Sher-e-Bangla and his political rivals

In the 1946 elections, the Muslim League in Bengal overwhelmingly defeated all other Muslim political parties. Yet it must be noted that before 1947 the League was not the sole major political current among Bengali Muslims. Two entities in particular require mention: the Khilafat Movement and the Krishak Praja Party.

From the end of the First World War until about 1925, the Khilafat Movement was the most important socio-political movement among Bengali Muslims. In the next phase the Krishak Praja Party gradually emerged as a party and the Muslim League was also revived. The rise of the Krishak Praja Party in 1936 was a particularly striking chapter in Bengal's Muslim politics. This party addressed Bengal's socio-economic demands and incorporated non-Muslim interests in a substantial way.

During the Khilafat Movement Indian Muslims argued that Britain should side with the Ottoman Caliphate, since India had a large Muslim population. Mahatma Gandhi lent his support to the Khilafat Movement and successfully linked it to his anti-colonial satyagraha campaign. A.K. Fazlul Huq also played an organising role in the Khilafat movement.

Kolkata was a key provincial centre of the Khilafat Movement. The office of the organisation was located there. Here Huseyn Suhrawardy, returning from London, joined the movement near the end. He served for a time as secretary of the Calcutta Khilafat Committee.

Although the Muslim League was expected to play a leading role in the Khilafat Movement, its central leaders remained aloof. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in fact, opposed the movement.

After 1924, the Khilafat Movement gradually declined in India, but by then it had already produced a new generation of political workers and organisers among Bengali Muslims. These men became the organisational strength of the Krishak Praja Party and revived the Muslim League.

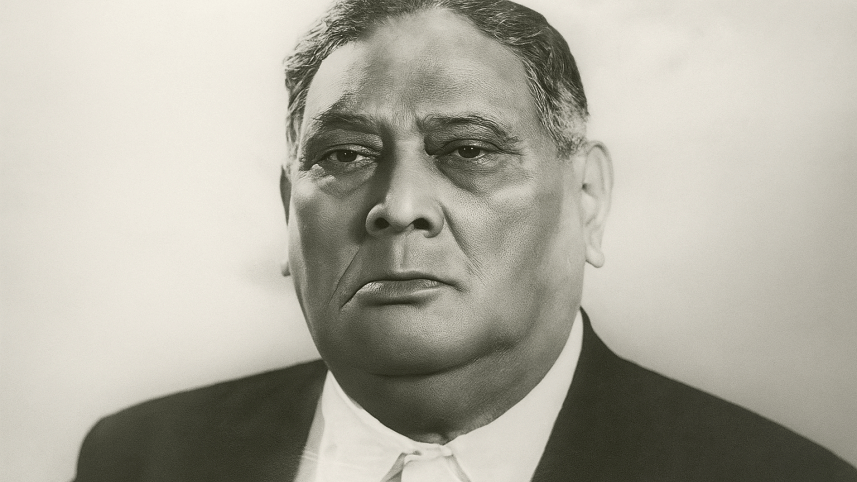

The All-Bengal Praja Association's Fazlul Huq

In 1920–21, while Suhrawardy was engaged in organising the Khilafat Movement, Fazlul Huq was active in the Barisal region of Bengal, holding mass meetings on agrarian and land issues. In this way the foundation of his future party, the Krishak Praja Party, was being laid. At that time he and his associates worked under the name the All‑Bengal Praja Association (Nikhal Banga Praja Samiti). Its president was Sir Abdur Rahim and their base was at 92 Ripon Street, Calcutta, where on July1, 1929 the Praja Association was formally established.

When the association was founded, Fazlul Huq became vice-president; Akram Khan was general secretary. Among the vice-presidents was Abdullah Suhrawardy, maternal uncle of Huseyn Suhrawardy. The significance of Suhrawardy's participation, despite neither he nor his family being landlords or peasants, was that the 'Praja' (tenant/peasant) mobilisation fit what a portion of the Muslim leadership saw as a more constructive strategy. Since many tenants (praja) were Muslim and their socio-economic adversaries mostly non-Muslim zamindars (though Muslim ones also existed, fewer in number), the "praja-mobilisation" appeared a viable alternative to communal Hindu-Muslim politics. It could also be read as a new kind of class politics. The Praja Association's slogan was: "Land belongs to the one who ploughs."

In 1925 the death of C.R. Das and, a year later, widespread communal riots in Calcutta triggered fresh communal polarisation in Bengal. The nascent organisers of the Praja Party began to raise demands for Muslim tenants in the field. The long-term fruit of this was the emergence of the Krishak Praja Party by about 1936. After the 1937 election the party emerged in Bengal as the principal organisation of the Muslim community. Its assemblies even included many Namasudra [historically under-privileged] peasants.

The political partnership between Fazlul Huq and Syama Prasad Mukherjee was a remarkable episode in Bengal's politics and held significance for India's future as well. It proved that Hindus and Muslims were capable of forming a government together anywhere in India.

Among Bengali Muslims at this time some Khilafat activists joined the Krishak Praja Party, others joined the Muslim League. Suhrawardy became the standard-bearer of the latter. Fazlul Huq, along with Maulana Moniruzzaman Islamabadi, became leaders of the former trend.

Why Suhrawardy chose to join the League instead of the Praja Party can be partly explained by his shifting outlook after the 1926 riots. His thinking increasingly centred on the question of political power for India's Muslims. In other words, a communal turn had taken place in his political outlook.

However, Muslim-majority parties other than the League were still trying to survive by keeping a distinct identity. They sought to pursue Muslim ambitions within a united India framework. That is why they are often described as "nationalist Muslim" parties. In 1944 at Delhi and at Calcutta two all-Indian conferences of Muslim Majlises (councils) took place, an initiative in which Fazlul Huq participated. In preparation for the 1946 election they attempted to build a structure called the "Nationalist Muslim Parliamentary Board", in which Fazlul Huq's KPP played a role alongside Jamiyat-ul-Ulema, Anjuman-e-Watan and the Mumin Conference. That is to say, the Fazlul Huq whom we always regard as the politician of Bengal's peasantry had, in fact, made several attempts to intervene in central politics as well. The Deobandi ulama under Maulana Madani also gave degrees of support. But this alliance failed to stop Partition.

The Bengali version of this failure can be seen in the short-lived joint provincial government of Fazlul Huq with Syama Prasad Mukherjee.

Syama Prasad & Fazlul Huq: A meaningful but fleeting alliance

In the elections of 1937 and 1946 although Syama Prasad Mukherjee was a member of the provincial Legislative Assembly, it was under the indirect support of the Congress at the University of Kolkata seat of Graduate electors where he stood unopposed. His party, Hindu Mahasabha, in Bengal secured 2 seats out of 250 in 1937 and 1 seat in 1946.

In the years leading up to 1947, northern Indian influence largely shaped Bengal's political trajectory, and only a handful of Bengalis resisted this dominance—most notably Suhrawardy and Syama Prasad Mukherjee. In the intervening decade between the 1937 and 1946 elections one can observe Suhrawardy and Mukherjee in opposing political positions.

In 1941 Syama Prasad drew near to Muslim politicians for a while. Fazlul Huq was then serving as Chief Minister of Bengal. In dispute with the League he formed a second term government in alliance with the Hindu Mahasabha, sometimes referred to as the "Progressive Coalition Ministry" or "Huq–Mukherjee Cabinet".

Sarat Bose was one of the key figures behind the original plan to form that coalition government. He was supposed to serve as the Home Minister. Had the government not arrested Sarat Bose, it would have been known as the Huq–Bose government.

The political partnership between Fazlul Huq and Syama Prasad Mukherjee was a remarkable episode in Bengal's politics and held significance for India's future as well. It proved that Hindus and Muslims were capable of forming a government together anywhere in India. The Krishak Praja Party also demonstrated that such cooperation was possible not only with moderates like Sarat Bose, but even with the Hindu Mahasabha. What made this coalition particularly striking was that Fazlul Huq, who had moved the Lahore Resolution in 1940 advocating separate Muslim states, was nonetheless able to form an alliance with Mukherjee and the Hindu Mahasabha.

In the charged communal atmosphere of the time, the Huq–Syama coalition government was a positive development. Even so, it was not unusual for the Muslim League to oppose the government led by Fazlul Huq. In fact, the League reacted fiercely, making Fazlul Huq its principal target. Jinnah virtually declared war against him, while Suhrawardy, Nazimuddin, Isphani, and Akram Khan carried that battle into the villages. The British administration, too, took deliberate measures to weaken the coalition.

The Huq–Mukherjee coalition stood little chance of survival under the twin pressures of the League and the colonial administration. Unsurprisingly, the government proved short-lived.

After the 1936 election in Bengal, Fazlul Huq formed the province's first government through the Krishak Praja Party. When the Muslim League withdrew its support and the fall of the Huq Ministry seemed inevitable, Syama Prasad Mukherjee stepped in to help sustain it. That act alone marked him out as an adversary in the eyes of the League. Moreover, Mukherjee's Hindu-oriented policies clashed with the League's advocacy of Muslim interests. This tension gradually evolved into the Mukherjee–Suhrawardy rivalry, bolstered by Congress support. By 1947, Mukherjee had come to be viewed in Bengal as the chief defender of "Hindu interests," while the League positioned itself as the champion of Muslims. In this polarised environment, Huq's centrist politics steadily lost their appeal.

Although Fazlul Huq was actually the primary opponent of both League sub-factions, the most aggressive efforts to sideline him and remove him from the Chief Minister's office came from Suhrawardy. This escalation began after 1941 when Huq's relationship with the League was severed.

Fazlul Huq – Suhrawardy: A self-destructive rivalry

In the politics of Bengal among Muslims the role of the individual has always been a crucial element. Accordingly, in the mid-20th century Bengal Muslim League's development featured two sub-factions. One, the "Calcutta Group" led by Suhrawardy; the other the "Dhaka Group" led by Khaja Nazimuddin. These two sub-groups symbolised different socio-economic interests: the former representing the rising middle class within the League, the latter representing wealthy landlords and zamindars. Although these two groups were constantly embroiled in intra-party struggle, their common political adversary was Fazlul Huq. In the list of Hindu politicians, Syama Prasad was the main opponent of both factions of the Muslim League.

When Fazlul Huq and Syama Prasad formed a coalition government, it naturally sparked a firestorm within the League camp. However, it was Fazlul Huq, not Syama Prasad, who suffered the most from that blaze.

The rivalry between Fazlul Huq and Suhrawardy had partly familial roots. Suhrawardy's father-in-law and Fazlul Huq together founded the All Bengal Praja Samiti. In 1934, when Sir Rahim stepped down as president of the organisation, he overlooked Fazlul Huq's claim to the position and instead named Khan Bahadur Mumin of Burdwan in West Bengal. This led to a dispute between Huq and Rahim, and as a result, the Huq-backed faction of the Praja Samiti began operating under the name Krishak Praja Party in 1936.

Although Fazlul Huq was actually the primary opponent of both League sub-factions, the most aggressive efforts to sideline him and remove him from the Chief Minister's office came from Suhrawardy. This escalation began after 1941 when Huq's relationship with the League was severed.

It is worth noting that, at the time, it was possible to be associated with multiple parties simultaneously. Huq was often involved with both the League and his own party at the same time.

By September 1941, Huq's relationship with Jinnah had deteriorated. Following his expulsion from the League in December, Suhrawardy was soon seen rallying public opinion in Calcutta against him. In 1943, Suhrawardy finally succeeded in driving Fazlul Huq from power. Interestingly, the two men were distantly related by marriage—Suhrawardy's maternal uncle, Hassan Suhrawardy, had married the sister of Huq's first wife. Yet, as events proved, political ambition outweighed kinship.

At that time the British Raj increasingly began to recognise only the Congress and the Muslim League as representative all-India forces. Faltering beneath that marginalisation, Fazlul Huq's centrality in Bengal politics declined from 1944 onward. Direct evidence of this is the 1944 Calcutta Corporation election — no candidate nominated by Huq succeeded.

In 1944, even when politically cornered, Fazlul Huq continued his efforts to unseat the League's Nazimuddin Cabinet and finally succeeded in March 1945. However, he did not directly benefit from this success, as Bengal's administration remained under the Governor's control until the new elections of 1946.

An interesting aspect of this period is that Fazlul Huq was also in contact with Jinnah, seeking to return to the Muslim League. Eventually, in September 1946—after the elections—he managed to rejoin the very party he had left in 1941. By then, however, the Bengal Provincial Muslim League had come under the control of the Suhrawardy and Abul Hashim group. The nomination board formed ahead of the 1946 elections was dominated entirely by this faction.

After the 1946 election, when Suhrawardy became Chief Minister, politics and society in Bengal were being reshaped. The British Raj's negotiations with the Congress and League over the Partition of India had deeply absorbed the local society; the 1946 riots added fuel to this trend.

At the same time Fazlul Huq was discussing, at various levels, a concept of an all-party government in Bengal. As part of that he met Gandhi at Haimchar (now Chandpur) on February 27, 1947. Yet everyone, including Gandhi, knew Huq was no longer the driving force of Bengal politics. He was in Calcutta at the time of the riots. But the focus of communal violence diverted attention away from him. The League considered him a "fifth column".

When the vote was cast in the provincial council in June 1947 on Bengal's geographic future, Fazlul Huq was wholly absent — a striking fact. He took no major initiative to prevent Bengal's partition, which remains surprising.

When Partition of Bengal was virtually assured and mass refugee movements began from both sides, it was only on August 1, 1947 that Fazlul Huq came to Barisal and urged Hindus not to leave.

It was during this tug-of-war over Bengal's partition that the long separation between Suhrawardy and Fazlul Huq occurred. We would see them again on a same platform when the United Front (Jukto Front) was formed in East Bengal in 1954. They were able to return to politics in the newly formed Pakistan, which stands as proof of their own political strength and popular support.

Half a century later, in a 2004 survey by the BBC asking for the greatest Bengali person of all time, both Fazlul Huq and Suhrawardy were ranked among the top twenty: the former coming fourth and the latter twentieth.

Altaf Parvez is a researcher specialising in history. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments