Forbidden Nazrul

Both Bengals are grappling with intense periods of unrest. While the political events unfolding in these two lands may not align directly, they share one significant commonality: distrust. We see a populace that no longer has faith in its leaders. Across various sectors of society, people are expressing intense anger towards those in power, each, in their own way, saying 'NO.' The state, however, dislikes hearing no. Much like the patriarch in a traditional family, it does not tolerate dissent. To maintain its authority, it binds the people through a combination of affection and control—sometimes soft, sometimes stern. It provides cultural entertainment, subtle threats, and basic sustenance such as rations and allowances. With these comforts, the state expects its citizens to submit, stay quiet, and endure their hardships without complaint. And often, this is the case. But occasionally, there are exceptions. In such times, we witness a faint sense of desperation in those who govern. They search for instigators—the ones who fan the flames of public anger—and they attempt to silence them.

The charm of Western verse had begun to make its mark on Bengali poetry. Yet, in this very decade, Nazrul Islam witnessed a suppression of his expression and literary efforts, as his work faced relentless attacks and effacement. Over time, at least five of his books were banned: Jugabani (1922), Bhangar Gaan (1924), Bisher Banshi (1924), Proloy Sikha (1931), and Chandrabindu (1931). Nowhere else in the subcontinent, either before independence or after, has a single poet seen so many of his works censored in such a short span. Even globally, only a few instances are comparable.

There are many ways to silence a voice. The easiest is to tempt or buy the person off. But what about the one who is unyielding, who remains uncompromising? For them, the state devises other strategies. They may be forced into exile, intimidated repeatedly, or subjected to bans on their work. This has been the way of things across nations and eras. But to what extent can oppression bend the spine of someone who dares to say "no"? Does burning books, banning writing, or censoring expression truly mark the end of an author? How does a writer carry on, day by day, with censorship looming overhead? And what mindset drives those who impose these bans? In this space, let us address these questions through the life and works of Kazi Nazrul Islam, journeying through the global history of literary censorship to understand the broader implications of suppression and voicing.

Bengali poetry heralded modernism in the 1920s, which was the very first decade of Kazi Nazrul Islam's literary life. The charm of Western verse had begun to make its mark on Bengali poetry. Yet, in this very decade, Nazrul Islam witnessed a suppression of his expression and literary efforts, as his work faced relentless attacks and effacement. Over time, at least five of his books were banned: Jugabani (1922), Bhangar Gaan (1924), Bisher Banshi (1924), Proloy Sikha (1931), and Chandrabindu (1931). Nowhere else in the subcontinent, either before independence or after, has a single poet seen so many of his works censored in such a short span. Even globally, only a few instances are comparable. Bengali poetry has been richly productive, but none of its poets had to bear such repression. Why would a state feel threatened by a poet—a creator whose sole weapon was his words? Why did the state go to such lengths to suppress and persecute him? To find the answer, we should go back in time.

The origin of literary censorship can be traced back to ancient Greece. The philosopher Socrates managed to establish an intellectual community, only to later face charges for supposedly 'corrupting' young minds through incessantly questioning the state and denying the supremacy of the gods. Among the three people who accused Socrates was a poet named Meletus. In Euthyphro (circa 5th century BC), Plato described Meletus as the youngest among the accusers and noted that Socrates was unfamiliar with him prior to the trial. When the votes were cast, 500 Athenians participated, and Socrates lost by a margin of just 60 votes, receiving 220 in his favour. The result: he was sentenced to death by drinking a poisonous potion of hemlock.

In 1616, the Church warned Galileo Galilei to cease promoting heliocentrism, the theory that the Sun is at the centre of the solar system. His Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632) led to his trial. Initially jailed, he then spent eight years under house arrest. Publicly, he was forced to renounce his beliefs. Yet five hundred years later, whose truth endures? The Church's truth, or Galileo's? Who is more respected today, Meletus or Socrates?

A similar fate befell Voltaire. His novel Candide (1759) and his philosophical treatise Letters Concerning the English Nation (1733) were banned for questioning the outdated conventions of French monarchy and society. Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille for eleven months and later exiled in isolation in England. His whole life was a battle to defend his ideas and beliefs. Ancient, medieval, and modern—each era offers us examples: the state remains unchanging in its resistance to new ideas. It demands loyalty, submission, and compliance. Those who resist, who refuse to surrender, become détenus.

We can bring ourselves directly to the timeline of Kazi Nazrul Islam and explore the era's international poets alongside him. Nazrul was deeply inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution, and his revolutionary fervour was further fuelled by his close leftist allies, such as Muzaffar Ahmed. Together, these influences instilled in his writings a call for the triumph of the proletariat, a celebration of revolution, and a cry for the emancipation of the masses. The first of his books to be banned was Jugabani, a collection of editorials previously published in Nabajug newspaper. Released on 27 October 1922 by Arya Publishing House, Jugabani quickly became a target, with police seizing 350 copies directly from the publisher. Notably, Nazrul employed a shrewd tactic here: while Arya Publishing House was responsible for the publication of Jugabani, Nazrul listed himself as the publisher. In this way, he shielded the publishing house from legal jeopardy, cleverly circumventing the law—a tactic reminiscent of Voltaire, who, to evade censorship, also released his works anonymously or through uncredited publishers.

In 1949, Jugabani saw its second edition in East Pakistan, with proceeds directed towards the poet's medical expenses. In Kolkata, multiple editions were published by Rupshree Press, under the guidance of Nani Mohan Saha and with Zohra Khanam as the publisher. Though Jugabani eventually faded from regular circulation in Kolkata, a century later all of its editorials are now accessible worldwide. Considering the lasting circulation and enduring impact of this collection, we realise how limited were the labels and restrictions imposed on Nazrul and his work. His editorials reveal a writer far beyond the accepted stereotype, showcasing his incisive opinions and his role as a vigilant social critic. Unlike typical newspaper articles that often lose relevance over time, Nazrul's writings in Jugabani are exceptional. They remain equally relevant to Bengalis across both sides of the border, provoking thought and engagement on pressing issues such as racism, global warming, Bengal's trade potential, Bengali nationalism, and anti-colonialism.

In one essay, The Trade of Bengalis, Nazrul advises his readers to enter business with confidence, free of any inferiority complex, writing: "We must forcibly break down this ugly high-and-low mentality embedded in our society and birth." In another editorial, Why Our Strength Doesn't Last, he critiques Bengali society's dependency on servitude: "…Why do we stand like cowards and take blows? At its core, it's the same reason—we are servants, we are employees. Can you show me a single nation that rose by working for others? For ten or fifteen rupees, we easily sell our manhood, our freedom, yet we refuse to engage in business, to try and stand on our own feet. This degrading servitude has reduced us to weakness and humiliation." Nazrul's question resonates in today's start-up-driven world, challenging us to reconsider its relevance in the present context.

Information on Nazrul Islam's significant works is accessible on Wikipedia, yet one more book merits special mention: Bhangar Gaan. Banned in 1924, this collection of eleven revolutionary poems remained absent from the public sphere for twenty-five years. However, the opening song of the collection, Karar Oi Louho Kopat, still serves as an anthem of defiance in both India and Bangladesh. If anyone asks me which Bengali song is the most timeless and powerful protest anthem, I would say it is Karar Oi Louho Kopat. Even freedom fighters and leaders such as Chittaranjan Das found inspiration in its verses during his imprisonment. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose wrote to Dilip Kumar Roy that he too had drawn strength from it. Since independence, the song has been recorded, featured in films such as Chittagong Armory Raid, and continues to resonate in collective memory. The relevance of Bhangar Gaan endures today, symbolising the spirit of rebellion in both Bangladesh and West Bengal. Each poem in Bhangar Gaan carries historical significance; this book could well have been a 'Red Book' for Bengalis. That it did not achieve this status reveals our own shortcomings and ultimately, our deep indifference towards Nazrul's legacy.

On 1 August 1924, Nazrul Islam's Bisher Banshi was published. Just a few months later, on 22 October, the government issued Gazette Notification No. 1027, banning the book under Section 99-K of the Criminal Code. Bisher Banshi, spanning only 33 pages, bore a known risk, which Nazrul acknowledged. At the beginning of the book, he wrote:

"For some time now, I have been advertising that I would publish certain poems and songs as a second volume of Agnibina. Instead, I have published them here in Bisher Banshi. For various reasons, I changed the name from Agnibina, Part / Volume II to Bisher Banshi and was compelled to omit a few poems and songs. As long as the law, in the form of 'Ayan Ghosh,' holds up its cane, it is wise to keep certain so-called 'rebellious' verses absent."

The ban on Bisher Banshi proved a blessing in disguise. Gopaldas Majumdar, owner of DM Library and publisher of the book, reflected in his memoir Smaran Baran: "It turned out to be fortunate. A few copies of Bisher Banshi had been kept in the binding room. The police did not discover them. In the midst of the storm, those hidden copies quickly sold out."

Similarly, Nazrul Islam's other books, such as Pralay Shikha and Chandrabindu, were both banned in 1931 just a few days after publication. By this time, Nazrul had already been imprisoned and, while in custody, had undertaken a gruelling 39-day hunger strike to demand better conditions for his fellow prisoners. This meant that over an entire decade he endured repeated prohibitions and repression, yet remained steadfast in his convictions. The state's arsenal of fear and censorship seemed feeble against the resolve of a poet dedicated to truth. German philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who was nearly a contemporary of Nazrul, argued that a state primarily enforces censorship for three reasons: to protect the foundations of its power, to suppress critical and penetrating thought, and to secure uniform compliance from its citizens. But often we see scientists, poets, and thinkers emerge as voices of dissent, as thorny obstacles in the path of authoritarian rule. They say no and resist authoritarianism with every fibre of their being. Nazrul's 39-day hunger strike against British colonial oppression is a towering symbol of this resistance. Despite the bans on his books, he refused to capitulate, articulating his stance in Rajbandir Jabanbandi (1923):

"I stand accused of sedition, and so today I am imprisoned and charged at the royal court… I am a poet, sent by the Creator to reveal hidden truths and to give shape to the abstract. Through the voice of the poet, God speaks, and my words are vessels of His truth. These words may be deemed treasonous in the eyes of royal judgment, but in the light of justice, they are neither an affront to justice nor a defiance of truth. The revelation of truth shall not be stifled."

Here was a poet unwilling to abandon truth, come what may. In his eyes, only the supreme truth held ultimate worth, and its expression was inevitable. No confinement could restrain him. Do we not witness in Nazrul's words and actions the timeless pursuit of truth seen since the days of Socrates? And does not this truth—no matter how much time's dust accumulates upon it—stand as the sole eternal reality?

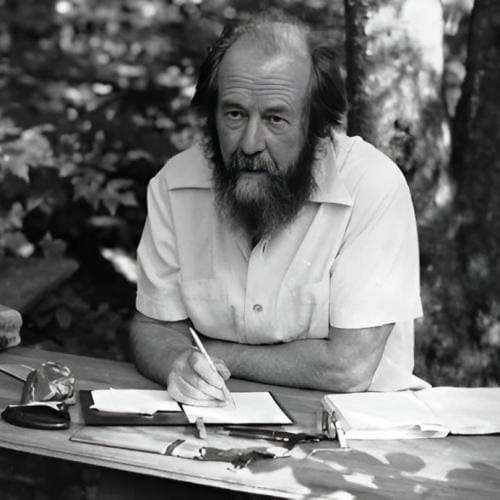

I wish to recount One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. This book laid bare the horrors of Stalin's regime, capturing the agonies of life in the gulags. The story of Ivan is, in essence, Solzhenitsyn's own testament. For eight years he endured the gulag camps as a price for not aligning with Stalin's whims. Later, after release, he was forced to live in remote Kazakhstan. When Nikita Khrushchev came to power, a debate in the Politburo arose over publishing One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, ultimately resulting in its edited publication. Khrushchev's logic was that it would expose the atrocities of Stalin's rule. But did Khrushchev truly wish for a writer's freedom, or was it purely a political manoeuvre? The irony is undeniable: this same Khrushchev had banned Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago (1957), barred him from accepting his Nobel Prize, and expelled him from the Writers' Union. Pasternak had to plead with Khrushchev, saying, "Leaving my homeland would be equal to death." Khrushchev's treatment of Solzhenitsyn and Pasternak reveals an eternal condition—beneath the mask, the face of power remains the same, and the poet's fate is sealed.

The Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, another of Nazrul's contemporaries, faced repeated bans from 1925 to 1946 under Soviet rule. She was expelled from the Writers' Union, accused of political indifference, excessive mysticism, and ultimately labelled as "decadent" by the Communist Party. Politburo member Andrey Zhdanov went as far as to publicly call her a "harlot-nun." Her Requiem, a poetic testament to the life of repression, remained unpublished in her homeland until the 1980s.

The question remains: does a poet's fate change with shifts in society? Does a change in nation or a change in leadership alter the state's restrictions? The answer, it seems, is a resounding no. For instance, in 1982, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, a leftist poet from West Bengal, was denied the Nehru Soviet Land Prize by the Communist Party of West Bengal for translating Solzhenitsyn's work. But history is not without irony. Rulers who tried to silence poets have come and gone, while the poets' verses endure. Solzhenitsyn, Nazrul Islam, Akhmatova, and Mukhopadhyay—all survive through the legacy of their words, dancing across blank pages, defying centuries. No authority has the power to sever this lifeline of truth.

Arka Deb is the Editor-in-Chief at Inscript.me and author of the book Kazi Nazrul Islam's Journalism – A Critique.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments