The lost history of Pilkhana’s elephant depot

What is today a bustling capital once stood on the brink of desolation. In the seventeenth century, Dhaka was among the most prosperous cities of eastern India, home to nearly nine lakh people. But after the capital shifted to Murshidabad in 1704, famine, drought, epidemics, and neglect steadily eroded its grandeur. By 1872, only sixty-nine thousand inhabitants remained. Once-vibrant quarters like Narinda, Wari, and Azimpur lay abandoned, while disease and decay haunted its canals and cantonments. Amid this decline, a curious revival took shape—the Hathi Kheda enterprise, the organised capture of elephants, which briefly restored Dhaka's fading significance.

Hunting the elephant, not shooting

To the British authorities of the nineteenth century, 'hunting' was more than sport—it was prestige and power. Among the big game, elephants stood as the ultimate prize, pursued through elaborate expeditions. In colonial records, elephants were "hunted," rarely "shot"—for hunting implied a ritual of mastery, where the elephant was subdued through courage and strategy rather than killed outright.

Origin of the kheda system

In the 1770s, the East India Company renewed its attention to kheda expeditions. The objective was to replace bullock carts in military transport with the stronger and more versatile elephant, which could be employed in both logistical and combat operations. Although the use of firearms, cannons, and gunpowder was rapidly expanding during this time, the elephant retained strategic importance across the subcontinent—especially in frontier expansion and expeditions through difficult terrain. Under such circumstances, bringing the vast and free-ranging elephant population under the exclusive control of the colonial state became an urgent necessity.

The British learnt much from the Mughals in matters of elephant management. The refined systems of training and upkeep developed during the Mughal period for warfare and ceremonial use influenced both regional kingdoms and the later British administration. Among the traditional methods of elephant capture were the pit trap, the noose or mela shikar, and the wooden stockade known as the kheda. Under British rule, these methods were re-evaluated. For safety and humanitarian reasons, the pit trap was completely banned in territories under direct British administration, though it continued in some princely states. Gradually, mela shikar too was phased out. In the British view, the kheda was the most controlled, effective, and comparatively humane method.

The Dhaka kheda office and life at Pilkhana

In 1810, the British established the Military Commissariat in Bengal—a department responsible for the supply of military provisions. One of its key functions was the procurement and maintenance of elephants for the army. From this necessity emerged the Dhaka Kheda Office. Geographically, Dhaka was ideally situated—only about two hundred miles away from the forested hills of Chittagong, Sylhet, Tripura, Cachar, and Assam, regions teeming with wild elephants. Moreover, as a centre of the elephant trade, Dhaka offered cost-effective and efficient logistical advantages for conducting kheda operations.

Additionally, there had long been an international demand for ivory artefacts, and during the colonial period this demand expanded further, boosting Dhaka's ivory industry.

Under the Kheda Office, the captured elephants were supervised by a European superintendent, under whom worked local contractors and skilled kheda workers. Every year, the kheda expeditions began in December and continued for three to four months. By May, the captured elephants were brought to the Dhaka depot. There, with the assistance of kunki (female) elephants, the wild ones were trained until November. Upon completion of their training, they were sent to the military depot at Barrackpore, from where they were distributed to various commissariat stations across the country.

The kheda expeditions for capturing elephants were extremely labour-intensive and expensive. Usually, in November, a reconnaissance team known as the Panjali was sent out first to locate the habitats and migration routes of wild elephants during winter. This group comprised about sixteen men, assisted by another eight labourers responsible for carrying their food and equipment. Once a potential hunting ground was identified, around three hundred garua (field hands) were dispatched to encircle the entire area. Among them were twelve sardars (leaders), while each group of twenty-five garua worked under the supervision of a dafadar and a barkandaz (guard). The entire expedition was led by a superintendent. Only the jamadar and a few senior officials were employed on a permanent basis, while coolies and labourers were hired on short-term contracts, typically for two or three months each year as needed. The work involved considerable risk—many participants lost their lives during the expeditions. Yet, there was never any shortage of volunteers.

Because of the high costs involved, the Dhaka Kheda Office had not become profitable even by the late 1850s. Eventually, in 1862, the government decided to suspend the official kheda operations temporarily in order to reduce expenses. However, private initiatives failed to capture elephants in sufficient numbers, prompting the authorities to reinstate the government-run kheda in Dhaka in 1865. Valuable accounts of this period's elephant-management system are found in Principal Heads of the History and Statistics of the Dacca Division (1868) by Arthur Lloyd Clay, the then Joint Collector of Dhaka. He wrote that, at the time, there were no elephants under government ownership in Dhaka city. However, thirty-four elephants were registered under the names of local landlords and European planters within the jurisdiction of the Sadar police station. Although the government elephant depot had remained unused for a long time, efforts were later made to revive it.

Professionalising the kheda department

It was G. P. Sanderson who gave the Dhaka kheda office a professional shape. In September 1875, he was appointed Superintendent of the Dhaka kheda department. Residing in Dhaka for a long period, he restructured the entire system through modern hunting techniques, efficient administrative procedures, and a well-organised commercial framework. The economic aspects of the kheda operations under his supervision are reflected in the advertisements for elephant sales published in contemporary newspapers. For instance, The Hindoo Patriot of 15 May 1882 carried a government notice for the sale of elephants, signed by Sanderson himself. Even earlier, on 31 March 1870, Amrita Bazar Patrika had printed a similar advertisement announcing the sale of government elephants in Dhaka—evidence of the continuity of this commercial enterprise.

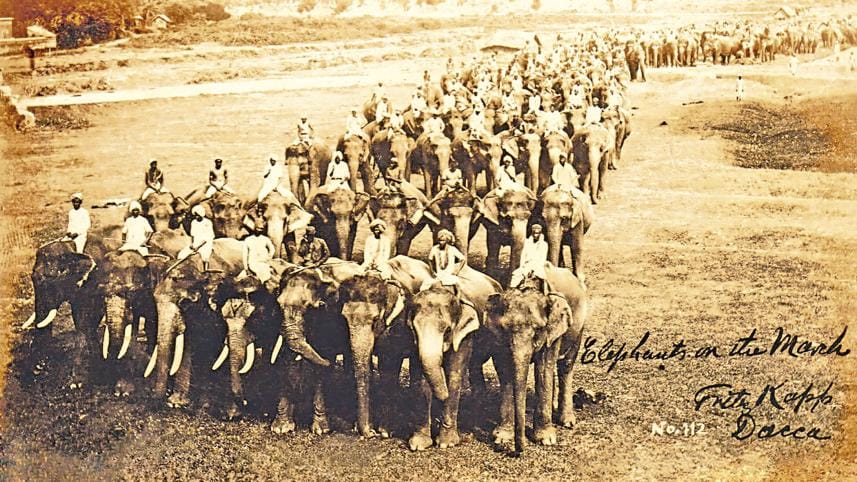

Pilkhana: The elephant depot of Dhaka

The Kheda Office was commonly known as Pilkhana (literally "elephant enclosure"). In his book Glimpses of Old Dhaka, S. M. Taifoor recounts that at one time Pilkhana was an open field on the western edge of the city, close to the river—a site later used as the headquarters of the East Pakistan Rifles. During the nineteenth century, private landlords could also keep their elephants there by paying a prescribed fee. As Pilkhana remained under the direct control of the central government of India, its European supervisors often showed reluctance to follow the orders of the provincial administration.

The depot's proximity to the river made Pilkhana an ideal site for elephants. Bathing and watering them was convenient, and fodder could easily be delivered by boat. The collection of grass for elephant feed developed into a distinct business. Local boatmen and grass-cutters, after paying rent and obtaining permission from landlords, harvested grass from the marshlands and supplied it to the Kheda Office.

In his autobiography Thirteen Years among the Wild Beasts of India, Sanderson painted a vivid picture of Pilkhana. According to his description, the depot covered nearly one-quarter of a square mile and was surrounded by a moat. Inside, rows of brick-paved stalls with wooden posts were used for tethering elephants. There were long sheds to provide shade during the summer heat, a separate hospital for sick elephants, storerooms for food and equipment, and a warehouse for howdahs and ropes. Even a local physician was employed to attend to the mahouts. At that time, Dhaka was the principal centre in Bengal for the supply of elephants used in government service.

Elephants and the city

However, the movement of elephants within the city posed significant challenges for municipal authorities. Just before the formation of the Dhaka Municipality in 1864, members of the Dhaka Committee brought this issue to the attention of the visiting Lieutenant-Governor, describing it as a major public nuisance—an incident recorded in A City and Its Civic Body, edited by Azimushshan Haidar.

The present-day Elephant Road was originally the main route for elephant processions. In Nawabganj, a jetty constructed for the elephants of Pilkhana is still known as Hatir Ghat ("Elephant Jetty"). Likewise, the name Hatirpul ("Elephant Bridge") originated from a high bridge under which elephants used to pass. The bridge was built with extra height to accommodate their towering frames, and from that unique feature the area derived its enduring name—Hatirpul.

Dhaka's elephant kheda and the lives of the mahouts

The mahout—caretaker, trainer, and physician of elephants—led a life filled with toil on one hand and constant danger on the other. A vivid account of the mahouts of Dhaka during the nineteenth century appears in James Wise's Notes on the Races, Castes and Trades of Eastern Bengal (published in 1883). His description reveals that most mahouts employed at the Government Kheda Office were Muslims, generally from lower-caste families. Within their profession, titles such as Jamadar and Sardar were customary. According to Sanderson, the Superintendent of the Dhaka Kheda Office, the mahouts, through long experience, became remarkably skilled in determining the exact age of an elephant. Trained elephants were said to grow so fond of their mahouts that their attachment often surpassed their loyalty to the owner; even after years of separation, they could recognise their mahout instantly.

The colonial-era book Oriental Field Sports by Williamson also noted the extraordinary proficiency of native mahouts in the care and treatment of elephants. For instance, when elephants suffered from intestinal worms, they would feed them water mixed with rock salt; and when the animals' feet became sore from walking on dry or stony terrain, they would treat them with herbal remedies. The mahouts' residential quarters in Dhaka too earned a separate identity—the area where they lived became widely known among townspeople as Mahuttuli.

From private enterprise to state control

Before 1857, the army's need for elephants was largely met by private owners. In the early nineteenth century, although the Dhaka administration participated in kheda operations, the work was entirely dependent on private initiative. However, by the mid-century, the British government brought these activities under state control, establishing a monopoly over elephant hunting. The Forest Act of 1878 and the Elephant Preservation Act of 1879 placed wild animals—especially elephants—under the British government's strategic control and usage. Yet debates surrounding the government's exclusive right to capture elephants on public land had begun much earlier, as far back as 1851.

During the 1860s, the British established monopoly control over the elephant trade across India, ensuring hunting rights through a system of government khedas and leases. With the rapid decline in the elephant population and their growing nuisance in rural areas, an effective conservation policy was framed under Sanderson's leadership. Its aim was to meet the military and strategic requirements of the state while safeguarding the lives and property of local inhabitants. Similar policies were also introduced in southern India to prevent indiscriminate hunting, creating a new framework that combined conservation and control.

Alongside government-run khedas, hunting rights in certain forests were leased out, on the condition that a specific portion of the captured elephants—usually those above a certain height—had to be handed over to the state. In practice, however, the lessees often violated these terms, resulting in revenue loss for the government, and penalties were seldom enforced effectively. This irregularity weakened administrative control on one hand, while on the other, it created a constant tension between central directives and local autonomy.

Landlords, meanwhile, considered government interference oppressive, though they did experience some relief as wild elephant incursions diminished. Nonetheless, many landlords took the issue of hunting rights to court. In the Garo Hills, landlords' privileges of hunting and collecting revenue were revoked, and obtaining a licence became mandatory for any hunting expedition.

Through the intertwined systems of hunting and forestry management, the colonial administration built a strategic bridge for the control of natural resources. In this process emerged a dual framework of conservation and exploitation—where the elephant became an inseparable component of political, economic, and military strategy. The so-called "preservation laws" served as the legal foundation of this control, enabling the British to consolidate their monopoly over elephant hunting, trade, and training.

Hossain Muhammed Zaki is a Researcher. He can be contacted at zakiimed@gmail.com The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments