Dhaka’s Forgotten WWII Story: Spielberg’s Father and the Bridge Busters

When we think of World War II, Dhaka rarely enters the conversation. Our minds turn to images of the beaches of Normandy, the ruins of Stalingrad, and Europe. Yet in 1944, Dhaka, then part of British India, played a pivotal role in the Allied campaign against Japan. Dhaka became a base for supply lines, troop movements, and a squadron of American pilots who would earn the nickname the "Burma Bridge Busters." Among them was a young radio operator named Arnold Spielberg, father of the future filmmaker Steven Spielberg.

Most of Dhaka's war story has slipped into obscurity. Overshadowed by the grand narratives of Normandy, Stalingrad, and Pearl Harbor, the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theatre is branded as the "Forgotten Theatre." But for those who served here, the memories were vivid: bamboo barracks, monsoon skies, and the endless struggle to destroy bridges deep in Burma.

490TH BOMBARDMENT SQUADRON

The story begins on 8 September 1942, when the US Army split the "11th Bombardment Squadron" to create a new unit: the "490th Bombardment Squadron." With only 45 men and a single B-25 bomber plane given to the squadron two months later, the unit was modest in size at first. Over time, they grew in size and strength, flying the B-25C and B-26D bomber planes.

The squadron's first mission was on 18 February 1943. Six B-25 bomber planes were sent to bomb a rail station near Shanghai. But from Kurmitola, the target would shift to bridges in Burma, the supply route and lifeline of the Japanese Army.

It was in May 1943 that the 490th BS (Bombardment Squadron) was moved from Ondal, an Allied military post or air base in India, to Dhaka, 200 miles east, at Kurmitola—very near the Burma battlefield. The move to Kurmitola happened because the British soldiers were losing heavily against the Japanese army and the Allies needed to be closer to the front. Moving from Ondal to Kurmitola proved very challenging because of rail line difficulties. They had to break up their luggage several times, and it took more than a week to move completely.

Nayeem Hoq, in his book Dhaka during World War 2, wrote about Ivo Rodrick Greenwell and Arnold Spielberg, both members of the 490th Bombardment Squadron who were stationed at Kurmitola, Dhaka, at the end of World War II.

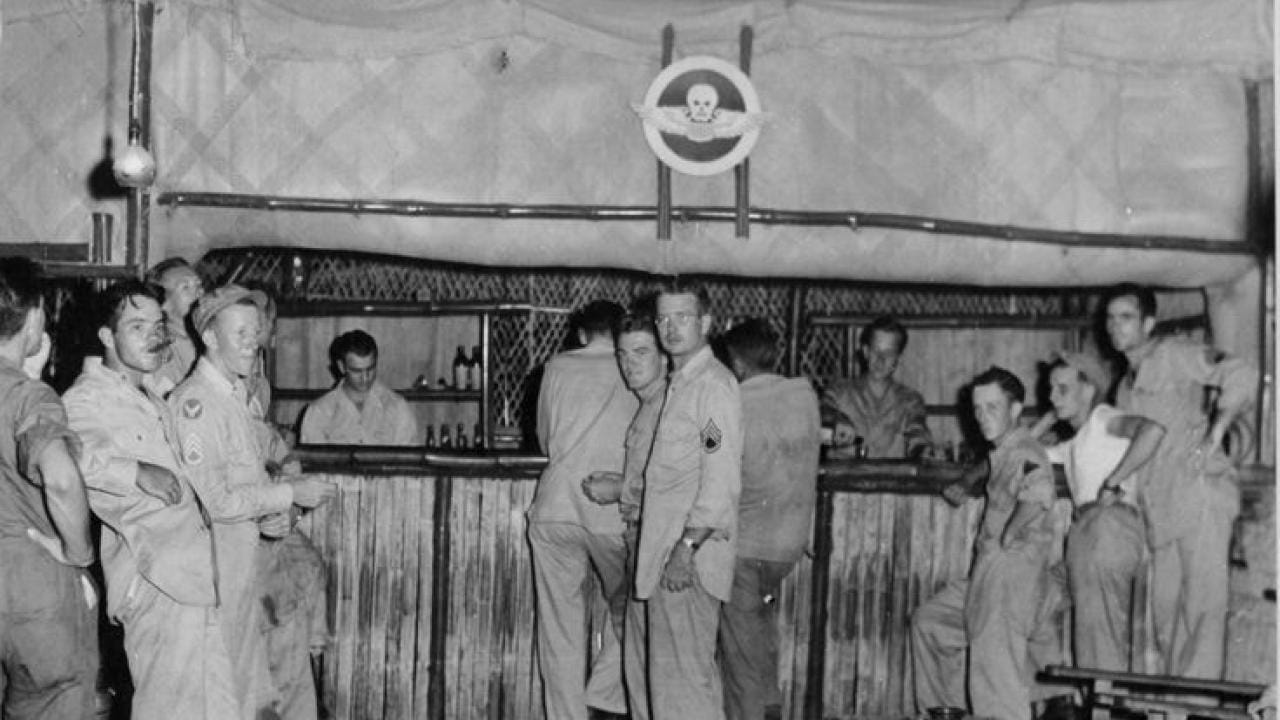

LIFE AT KURMITOLA

When Ivo Greenwell came to Kurmitola, it was still under construction. He told Nayeem Hoq: "The camp was relatively big and most of the construction was incomplete." They had to work on the walls of storage rooms. One part of the military building was used as office space. Soldiers had places inside Kurmitola quarters to live. They slept in bamboo-walled, straw-roofed houses. Locals were hired to maintain these quarters. A 15-year-old boy named Bini was assigned to look after Ivo's quarter.

The rainy season was like an omen for camp operations. Sometimes even bombardment had to stop because of heavy rain. The sight of knee-deep water was not pretty for the transportation crew. Mosquitoes and bats were another problem in Kurmitola. They had mosquito nets against the insects, but bats would rip the nets to shreds while the quarters were empty.

Ivo Greenwell was part of a group of 21 men from the ordnance group trained to load bombs safely onto B-25 planes. He remembered the precision required because one mistake in handling could be fatal.

Ivo's journey to Kurmitola was long and arduous. Ground infantries were first stationed at "Malir Airstrip" north of Karachi. After arriving in Karachi via Santa Paula, he and other GIs (ground infantry) trained at various bases—first at a strip north of Karachi, then at Allahabad where Ivo was promoted to Corporal, and finally at Ondal. Ivo and 300 other ground infantries trained at the Meriland School as part of the "1106 Ordnance Group." Two weeks after coming to Ondal, Ivo selected 20 soldiers of his liking and joined the 490th BS (Bombardment Squadron).

Although both Ivo and Arnold came to Karachi via the same ship, Santa Paula, they never met on board because the decks were divided in accordance with rank.

ARNOLD SPIELBERG: THE RADIO MAN

While Ivo Greenwell represented the bombardment crew, Arnold Spielberg represented the technical heart of the squadron. Arnold, at only nine years old, had created a radio for his personal use. At 15, he became an amateur "ham" radio operator. He also became very proficient with Morse code, able to send and receive 25 words a minute. After the Pearl Harbor attack in 1942, Arnold enlisted in the US Army and realised that his experience as a ham radio operator would come in handy.

Arnold Spielberg was a radio operator and chief communications man for the 490th Bombardment Squadron during World War II. His job was to keep the radios alive—repairing systems, designing antennas for the B-25s, and training gunners in Morse code. In the brutal weather of Bengal, when voice transmissions often failed, code was the only lifeline between bombers and base.

Spielberg later described the squadron's reputation with pride in conversation with Norm Dewitt in 2017: "We had some crazy pilots who did some crazy things—some made it, and some lost their lives, but we had a wonderful squadron."

THE STRUGGLE TO DESTROY BRIDGES

The 490th BS's primary objective was to bombard rail lines, army camps, and supply depots in Burma to disrupt Japanese supply lines and transportation. The squadron's goal during their operations in Burma was to incapacitate Japanese forces by destroying crucial bridges that served as vital transportation routes.

The reality was frustrating and disappointing. Bridges were narrow, often just twenty feet across, and the bombsight was nearly useless from 10,000 feet. Pilots risked everything, diving through gorges to line up a shot, sometimes smashing into cliffs on the pull-up.

Failures piled up. Bombs rolled off target, plunging into rivers before exploding. Pilots and other soldiers in the bombardment squadron became hopeless, and morale was low. Among them, "bridges" became synonymous with "failure."

Carpet or saturation bombing, where vast amounts of bombs were dropped at the same time to destroy the target, was used effectively in Europe but was not an option here. Supplies were limited, and the terrain demanded smaller planes. For a time, it seemed the squadron's mission was doomed.

Then came a breakthrough. By accident, a pilot named Captain Erdin, when flying over a tree line, nosed down steeply and released his bomb, which slammed directly into a bridge. The technique, later called "hop-bombing," transformed the squadron's effectiveness. They began practising it, perfecting low-altitude strikes that drove bombs into the structures instead of skipping past them.

From Kurmitola, missions reached as far as the Mu River Bridge in Burma, 370 miles away. Between February 1943 and August 1945, the 490th BS flew 615 missions, dropped more than 8 million pounds of bombs, and destroyed 192 bridges. The nickname "Burma Bridge Busters" was rightfully earned by the members of the 490th BS.

TECHNOLOGY AND SURVIVAL

Spielberg's role extended beyond radios. He helped implement a Bendix radio compass in the planes, a device that allowed pilots to home in on transmitters and find their way back to base through the storms.

The compass, however, carried risk. The transmitter could act as a beacon for enemy aircraft. Spielberg recalled that the beacon was never on all the time, but they often kept it on anyway as they had good fighter protection. The squadron endured "yellow alerts" but never a direct attack. In the end, Dhaka's airfields were spared Japanese bombing raids.

Not every mission ended well. Some B-25s went down under Japanese fire, their crews never seen again. The men knew the limits of their planes. If a bomber failed to return within five and a half hours, hope quickly faded and everybody assumed the worst.

Fortunate pilots and aircrew would sometimes bail out before the crash, but that meant another kind of terror—falling into Japanese hands. In the book Dhaka during World War 2, Ivo Greenwell recalled occasions when bailed-out members made it back to Kurmitola. It took around two to three weeks of struggle to find the path back to Kurmitola from enemy territory.

MAD BEER BOMBER OF KURMITOLA

War was not all missions and mechanics. In fair weather, soldiers of the 490th squad found escape through baseball. Eight teams formed a league at Kurmitola, with tournaments that brought some resemblance of home. The prize for the winning team was ten cases of beer.

Unsurprisingly, beer was scarce at that time in Dhaka. Once, the 490th BS received a message from the 10th Air Force Headquarters that a US shipment had just arrived in Kolkata harbour. Two B-25s were dispatched quickly from Dhaka to fetch beers from the shipment. Special wooden racks were built to hold the cargo. The whole camp was impatiently waiting for the beers. On the return flight, eager to announce their arrival, a pilot tipped his plane upward before landing. The manoeuvre flung open the storage door, and cases of beer tumbled from the sky like rain. The theatricality of the situation left the waiting ground infantries perplexed, but they quickly recovered, turning the accident into an impromptu competition. The officer in charge forbade them from opening the cases, but the GIs (ground infantry) ignored him. The pilot responsible for this failed stunt was given the name "Mad Beer Bomber of Kurmitola" by the rest of the squadron.

Dhaka's role in the story of World War II is little known. Yet for men like Ivo Greenwell and Arnold Spielberg, it was where they risked their lives, built camaraderie, and left a mark on the war. The squadron's tally speaks for itself: 615 missions, 192 bridges destroyed—a contribution that crippled Japanese supply lines and helped shift momentum in Asia.

Today, that Kurmitola has vanished under the city's expansion. Few reminders remain of the huts or runways where the Burma Bridge Busters lived. But the stories endure—in memoirs, in interviews, and in the unlikely connection between wartime Dhaka and the man who would one day raise a son to reimagine war on the silver screen.

Ystiaque Ahmed is a journalist at The Daily Star. He can be reached at ystiaque1998@gmail.com.

Follow The Daily Star Slow Reads on Facebook for more long-form stories crafted for thoughtful readers. To contribute your article to The Daily Star Slow Reads, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments