My experience as an editor of a Bangla magazine

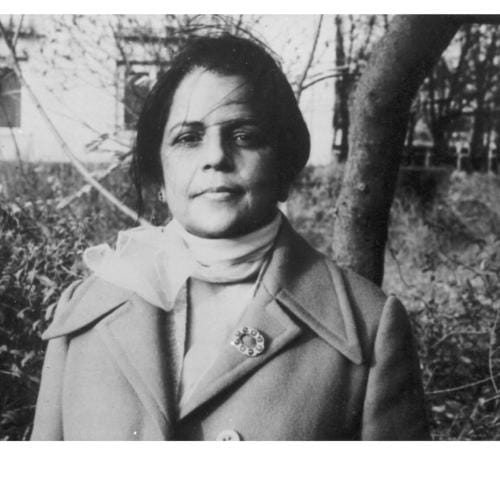

I edited a journal called Edesh-Ekal for some years and have indeed a story to tell. Before I start my story I would like to tell you who I am and what was the setting in which I conceived the idea of publishing a journal. I am Noorjehan Murshid, as you have already gathered, and I come from Murshidabad. My surname Murshid, of course, has nothing to do with Murshidabad. My name is not from Murshidabad but from an accident with which I have been living for slightly over four decades now.

I was educated at the Victoria Institution in Calcutta and the Universities of Calcutta and Boston. My first job after my graduation from Calcutta was that of Headmistress of a Girls' High School in Barisal at the ripe age of twenty two. While I was waiting for the result of my M.A. examination, I was appointed Superintendent of a Post Graduate Women Students' Hostel in Calcutta known as Mannujan Hall. At the same time, I joined All India Radio as a broadcaster.

With partition I opted for Pakistan, for me, which meant Dhaka and my destiny. I joined politics in 1954 and got elected to the East Pakistan Legislative Assembly on a United Front ticket by defeating a distinguished Muslim Leaguer and educationist, Begum Shamsunnahar Mahmud. Since 1954 I have been actively involved in politics both in and out of power. But with the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the murder of my colleagues -- Tajuddin Ahmad, Syed Nazrul Islam, Monsur Ali and Quamruzzaman -- in jail, I lost heart and sort of withdrew from politics. All over the subcontinent, there was turmoil. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was hanged, Indira Gandhi was assassinated and we were deeply depressed.

The military in power in Bangladesh formed political parties to get support from the people and gave rise to a kind of politics for which I had only repulsion. During the long night of military rule in one guise or another, which only ended recently, the country was politically debased and economically ruined. Greed, violence and unemployment created a situation of lawlessness and general insecurity which hit women specially hard.

My journal was born in these circumstances and in response to my own need for a worthwhile occupation as well as to the situation in the country. When I brought out my journal, I felt that there was a need for it. You bring out a journal at a particular time when you strongly believe that you have something special to say and that there are people in society who want it said. Most of our people are poor and without rights and exploited. Even so, women are poorer and more exploited and deprived than men. The idea of social justice was accepted and current but it did not seem to include the notion of equal rights for men and women. The journal wanted to draw attention to this long-standing default and to work for the equality of woman and man. This, we thought, would be possible only in a sane, civilised and just society, and our aim was to contribute to the creation of such a society. The concept of the journal and its range of interests were expressed through its different sections which were: "The World," "Country", "Society", "Interviews", "Literature", "Miscellaneous Reflections" "Debate", "T.V.," the "Theatre" and "Letter from Abroad".

I recall with pleasure that the first issue contained articles on the origin of the dowry system in Bangladesh, women workers in industry, women's representation in Parliament, a long extract from Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex in Bengali translation, and a discussion on the subject of women and development. The allocation of space among the various interest reflected the balance we kept in view. We wanted Edesh-Ekal to say something to all citizens and at the same time to maintain a strong focus on women and their problems. Thus, we hoped to avoid giving the impression of representing a female "ghetto." When the journal came out it was indeed very well received. The editor got dozens of congratulatory letters. It was reviewed favourably by the newspapers and periodicals. I used to send my journals to the cities, district towns and even to rural areas. But the actual readership of the journal was limited to a small section of the middle class. I was surprised to notice that I was receiving letters not only from different parts of West Bengal, but also from Bengali readers from Bombay and Delhi. I had a few readers in the U.K. and America as well.

I started the venture without any institutional support. Most of the support came from my family. I created a fund with contributions from my husband and children and my own savings. When I decided to bring out the journal, I was optimistic, indeed, too optimistic. I wanted to print 10,000 copies. After a great deal of persuasion by Obaidul Islam, the head of the Bangla Academy Press and my husband, I agreed to reduce the number to 5000 and soon realised that even that would be too large and scaled it down to 3000 copies with great reluctance and annoyance. The first issue came out in August 1986.

We approached our friends and other sympathetic people for contributions and I must say, we were pleased with the responses. From the start, I wanted to lay a strong emphasis on women and women's issues and contacted almost all women writers in the country. I received some articles, stories and poems from them, but most of my contributors were men and I feel sorry to say that some of our women writers, who of course rightly call themselves writers and not women writers, were rather cool towards the magazine. They promised and never delivered.

My target groups were educated middle class men and women, who form the back-bone of our society. Unless they are aware of the causes—personal, social, national and international—behind their backwardness and exploitation, they will not be able to overcome them.

Our women are doubly exploited, for being members of an unjust society and for being women. I know cases where husbands and wives are educated and well placed in society and the wives have not only their own income but they have fortunes inherited from their parents, and still the wives are treated like slaves and sometimes get beaten up by husbands and sons, that is by the male members of the family. What could be the reason? One view is that men are interested in the money of their wives or mothers and not in them. So, you see, education alone cannot help us to protect ourselves and our interests. Intellectually, if we cannot bring ourselves to believe that, if necessary, we should leave our husband and family to save our life and dignity, we can never be equal to men. In a male dominated society, this is the worst thing that can happen to a woman. Through my journal, I wanted to reach these types of women and men.

I brought out my journal from the Bangla Academy Press. One morning Nirmalendu Goon, the poet, came to the place, sat down at my table and appointed himself my assistant. He helped with proof reading and also contributed an interesting personal column. So, I started with one assistant and a chauffeur. For the distribution of the journal, I contacted the "Hawker's Association" and gave them 1000 copies to sell, only to find out later that most of these were destroyed by white ants and rats. When I protested, they said, no one wants to buy this type of intellectual magazine. They showed me some cheap and glamorous magazines of cinema and sex and asked me to bring out something like these; otherwise, it would not sell. So the 'Hawker's Association" proved useless for me in the matter of distribution of the journal. Nirmalendu Goon could only assist me for two hours a day in proof reading, he could not help me in any other way. So I appointed a very bright girl called Sabera and a boy named Tareq to help with the distribution of the journal, collection of articles and ads, answering and mailing letters, etc.

Soon I felt the need for an office assistant, who would maintain files, answer telephone calls and record messages, keep an account of the expenses under different heads. To bring out the magazine regularly every month was my headache. Besides, of course, I had to keep an eye on everything concerning my journal. Soon I found that my overhead expenses were becoming too much for me to bear. Within two years, the resources, with which I had started, were nearly exhausted. I was bad at collecting ads. I noticed, from a distance, how confidently Dr. Mustafa Nurul Islam, the editor of the quarterly journal Sundaram, went through the gates of different business houses and organisations and got hold of their chiefs and came back with very lucrative and regular ads. Obviously, I did not have his flair for business, but I knew, I was being discriminated against. I was a woman and an ex-minister of a former government whose members were not in great favour in the commercial district of Motijheel in Dhaka.

The first step I took was to reduce my expenses. Printing charges at the Bangla Academy Press were high. So I thought of changing the Press. I tried some wayside printers, but the atmosphere in these places was rather uncongenial unlike at the Bangla Academy Press, where one could have a place to work for hours, have tea, converse with almost everybody present and meet well known literary people. The idea of sitting on a stool for long hours with my back towards a busy road didn't appeal to me. So I bought a small composing unit and hired two compositors. As is evident, the more I tried to reduce my expenditure, the more I put myself in a situation where it increased. But in spite of all these troubles, I never thought of giving the journal up. The journal used to come out regularly but understandably, with very few ads. My daughter, Sharmeen, came forward to help me in collecting ads and she really tried. She and Sabera both worked for the journal with dedication. They never thought any work for it beneath their dignity. One day the poet Nirmalendu Goon left as suddenly as he had come and took his column with him. Tareq also disappeared, probably for reasons of health. I recruited the young poet Maruf Raihan and later Raqib in their places.

After four years, I started to feel I was failing. At this moment, a young man walked in from nowhere and claimed that he knew the secret of running a magazine and making a commercial success of it—in which respect my record so far was dismal. He said that if I gave him a chance, he would bring out the journal on a particular date every month, and that until he could do that, he would not take a penny in wages — that is, he offered to give me free service until the paper had a regular income and was published on a fixed date. An attractive offer, but I was rather skeptical, and know now that I should have obeyed my instinct. Instead, I saw him draw up an impressive chart, showing the details of his plan of operation: strategies were devised for increasing circulation, deadlines were fixed for the collection of contributions from writers and ads, an uncompromisingly firm date was set for the publication. He embarked upon an expensive campaign of addressing letters to people all over the country urging them to subscribe to the magazine. In his zeal, he distributed all the copies of its back issues, including my office copies, free. He employed hawkers to do the job. I was out of Dhaka at the time for some months. He explained to my office staff that the journal should reach every educated home where there were people to read it—a laudable idea that was defeated by its originator. When I came back from abroad, I found him still struggling with the issue whose printing process had begun five months ago and which was alleged to have got mysteriously lost in the computer. The young man in question eventually brought out an issue but he took six months to do so. On top of everything, it was so badly printed and so full of printing mistakes that, in despair and anger, I literally drove him out of my office. I had the whole issue reprinted but at that point, the journal went totally broke.

And what is the moral of the story? I must play down the hilarious denouement to the affair. The switch over to computer technology need not have doomed the journal, but I obviously should not have entrusted the publication to a stranger of completely untested ability. He merely represented an avoidable mischance. The truth is, I was weary of the effort to keep the journal afloat as a deficit proposition and of the dependence on ads. I acknowledged earlier that the intellectual support I received was not unsatisfactory. The readers, too, responded well to the journal, enabling us to maintain the circulation at a reasonable level for some time. The real reason for the failure of the journal to stay alive longer than it did, is to be ascribed to certain social and economic factors. I do not know of any serious journal in this country with the exception of Sundaram, which has sustained itself for long without either institutional support or some sort of commercially or politically motivated financial backing from some source or other. When times are hard , the lower and middle classes are not very keen on spending their scarce cash on things like Edesh-Ekal. The slump in the sale of the journal, which began with the great flood of 1988, coincided with the growing strength of religious fundamentalists, a group seeking power and control over the society, especially educational institutions, with ferocity. I however think, in retrospect, that despite all this, some of the problems I spoke of would not have existed for a person with greater business acumen than I possessed. I also think that the values for which the journal stood are not only valid but basic to our conception of the society we want to build. These values and forces inimical to them are at present engaged in a deadly conflict. What is needed is not surrender, but a reincarnation of the spirit of Edesh-Ekal as a form of intelligent and assertive group action rather than lonely individual effort.

Noorjehan Murshid (1924–2003) was a women's rights activist, politician, freedom fighter, and a member of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's cabinet.

The article was initially published in a book titled Edesh Ekal: Nari (2001), which compiled selected writings on women previously published in the magazine. The book was edited by Noorjehan Murshid. On the occasion of the 16 Days of Activism to End Gender-Based Violence, The Daily Star is republishing the article to honour Noorjehan Murshid's unique experience as a female editor running a magazine and her contribution to the fight for women's emancipation.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.