Sandwip’s forgotten wars

We now arrive at the final chapter in Sandwip's story — the concluding instalment of the three-part series on the island's forgotten history, published in the In Focus section of The Daily Star.

Arakan attacked the Portuguese at Dianga in 1607, and Manuel de Matos, ruler of Sandwip, went across to render help, leaving Pero Gomes in charge. Matos died in the siege of Dianga.

Muslim Port: 1607–09

Gomes was a hopeless administrator, unpopular both at Sandwip and in Goa and Lisbon. He was so incompetent that Lisbon suggested Viceroy Dom Francisco d'Almeida directly administer Sandwip from Goa. In this messy situation, Gomes' employee Fateh Khan seized Sandwip and declared himself ruler with a mission.

His flag proclaimed: 'Fateh Khan, by the grace of God, Lord of Sandwip, shedder of Christian blood and destroyer of the Portuguese nation'. He had the 30 Portuguese traders of Sandwip, their families, and native-born Christians killed. Along with his army of 'Moors' and Pathans, he created a fleet of 40 boats, which he maintained with Sandwip's revenues.

Fateh Khan's fleet circled the area looking for the survivors of the Dianga massacre. They were found on Dakhin Shahbazpur island (present-day Bhola). The survivors had become pirates, led by Sebastião Gonçalves y Tibau and his jalia commander, Sebastião Pinto.

As Fateh Khan's 40 ships and 800 men were about to attack, Gonçalves counterattacked with his force of ten ships and 80 Portuguese men. The battle raged on until morning, when it became clear that Fateh Khan lay dead and his entire force had either been killed or taken prisoner. Without sanction from Goa or Lisbon, Gonçalves and his freebooters seized Sandwip in 1609.

In this troubled situation, Min Razagyi of Arakan offered Sandwip to the Dutch, but they refused. Lisbon stayed aloof and did not support Filipe de Brito de Nicote's offer to take over Sandwip, thinking the island had been given to the Dutch. This was made clear in the letter of February 20, 1610 from Portugal's king to viceroy Ruy Lourenço de Tavora.

There was no Mughal presence. Although Man Singh had made Dhaka his base in 1602 in order to further Mughal advance in southeast Bengal, and it became the provincial capital in 1608, the Mughals had no policy towards the informal Portuguese empire in the Bay of Bengal. They did not interfere in the matters of 1607 and 1609. Their sole goal was to resist Arakanese expansion from a central point, but here too Mughal policy was erratic.

In 1615 a Dutch-Arakan force beat Gonçalves at Mrauk U. In 1617 Min Razagyi's son and successor, Min Khamaung, attacked Sandwip and defeated Gonçalves once and for all. Busy confronting the delta's rulers—the baro bhuinyas—the Mughals did not feature in these campaigns. They stepped into the picture only after 1617 when Min Khamaung defeated Gonçalves. By then, two of the baro bhuinya, Kedar Rai and Pratapaditya, had abandoned all claims to Sandwip. The Mughals gave the island to Min Khamaung as jagir; from then on it remained in Arakan's possession, with nominal suzerainty to the Mughals.

A Pirate Port: 1609–11

When Min Razagyi attacked in 1607 some of the Portuguese escaped by boat. One such was Sebastião Gonçalves y Tibau, a salt merchant who had arrived at Dianga through the Meghna River just before the attack.

Gonçalves defeated Fateh Khan's forces in 1609 in alliance with Pratapaditya of Bakla, who held a string of ports in the delta. Gonçalves' forces initially consisted of ten ships and 80 Portuguese. By March 1609, he had a contingent of men and 200 horses from Bakla, and possessed his own 40+ jalias, some oared navios, and 400 Portuguese. Upon taking Sandwip, he promised the people that he would not hurt them or seize their property if they brought the remaining Muslims to him. When the locals returned with some 1000 captives, they were beheaded.

Gonçalves and his band of survivors became pirates, attacking the Arakanese, robbing in Arakanese waters, and selling the booty in the ports of their ally Pratapaditya. But instead of giving Pratapaditya half of Sandwip's revenues as promised, Gonçalves seized the strategically located Dakhin Shahbazpur island which belonged to Pratapaditya.

His army now had over 1000 Portuguese, 2000 indigenous troops, and a 200-man cavalry. His navy was just as large: it had 20 oared navios with metal-plated bows armed with big falcões; 70 war jalias, not including the 250 jalias and barges used by merchants; and three big, oared galeotas, each with two 25-pound guns, each mounted with falcões. There is no doubt that marginal points on the northern Bay of Bengal could often co-opt large numbers of people into their armies.

Gonçalves' forces introduced a new volatility into Sandwip's politics. The attack on Pratapaditya changed the amicable relations between the local rulers and the Portuguese. But under Gonçalves, Sandwip became once again the key to southeast Bengal and a destabilising factor for Arakan.

According to Michael Charney, an occasion for intervention came in 1609, when Min Razagyi and Chittagong's governor or myd-za, Anaporam, clashed. Min Razagyi demanded Anaporam's white elephant, a symbol of luck and an emblem of royalty. Anaporam refused and Min Razagyi, having made the demand to test his loyalty, attacked him. Anaporam allied with Gonçalves, who demanded his women as hostages. With this agreement, Gonçalves and Anaporam faced the Arakan army, but were routed. Gonçalves and de Brito consulted together (surprisingly!) and moved Anaporam to Sandwip with his family, fortune, and elephants. He lived there as an exile until his death soon after, 'not without suspicion of poison'.

Min Razagyi now faced a new threat on his north-western border, a greater threat than de Brito posed in Syriam. He could no longer depend upon his governors for absolute loyalty, and Tripura was emerging as a hostile neighbour.

Expansion: 1611–17

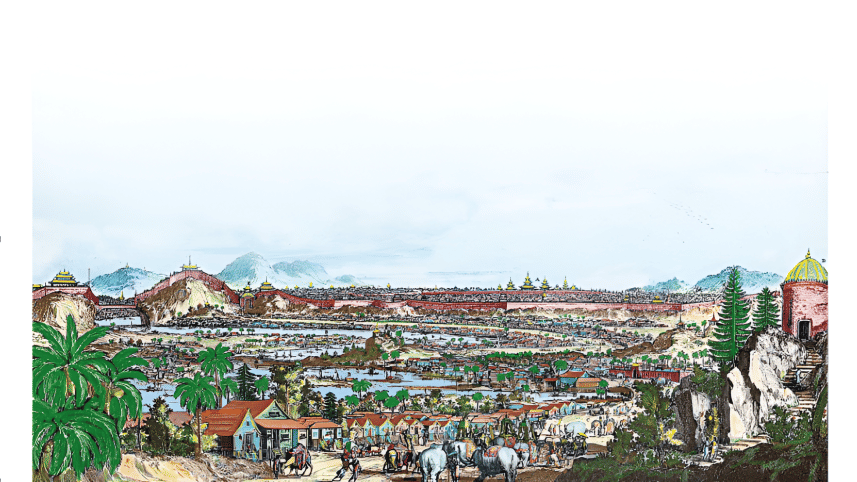

Sandwip kept challenging Arakanese royal authority. After raiding the coast (image 1) and destroying coastal fortifications, Gonçalves blocked the entire coast, including Chittagong. The renewed coastal blockade prompted Min Razagyi's younger son, Min Mangri, who had been appointed the new myd-za of Chittagong in 1609–10, to ally with Gonçalves and rebel against royal authority in 1612.

By this time, the Mughals had advanced to nearby Bhulua. In 1611, Min Razagyi and Gonçalves jointly mounted a campaign against them. But Gonçalves seized the Arakanese naval contingent, killed the commanders, and sold the crew into slavery at nearby ports; while on land, without naval support, Min Razagyi was soundly defeated.

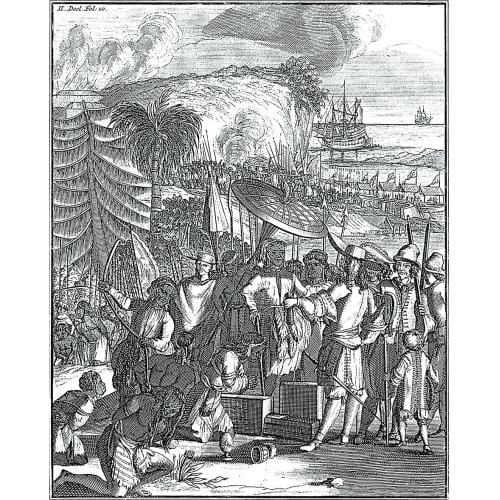

Gonçalves' forces became even bolder. In 1615 they, along with an official fleet from Goa, sailed up the Lemro River, attacked Arakanese and foreign vessels anchored there, and raided the capital, Mrauk U, but were ultimately routed by the Arakanese with Dutch help. It was perhaps the only time Gonçalves asked for Goa's help. He never co-operated with the Estado da Índia's headquarters at Goa.

The upstream capital port-city of Mrauk U was supposedly impregnable, lying on a large fluvial network with an ingenious system of canals and sluices that linked it to the sea (image 2). The Italian merchant and traveller Cesare Federici noted that it was designed with a system of sluices that could repel invasions but facilitate trade and communication. He said:

'This King of Rachim hath his seate in the middle coast betweene Bengala and Pegu, and the greatest enemy hee hath is the King of Pegu: which King of Pegu imagineth night and day, to make this King of Rachim his subject, but by no meanes he is able to doe it: because the King of Pegu, hath no power or armie by sea. And this King of Rachim may arme two hundreth Galleyes or Fusts by Sea, and by Lande he hath certaine sluses with the which when the king of Pegu pretendeth any harme towardes him, hee may at his pleasure drowne a great part of his Countrey'.

Scholar Maurice Collis wrote:

'Geographically speaking, the situation of Mrauk-U is peculiar. It lies sixty miles from the coast, but the largest ocean-going ships of that period could reach it through a network of deep creeks by which it is surrounded. This gave it the advantages of a port, without the attending risk of surprise by an enemy fleet. A large rice growing area immediately enveloped it'.

Gonçalves' blockade limited Arakan's access to maritime revenues and affected the upstream Arakan–Ava trade. Maritime commerce, and supplies of firearms and mercenaries, stopped until 1617, when Gonçalves was defeated at Sandwip. But Mrauk U was still left in command of agricultural and demographic resources with which to dominate the littoral until maritime trade resumed. Any decline in commercial resources could also be offset by a resumption of raids into neighbouring kingdoms, which provided a direct source of goods and treasures available for redistribution by the king. Later kings intensified raids on Bengal and Lower Burma for booty and captives to be used domestically or sold as slaves elsewhere.

To offset Portuguese hegemony, Arakan courted the Dutch, and in the 1620s they established a permanent factory at Mrauk U. To meet the Dutch need for labour and food to feed their slave labourers, the court developed an interconnected rice-and-slave trade for the next half-century. At least into the 1630s, Arakan effected some degree of success in bringing back Muslim traders and other Asian commerce. Fray Sebastião Manrique noted the presence in Mrauk U of traders from around the Bay, from 'Bengala, Masulipatam, Tenasserim, Martaban, Aceh, and Jakarta'.

Evaluating Gonçalves

Gonçalves escaped after the battle of 1617. According to a dispatch the Count of Redondo sent to Lisbon, he died later that year at Hugli.

As a pirate king, Gonçalves' policy was to force all ship captains in the area to submit to his control and compel all merchant shipping to come to Sandwip. In this, his scheme was very similar to that of de Brito. Gonçalves seems to have succeeded, for in one Portuguese royal document he is said to have 'subjected all the coast of Bengala [including Arakan]' and with 'these fortresses he controls the commerce from those parts'.

However, Gonçalves' notion of Portuguese expansion in the Bay was very different from that of de Brito. His plans did not include wider Portuguese control over the Bay as de Brito had envisaged. Unlike de Brito, Gonçalves never co-operated with Goa except in the case of the joint Sandwip–Goa campaign attacking Mrauk U in 1615. He always ignored the viceroy's plans and became involved in wars with mainland rulers. He usually went against de Brito, who tried to bring him under the Estado's jurisdiction. But local issues triumphed over imperial concerns when he allied with de Brito in the Anaporam matter of 1609.

The Portuguese Crown's plans for the Bay failed with Syriam's loss in 1613 and Sandwip's loss in 1617. Plans were revived between 1629–43 when Manrique dreamt of revitalising, with Arakan's help, the informal Bay empire.

A central aim of this project was to drive out the Mughals with Arakan's help; unfortunately for him, this plan never saw the light of day. The career of Sandwip highlights how, due to lacklustre policy-making in Lisbon and Goa, Portugal missed the chance to put its Bay empire on an official footing. Portuguese organisation was stripped of its political autonomy, and the commercial activities and independent overall command structure which the Portuguese had previously enjoyed were gone.

A Slave Port

After 1617, the area was calm. Chittagong became the only commercial port due to its proximity to the rich Meghna trade, but Min Khamaung ended its traditional autonomy. Its semi-independent status and proximity to Dianga's Portuguese settlement had allowed Anaporam and Min Mangri to revolt. Now ruled by a viceroy close to the royal family instead of a governor as earlier, Chittagong was brought under royal control.

Sandwip became a slave port, shipping captives down the Coromandel coast and into Goa for sale and trans-shipment into Europe. It also became a nodal point for the slave trade through Arakan into Southeast Asia. The Portuguese were no longer a factor. Only two powers remained: the Mughals and the Arakanese. Using the Portuguese who had been captured on Sandwip in 1617, and its own Arakanese slavers, Arakan raided Lower Bengal as far as Orissa for slaves and booty over the next few decades (image 3).

Min Khamaung resettled the Portuguese near Chittagong, not as traders involved in the entrepôt trade, but as servicemen to raid Lower Bengal. As royal servicemen, their role as competitors to Muslim traders was now largely reduced. They were either forced into Arakan's military or commanded to operate their jalias (galleasses, an oared war boat in Bengal and Arakan) under royal supervision. This service-group was called harmad (a corruption of 'armada'), and the 'headman' of their group was capithomor (capitãomor).

No longer free, the servicemen were placed under the supervision of Chittagong's viceroy, to whom they gave half of their booty. The Mrauk U court gave the capithos (capitães) bilatas (revenue-producing lands), from whose income they maintained their individual crews on their own lands. But they drew their income largely from their relationship with Chittagong's viceroy. The practice of forcibly keeping Portuguese women and children in Arakanese territory helped to ensure loyalty, or at least dependence on Arakan.

A 17th-Century Decline?

Should we assess Sandwip's career against the 17th-century resource crunch and commercial decay along the Bay of Bengal that the historian Anthony Reid wrote about? As resources declined, fringe areas in most kingdoms sought to break away. The flux from Portuguese expansion actually helped accelerate the process of state formation within some areas. But it remains unclear whether it was commercial vitality or decline that aided the emergence of state forms in southeast Bengal. Sripur declined in the face of Mughal onslaughts; Sandwip rose with Portuguese activity and fell when the informal empire declined.

Pratapaditya's kingdom of Chandecan, with its string of delta ports, flourished at this time. By controlling the port of Chandradwip (Bakla) after an alliance with Kandarpanarain Rai, Chandecan's eastern borders approached Sandwip. This enabled it to dabble in Sandwip's affairs. In alliance with Arakan, Pratapaditya attacked the Portuguese in 1603 (beheading Carvalho), but then supported Gonçalves against both the Mughals and Kedar Rai in 1609. Once again, local issues won out over larger concerns. This expansive kingdom ended when Pratapaditya was defeated by the Mughals.

Epilogue

Sandwip's turbulence reveals the southeast's response to imperial expansion at a time when small polities were facing legitimacy crises. Sandwip's strange history shows how lesser ports and the 'minor' Portuguese settlements could play a decisive role in the fate of empires.

Unlike the Mughals, local polities took an interest in Sandwip because it was vital to the maritime economy on which they depended—an economy in which the Mughals had little interest. In the Mughal land-based vision, Sandwip was purely a strategic asset. The Portuguese, however, appreciated Sandwip's strategic and commercial importance. But its location and physical environment were both boon and disaster.

It was a boon because it commanded the Bay, yet its politics and physical environment made it an island that was difficult to control. Sandwip's exceptional position was attractive, but its autonomy was a disaster because its location between two expanding frontiers—deltaic Bengal and coastal Arakan—made it impossible to govern.

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and the author of India in the Indian Ocean World (Springer 2022).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments