Early North Bengal: A (re-)creation and a lone journey

Early North Bengal (ENB) is a vast tract with natural boundaries in early times, but later divided by an international border into two unequal parts, the larger one in Bangladesh and the smaller in Indian West Bengal. The book on it focuses not on what it is today but on how its society, economy, and cultural life could have been in the period 3,000–1,400 years ago. The remnants of the past, substantial yet varied in size and composition, remained in wait for centuries to speak out to someone ready to lend them an ear. A large part of it was lost forever. A small fraction has been collected and conserved. They are fortunate to return amidst humans for whom they were once created. But even they seem to whisper something that has remained untold.

Searches for the past history of ENB began about a quarter and two hundred years ago by a British national, Francis Buchanan, entailing a process of explorations and excavations which, however, never reached the scale required for opening its past. Naturally, ENB, which was mentioned as Puṇḍravardhana-bhukti in the Gupta epigraphs, remained mostly understudied although archaeologically, in terms of sites, sculptures, and epigraphs, it was the richest part of Bengal. Many of its inscribed sources were deciphered, image sculptures were identified, and sites were enlisted. But no attempt was made to synthesise the data for an integrated history of this part, seemingly due to the notion that a homeland of Bengalis should be studied as one geographical unit. Historically and geographically, however, it remained divided for a long time, each having a distinct name. Vaṅga, phonetically very close to Bāṅgālā, was the name of a division where the Vaṅga people lived. The land of the Puṇḍras was situated to its north. The course of history of the two lands was conditioned by geography and travelled along two different routes. A separate study of Puṇḍravardhana was to underline that it was an essential requirement for understanding the history of Bengal.

The Puṇḍras are figured in a Brāhmaṇa text of the eighth–seventh century BCE. The Mahābhārata indicates that their homeland was situated to the east of the Ganga from where it took a southward turn. Epigraphic, literary, and geographic sources give a rough idea that it stretched up to the Tista–Karatoya to form its eastern boundary. The Puṇḍras, however, are not found in any occupation in individual capacity or group work in social, political, administrative, or religious platforms. The mention of their king as a political head in relation to the battle of Kurukshetra and the legendary Kṛṣṇa is more conventional and sometimes mythical. The appellation Puṇḍra seems to have been losing relevance for non-use, and a new term Varendra appeared with a restricted geographical denotation but enduring cultural connotation. Puṇḍravardhana-bhukti as a provincial unit remained alive in government documents.

The actual work of writing was laced with several problems. Early texts regarding the history of ENB were very rare and largely inspired by religion or normativity. The written records of land transfers were also issued with religious purposes. The eulogies (praśastis) are laudatory narratives of a successful few enjoying prestige and power in religious or political domains. What then remained that could be processed for historical information was the question that struck me after a few trials of writing something on this tract. It was in such a frustrating situation that the idea occurred to reach out to the scattered remains of the past to see whether some historical insights or moments related to any particular aspect could be found.

The history of ENB is largely a reflection of a journey, lone and long. It began with uncertainty, knowing not what new I would ultimately find. For explorative tours, training in archaeology is almost indispensable. Familiarity with iconography is equally essential. Being a student of Ancient Indian History and Culture, I had some ideas about the former, but iconography was foreign to me. I, therefore, threw myself into a field for which I believed I was an outsider. I was hesitant, a bit nervous too—especially about iconography—as I started writing about my new finds because of that strong feeling. One of the two examiners of my PhD thesis was an art historian. B.D. Chattopadhyaya, my supervisor, needed to be assured that the images dealt with were iconographically correct. I analysed the image sculptures more for historical information in terms of social and religio-cultural trends. But wrong iconography could have spoiled the conclusions, and the thesis would have needed to be rewritten. For the historical part extracted from images and other sources, there was a historian examiner. But discussions during the viva voce assured me that my approach to images for a purpose beyond iconography struck the right chord. It was applied convincingly and in wider context in Early North Bengal: from Puṇḍravardhana to Varendra (c. 400 BCE–1150 CE).

Naturally, ENB, which was mentioned as Puṇḍravardhana-bhukti in the Gupta epigraphs, remained mostly understudied although archaeologically, in terms of sites, sculptures, and epigraphs, it was the richest part of Bengal.

The seed was sown on the evening of the day I had faced the viva voce. Prof. Chattopadhyaya, his wife, and I were on an after-dinner stroll along the internal roads of Jawaharlal Nehru University. I asked him if I should prepare articles from the sub-topics of the thesis. His quick, short, and compelling reply was, 'It will be a book.' It was quite unexpected; during the viva voce, his expressions were very critical, and no one knew better than I that he was quite right in his judgement. The thesis needed more engaging analysis and conclusions, but I had rushed to submit it, necessitated by certain reasons. Seconds after, a slow wave of happiness spread through me. I understood: the thesis needs to be adapted for a greater audience.

Making a book, I realised, meant adding more information, both substantive and insightful. It meant more fieldwork. Over time, my ability to understand the potential of images grew. I developed a skill of communication with the motifs, humans, deities, divine figures, and other elements—all contained in a small space of a stele, yet each having a distinct place and role. Iconography is indeed rooted deeply in society. No other source of history could provide social linkages with different categories of people, or the positions and status of men and women, as effectively as the visuals on the lower space of images earmarked for the human world. All the items on a stele, from the celestial and terrestrial to the nether world, were conceptualised in human minds, and it was humans who selected the lower space for their world. The deities on them lost their identity during several centuries of hibernation in water bodies or beneath the surface. Now they need knowledgeable persons in iconography to regain that identity.

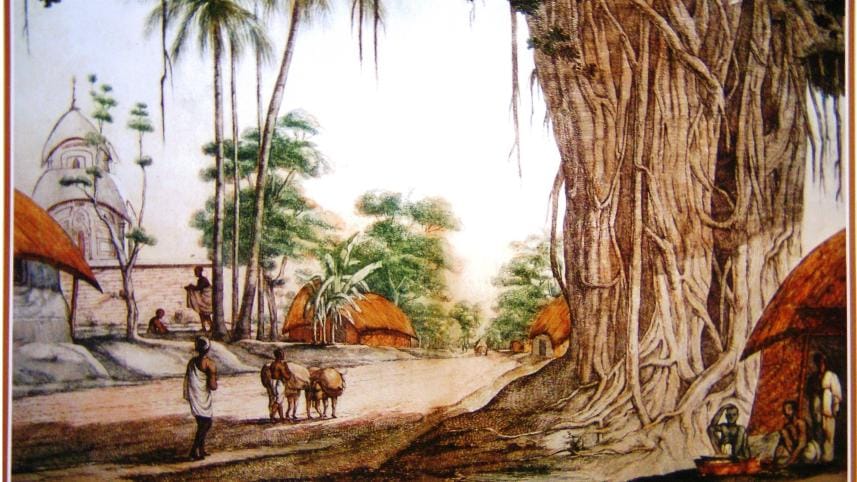

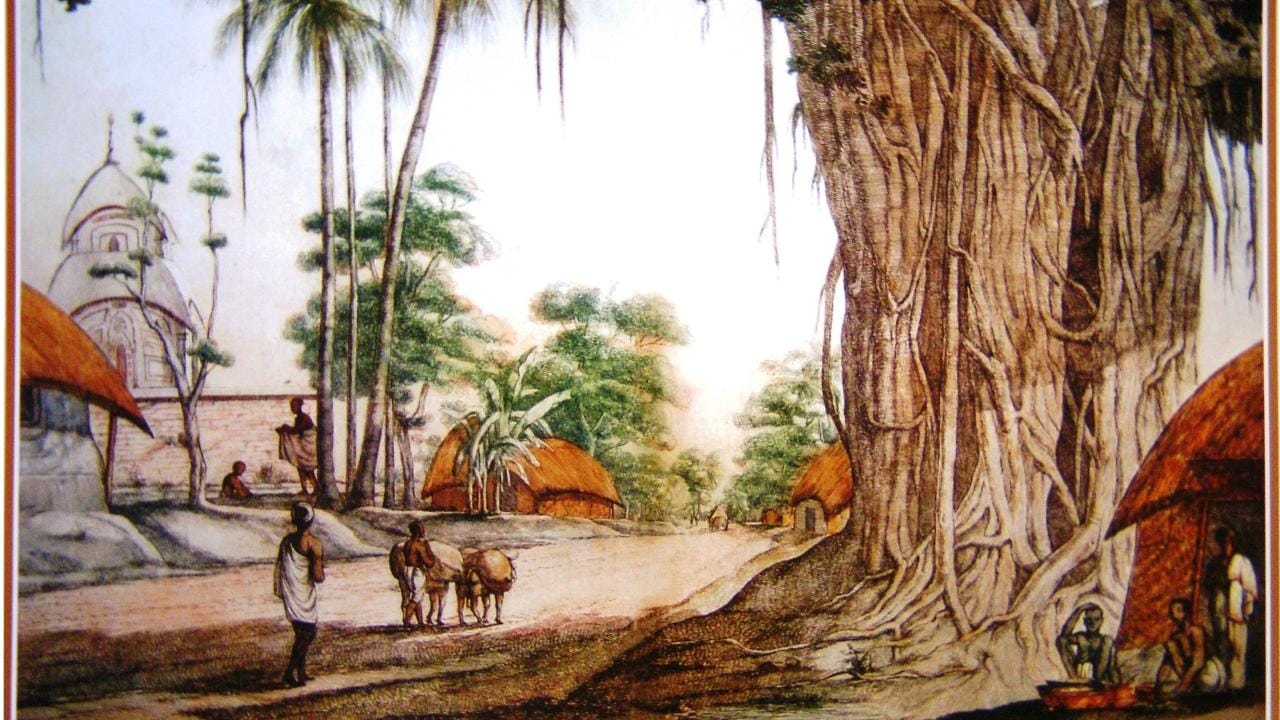

The more I travelled, the more I became involved with the past which, however, remained extensively present in rural Bengal: on house walls (old bricks), in home-shrines (deities on steles, pillars, or door-jambs), in open sacred places called thān or Gambhirātalā (old stones, images, and other items), in the scatters of architectural parts or blocks used for making images (washing stones, thrashing stones, paving stones), and in mounds with remnants of structures. But the past appeared too extensive and unmanageable for a lone explorer. Even a selective approach required teamwork over many years. Selectiveness, however, is necessary; history does not need everything that survives across time. When a number of traits characterising Puṇḍravardhana seemed identifiable, I stopped. New archaeological discoveries would continue, requiring new researchers to handle them.

Structurally, the book has two basic dimensions: surface geography and cultural geography. All other affairs and traits stemmed from them. Key findings from fieldwork that enriched our knowledge derived from large inscriptions may now be highlighted. Revealing the multidimensional identity, potential, and geographic extension of the Bangarh locality had been long overdue. The city of Bangarh had an abiding presence in cultural India, requiring a large urban area in the immediate neighbourhood of the city. The discovery of several networks of creeks in the Tapan block—which otherwise does not have a river flowing through its prosperous cluster of settlement sites on the southern stretch of the city—is very important for understanding the rich background of the city. The creeks seem to have helped more effectively than a single channel could have done. They ran by important sites located during fieldwork, facilitated internal connectivity, irrigated agricultural plots, and seem to have acted as a supply line to the river Punarbhava at some distance from Bangarh city. A large number of sites from pre-Pāla times, and a few even from pre-Gupta times, together with the creeks and the channel of the Punarbhava, created a dependable hinterland in the adjacent stretch of Bangarh city.

Re-examination of the large inscriptions indicated that the Brāhmaṇas, already a very strong class, had been living in somewhat shared status relationships with another influential class who were placed as heads in hierarchical administrative units, trade, banking, accounting, and record keeping—securing the top social position similar, or even superior, to that reserved for the Brāhmaṇas. But the bhaṭṭas, śarmās, miśras, and svāmīs finally solidified their rank distinction decisively in Pāla times, ending a long practice of representing land donors—the dattas, dāsas, mitras, pālas, nandīs, etc.—with a clear Brāhmaṇa rank. Also, the same source shows that the learned and wealthiest section of the Brāhmaṇas consciously maintained distance from the not-so-learned Brāhmaṇa community.

Sculptures, in two distinct components—image and icon—and dedicatory inscriptions were the potential first-hand sources without which several aspects of our socio-cultural life remained unknown. A religious practice impacted social psychology in a profound way. Images were donated to obtain relief from distressful situations and also to earn merit. Installation of an image in a temple had other social implications beneficial to the dedicator. Places of worship were platforms for gathering on special days of worship or for other occasions as well. The dedicator of an image received instant popularity and prestige for his act of munificence. Image dedication also aided the process of integration of tribal groups from the periphery into the Brāhmaṇical social system.

A small group of donors wished to remain in public memory for as long as his/her name on the sculpture of hard material would survive. Local priests who managed the process of installation were also benefited materially. A considerable group chose to have their names known conjointly with the name of the god represented in the image. Personal adoration was made public, while the association of the god's name with the devotee's gave assurance of protection and worked as an identity marker for both. Another group found the term dānapati as a suitable introductory designation, perhaps ignoring its restrictive original use by a Buddhist. Yet another group needed nothing to introduce themselves but installed an image in a temple, engraving their own names in dialect. They were the first-time dedicators from non-refined sections. The society had remained a dynamic structure, not an inert organ.

Female donors reveal a society unknown from literary sources. They dedicated images as individuals, not as dependent members of a family. They had the freedom to step out into open places and had their personal names inscribed, sometimes with the same honorific śrī as some male donors did. Some of them specified the varṇa rank, adding bhaṭṭinī or the introductory dānapatnī with their personal names. Each bhaṭṭinī did not need to disclose whether she was a wife or a daughter of a bhaṭṭa Brāhmaṇa. A queen used rājñī as a title in the same way as one rājaputra did. She too avoided a standard introduction. These examples reveal unequivocally that a lady was known by her personal name in society.

A meticulous exercise of comparison in line with chronological phase and numerical strength in major settled units revealed that the Buddhist monastics failed to make ENB a Buddhist stronghold. Quite contrary to popular belief, Buddhism never stood as a challenging force to Brāhmaṇism. Icons of ENB are another source showing that a class of Śaivācāryas of the Saiddhāntik school enjoyed immense influence in royalty and religious-cultural spaces until the end of early medieval ENB.

A close examination of sculptures in stone and metal shows that literary sources alone cannot offer a dependable history of early Bengal or, for that matter, early India.

Ranjusri Ghosh is an independent researchers and author of the book Early North Bengal: from Puṇḍravardhana to Varendra c. 400 BCE-1150 CE.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments