Ghatak powerfully expresses the Mallabarman's point on Malo identity: those who may own nothing on paper indisputably own the river. Their labour, belonging, but also majesty, make them sovereigns.

III.

This was the world remembered. The novel that evoked these memories and evoked them nearly four-hundred kilometers away. Mallabarman was educated with the collective fundraising of the Malo community. To them he owed not only his life-work, but also his textbooks and school uniforms. By the age of twenty, his two parents, his two brothers, and his sister had passed away. In 1934, the bereft and bereaved Mallabarman left home.

He came to Kolkata. In 1936, he began to work full-time for Mohammadi, wherein he began to publish stories that would ultimately become Titash. One was entitled "The Probashi's Journey"—no doubt, a self-conscious term for himself (probashi, a figure of exile and diaspora). Exile, too, is a fluxive state. It is embodied, as Edward Said listed, as "restlessness, movement, constantly being unsettled, and unsettling others." By 1945, he had fallen on hard times without a stable income. He worked part-time for Desh and, in his free time, transformed his previous instalments into the manuscript for Titash. After great labour, the sole hand-written manuscript of Titash was completed. But, it was soon lost in transit somewhere in the city. Collecting "his broken heart," Mallabarman sat down to rewrite Titash, but now under dire conditions.

As the manuscript for Titash was rewritten from memory, the Partition remade the world around him. Home was now a different country. The announcement of the Radcliffe line intensified communalism. The choice-theories of survival were foisted on those vulnerable groups who would constitute new national minorities in India and Pakistan. It is in this context that the Malos of Brahmanbaria fled to Kolkata as refugees. In ecological terms, as Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal noted, the "division of land and water destroyed the organic river isthmuses that connected Punjab and Bengal to the Indian Ocean." Partition was "a crime against nature and humanity for which the subcontinent is still paying a hefty price."

Mallabarman's friends provided a window into his life at this time. He took on a second job to aid his Malo community in Kolkata. He barely kept himself fed, never married, and lived in a pigeonhole room on the industrial edge of town. Returning home late in the evenings, his body exhausted, he would peer out of his window to see the river of his youth. Gradually, the soot-filled sky would "merge with the pastel skies that leaned over the river of Titash." Mallabarman kept his distance from people. In 1951, he handed his second manuscript over to friends and was hospitalised for tuberculosis. He recovered for a moment, then passed away at the young age of thirty-seven.

IV.

In 1956, the same year Titash appeared in print, Pakistan Shell Oil Company began to prospect over 10,000 square miles of territory in East Pakistan. In half a decade, natural gas reserves were discovered and exploited in the adjoining regions of the Titas River. It was the single largest gas reserve of the eastern wing, a fact of tremendous economic and ecological consequence. After the creation of Bangladesh, these natural gas deposits remained central to the fuel economy of the state, as seen in a 1978 statistic that noted out of an estimated 280,000 million cubic feet of reserves, 225,000 million cubic feet were located in "Brahmanbaria (Titas)." When Mallabarman described the connectedness between human and riverine time; he did not imagine that as Anthropocentric domination, of a temporality defined by hydrocarbons and man as a 'geo-physical agent.'

Partition divided the economic geography of Bengal. The loss of Kolkata, as Tariq Omar Ali has argued, made East Bengal a "hinterland without a metropolis." Consequently, a developmentalist gaze and a vocabulary of 'uplift' was supplied by the Pakistani state. If East Bengal had been "neglected" in favour of Kolkata during the colonial period, Islamabad's state capitalism was to redeem it. Layli Uddin, in her labour history of the Adamjee and Karnaphuli mills, captures the air of "postcolonial ambition" found in the symbols of "industrial and state power." However, it was an ambition that remained more manifest in symbols than in redressing structural inequalities between the country's western and eastern wings. Instead, an extractive economic relationship rendered the East, as some historians have described it, as an "internal colony" of the western wing.

The critique of inequality was a core rallying point for the Awami League and a major part of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's all-Pakistan electoral appeal in 1970. What happened after the failure of state federalism and the democratic transfer of power is well-known: the Awami League won 167 out of 169 seats in East Pakistan, a power-sharing dispute erupted between Mujib, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and Yahya Khan, the army was secretly mobilised, and by the end of March 1971, "Operation Searchlight" was launched in the East, inaugurating what was at once a civil war, a war of national liberation, a Cold War entanglement, and one of the most concentrated genocides of the late twentieth century.

The warless river dreamt by Mallabarman came to an end. Brahmanbaria was a frontier between the Mukti Bahini and the Pakistani military. The district was first under the control of Bengali partisans but an offensive was led by the Pakistani Army from Comilla. The district was the site of aerial bombardments by the Pakistan Air Force and, by the end of April, napalm was reported to have been dropped on several villages. The Pakistani military captured the area through three days of siege and landed in Gokarnaghat, Mallabarman's childhood village. It had been evacuated by freedom fighters and rendered into "a ghost town."

Rivers became nationalist symbols during the war. They evinced the Bengali partisan's intimacy with the terrain. As Moiz Majid noted, the Mukti Bahini fought through "ecologies of emancipation," using waterways as both refuge and weapon. Their mastery of and mutability with nature was taken to furnish their patriotic claim to a geography that often confounded outsiders, a space that James Rennell in 1780 described as "a labyrinth of rivers and creeks." This was in distinction to Pakistani soldiers from the west who were denounced as physical anachronisms. As the Swadhin Bangla Radio across the border broadcasted: "Pakistanis are foreigners in every sense of the term." They were unable to assimilate themselves, physically or mentally, to the unfamiliar landscape of Bengal: "They look physically so different that our boys can spot them from miles."

But this was after all triumphalist, wartime rallying. Rivers also meant wartime displacement, fleeing, fording, drowning, and death. Indeed, 1971 was, in many ways, a war waged within the hydrosphere: a war pervaded by monsoon rains, muddy paths, choleric epidemics, shelled ports, coconut shells as saline pouches, the invention of Orsaline, oceanic supply lines, Pakistani hajj ships repurposed to transport troops, a constant ferrying across of rivers in service of assault and retreat, life and death, escaping and returning to homes.

V.

"Titas has become a tribute to the days that I left behind," stated Ghatak. He was born in 1925 in Dhaka and spent his childhood across Bengal. It was a childhood, as he recounts it, tied to the rivers. He recalls: days spent "on the banks of the Padma," sailors and fishermen, "drizzling rain," "the bells of the sareng," "Muslim peasants dancing and singing with brass anklets," "so many sounds, so many pictures, so much emotion. A civilisation. A flowing stream…"

Titash was the first co-produced film between Bangladesh and India. It expressed a cultural remingling of the two Bengals. Cultural cross-border exchanges were obstructed since 1954, after a tightening of national relations resulting in the inability of Bengali-language films to travel between West and East. In 1965, with the outbreak of war, a full-on prohibition was in place. Ghatak was unable to visit East Bengal, moreover, due to his affiliation with the Communist Party which had been banned under the dictatorship of Ayub Khan.

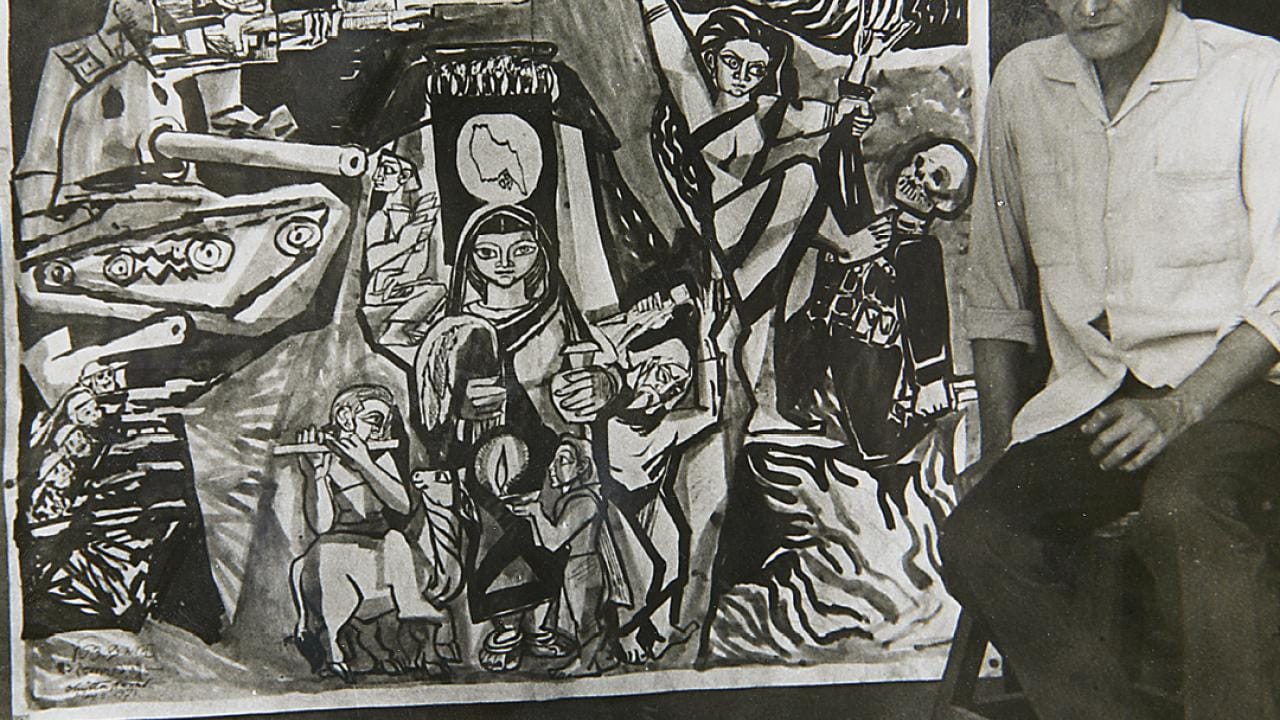

By the time of the Bangladesh War, Ghatak had been in a long-hiatus. His alcoholism, erratic interpersonal demeanour, and sidelining from both the film industry and the Communist Party had negative impacts on his body, mind, and social position. Yet, the war jolted him into action. He responded promptly and passionately, directing a short call-to-action documentary called Durbar Gati Padma. Narrated through a fictional Bengali freedom fighter and the divine-riverine personification of Mother Padma, played by Nargis, the documentary represented the Liberation War through experimental sound techniques, melodramatic expressions, and Eisensteinian montage, including a quotation of the lion statues from Battleship Potemkin. (Like Mallabarman, Ghatak was trained on Soviet forms.) In interviews, Ghatak indicated that he visited the active war-zone across the border and filmed "in the presence of Pak soldiers." Yet, his film represented the violence of the war largely through abstraction and allegory, contrasting the sounds of fighter jets with the lithe poetry of Jibananda Das. His film, moreover, employed a Guernica-esqe painting of the war by the famed artist Chittaprosad.

After the war, Ghatak was invited to the new republic. "When we crossed Padma by air I burst into tears," he recalls. "Satyajitbabu was by my side. I felt that Bengal in plenty and beauty as I knew her years back was still there untransformed." In Dhaka, the two titans of Bengali cinema commemorated Shaheed Dibosh in honour of the Bengali language martyrs of 1952. Throughout his first visit since Partition, Ghatak described a "child-like feeling that time stood motionless there […] Out of this childlike simplicity, Titas originated." After the war, paper was scarce. In a passionate haste to begin his work—as an apocryphal anecdote states—Ghatak began to write the script of the film on his shirt. Someone intervened and provided him, instead, a starched white saree.

Ghatak often figures as a shorthand for the Partition, an exemplary 'artist-as-sufferer.' Partition was, indeed, the catastrophe of his art. Yet, to reduce Ghatak to only displacement and melancholia is to forget his cinema is equally about belonging and revolution. Not delimited to India, Ghatak was an internationalist and insisted that if the "Bengali nation" died, he would not wish to live. Titash is the venture of the returnee, not simply the refugee; a project that restored Ghatak to the world of the living. Herein, Bangladesh was not merely a nation-state but the name of a long-lived cultural continuum united by rivers: "The Padma, Yamuna, Ganga, Shitalaksha, Dhaleswari, Brahmaputra, Kushiara, Teesta, Surma, and Titas…"

VI.

Slowly, his feelings dissolved into estrangement. At the Press Club in Dhaka in March 1972, Ghatak expressed the alienation around him in the East. Dhaka's simplicity has vanished and the city has become a "raging river." In translating words, memories, and traces into corporeal images—transposing the past onto the present—Ghatak found himself dejected by the reality around him. He found himself in the midst of ruins and fragments, a landscape where nothing of the personal past remained. It was a landscape of physical debris as well: a space of recent total war, scarred by American munitions, vacillating between hunger and hope. He provided scant answers to political and economic questions, stating that his "thoughts on markets were worthless." He is here, above all, "to visit [his] motherland." His films are for people, as "Eisenstein and Pudovkin did." He wished that Titash could, one day, be exhibited village to village.

Titash was financed by an eccentric, inexperienced, young Bangladeshi producer named Habibur Rahman Khan. "I have never seen such a boy," recounted Ghatak: "I will give money. Ritwikda will create a film [and] I will enjoy it sitting in an air-conditioned hall. It matters little whether money invested is recovered or not." This boyish, non-commercial attitude was affirmed in a later interview by Khan himself, who described his adolescent fascination with film magazines: "While discussing art films with my classmates, although they used to emphasise Satyajit Ray, I realised that [Ghatak] is a filmmaker who thinks of films the way I do. The funny thing is that I agreed to produce a picture with him without seeing any of his pictures."

Ghatak was frustrated by the material underdevelopment of the Bangladeshi film industry. "[Y]ou would touch the sound machine [and] it would break into pieces," he recalls. In its time as a Pakistani industry, Dhaka had one film studio whereas the western wing had nine. "Only a lunatic or an ass would try to make a film in that country," he would later state, "and I was both." Yet, despite these technical challenges, Ghatak's artistry benefited from being enveloped in the eastern countryside. Khan recalled seeing the director shooting on location: Ghatak paused the shoot to wet his hands in the river and pressed them to his face; as if to "deepen the feeling" of the river in him.

Yet, Ghatak's embodiment in nature also proved hazardous. Combined with his ill health, the demands of the film hospitalised Ghatak. From Dhaka, he was flown back to Kolkata. Unable to complete the film, he provided instructions to his crew from his sick bed. He did not even see a rush print. Despite Ghatak stating that he "systematically" explained the film, the Dhaka crew that formed the final cut of Titash made decisions as creative as they were rote. The precise point of cuts, the arrangements of cinematic form; these were given their textural shape by the crew and one may note a general proclivity in Titash toward shots that perhaps lingered a touch longer, montage with more air.

From his hospital bed in Kolkata, Ghatak was interviewed once more. His difficult time in Bangladesh was over and disillusionment lingered. "History has destroyed all the beautiful things that existed before," he said. In pursuit of his pre-Partition childhood, he returned unable to "trace the pastness of this place." Perhaps, Bangladeshis also felt this way after the war. In an article entitled "Ritwik Ghatak: A View from Bangladesh," the leftist filmmaker Alamgir Kabir expressed his disappointment in Ghatak's statements, from the earlier "lunatic or an ass" comment to Ghatak's lack of appreciation of the resources his fledging, impoverished country provided him. Yet the core of Ghatak's disillusionment was philosophical rather than political. His quest for a lost unity revealed history to be an irretrievable, onward catastrophe. Flux is a series of historical ruptures and reassemblies; herein, Ghatak differs from Mallabarman, for whom no memory is truly ever lost despite the shifting of forms.

At the Dhaka premiere, his note praised his Bangladeshi crew, who transformed absence into collaboration. Like Mallabarman's friends preserving his manuscript, they kept the dream alive. Both novel and film survive through collective care. Derek Walcott, on viewing the Ramleela in Trinidad, wrote: "Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole." Such is the story of Titash and much of twentieth century Bengali art: mendings after shatterings, reparative memories of love after the 'unbearably secular' mutilations of history.

Ghatak worked again with the cinematographer Baby Islam for his final film, Jukti Takko Gupto. He was said to have pitched another cross-border production, but after the 1975 coup in Bangladesh, such a film would not have been feasible. Ghatak passed away in 1976 at the age of fifty.

VII.

A. K. Ramanujan's poem "A River" observes that poets praise the Madurai river when abundant and flooded but flee its dry season, when it reveals its unpleasant "ribs" and "hairs." Thus, "the river has water enough to be poetic about once a year." Romantic tradition does not permit us to see its ambiguities, its grotesques, its drowned. Ghatak's ending resists such blindness; he confronts the aesthetics of desiccation, the moral imperative to see what tradition overlooks.

In both novel and film, the river's desiccation signals the end of a world. An 'augering of the future,' as Naveeda Khan puts it. Mallabarman's villagers sense subtle shifts—currents bent, fish migrating, silt rising—until their homes become unmarked graves. Ghatak transforms this natural process into myth. A vast desert emerges where a river once flowed. It is a vision of planetary death. Yet, Ghatak's apocalypse carries the seed of renewal. "Adwaitababu has done the natural. He ends it in ruins; everything is shattered down," says Ghatak. "My hint at the end is at the new order, the new life that is struggling to be born. You may call it Marxism, or you may not see any political view in it […] human civilisation is deathless." This is unlike the pessimism of Partition melancholia, a Ghatak of pyrrhic humanism. The last shot is, consequently a mirage of a running child, an affirmation of continuity within extinction.

In "fictions of the End," water is a recurring spectre. One thinks of Gilgamesh, the Biblical flood, even Ishmael's discourse in Moby Dick on the "universal cannibalism of the sea." But the eschatology of Titash is not abundant waters or the flood myth, but the disappearance of water. Yet, like the world-flood, it is still an eschatology about the faintly-held-together equilibrium of the world that allows human life to exist in the first place.

In breaking the model of the flood, desertification brings about its own imagistic associations—particularly, in Ghatak's film, released in Bangladesh in 1973. The construction of the Farakka Barrage, which threatened the distribution of Gangetic water flows, led to one of the largest protests in the post-independence decade. Maulana Bhashani, the then 95-year-old peasant leader marched to the Indian border in 1976, the year of Ghatak's passing. The immediate aftermath of Farakka was the desertification of 54 rivers in Bangladesh. Today, anthropogenic climate change, moreover, makes Bengal one of the most hazardous frontiers of rising sea-levels. The pain of water was never a metaphor.

In Titash, we encounter a curious yet foundational humanism in the eschatological, or that which Frank Kermode suggested in his rhetorical question: "what human need can be more profound than to humanise the common death?" Indeed, the river of eventual lapse and tragedy in Mallabarman's novel is, for the people who once lived on its shores, also a name that hangs like "a garland around their necks."

Mahdi Chowdhury is a writer, researcher, and doctoral candidate in History at Harvard University. He has previously written for Asia Art Archive, The New Inquiry, and Jadaliyya.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments