Badruddin Umar: A tribute

Teacher, comrade, and lifelong revolutionary Badruddin Umar (20 December 1931 – 7 September 2025) is no more. We offer him our deepest respect and love. Alongside this, on behalf of the people of Bangladesh, we convey our gratitude — for he devoted his entire life, thought, and activism to the cause of the people.

Born in 1931 in Bardhaman, his father Abul Hashim was a prominent organiser of the anti-British movement in the region, a campaigner for a united Bengal, and a recognised leader of the progressive wing of the Muslim League. In 1950, amid the poisonous fumes of communalism, the family moved to Dhaka. Umar became actively involved in the Language Movement of 1952 and later emerged as a pioneering researcher of that movement. After completing his studies at Dhaka University, he went on to Oxford, where he earned degrees in politics, philosophy, and economics. Upon his return, he began teaching at Dhaka University and later played a key role in establishing the Departments of Political Science and Sociology at Rajshahi University.

Rejecting defeat, surrender, and the chains of servitude is the very precondition for advancing the struggle. At the end of his life, Umar could justly say, with deep satisfaction and immense pride, that he had worked tirelessly, all his life, with this very force.

He was one of the foremost figures in Bangladesh's education and research, and without doubt the leading theoretician of revolutionary politics in the country. In the 1960s, Umar's writings on communalism showed the way for what he termed the "return of the Bengali Muslim to their homeland." At a time when the Bengali Muslim middle class needed intellectual clarity and self-realisation to define its role against Pakistan's ruling class, his work had a profound impact. From the late 1960s, he began his monumental research on the Language Movement. Without any institutional support, he completed The Language Movement and Contemporary Politics of East Bengal, a three-volume work. His method of linking social, economic, and political contexts was remarkable. Over the decades, he went on to publish more than a hundred books in both Bengali and English.

His revolutionary stance as a theoretician was inseparable from his political practice. While writing on communalism in the 1960s, Umar came under the wrath of the Ayub–Monem regime, forcing him to leave the university and devote himself fully to politics. He left academia to free himself from the state's surveillance and to work independently. Thereafter, he both investigated society, state, and history, and dedicated himself to shaping a revolutionary political path towards a new future.

In 1974, Umar launched the monthly journal Sanskriti. After only a few issues, the journal was banned in December of that year during the state of emergency, when all newspapers and periodicals were shut down. It was revived in 1981, and Umar continued to edit and write for it until the end.

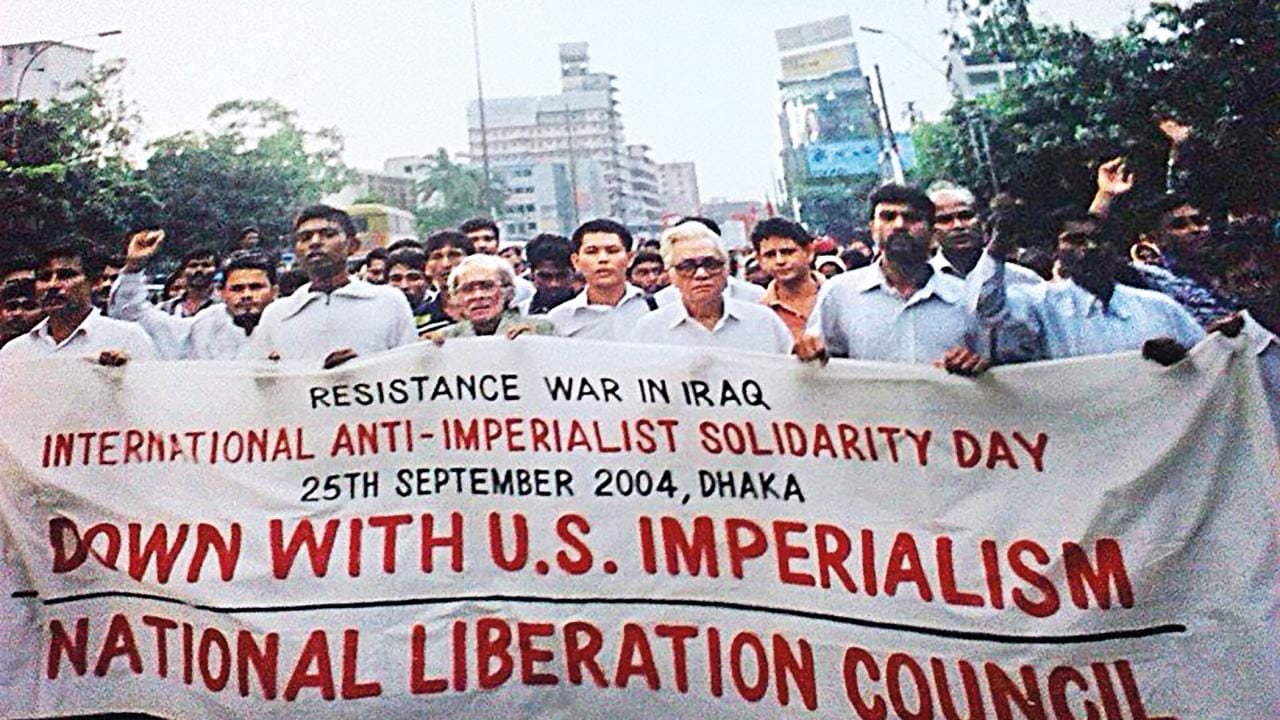

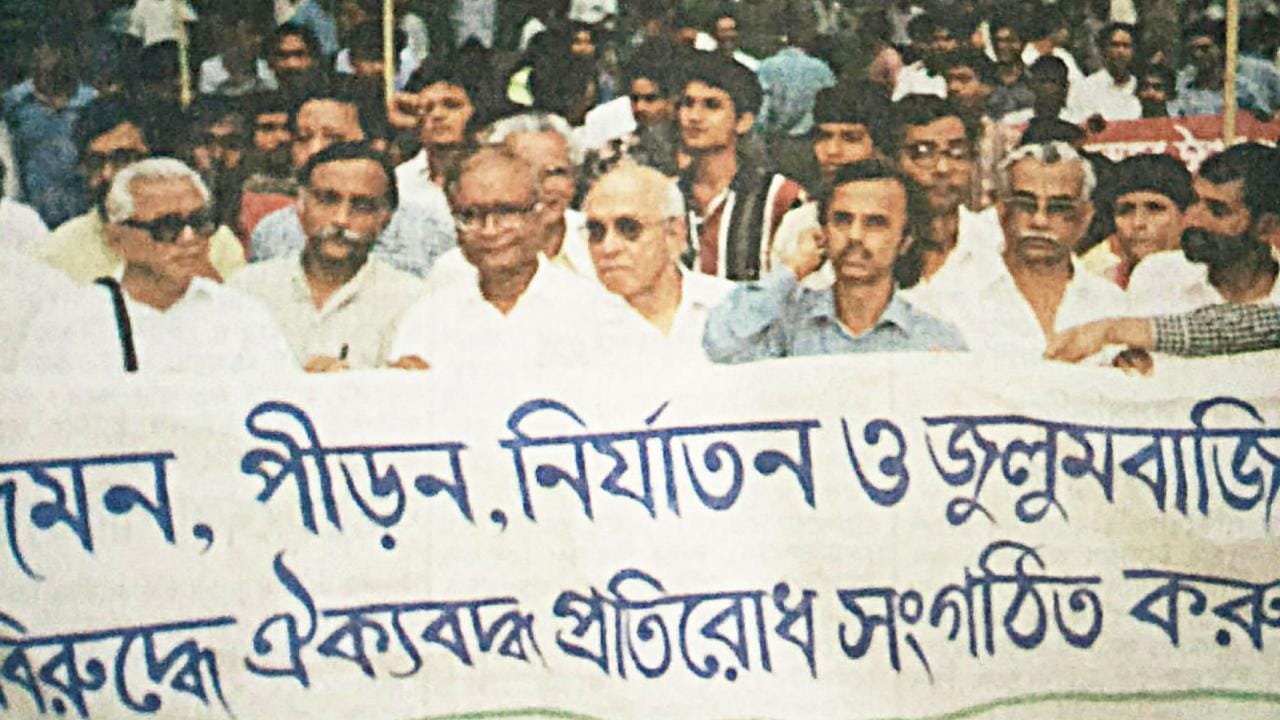

Everyone knows the sharpness and fury of his writing. Bangladesh, a peripheral country in the global capitalist order, has long been ruled by plundering and predatory forces under different names and guises. Across the world, under the banner of democracy and peace, imperialist brutality has left deep scars. In such a world, no sensitive, reflective, or responsible person can remain untouched by anger.

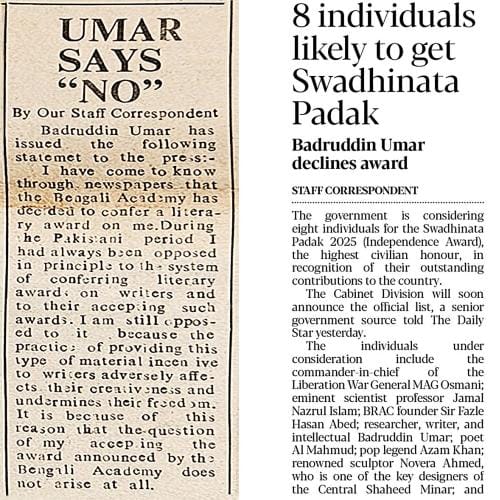

In our society, intellectual pursuit has largely been subordinated to commerce and power. Opportunism, sycophancy, and intellectual bankruptcy dominate the world of thought and politics. From outside this circle, Umar relentlessly struck at this immovable edifice. His sharp writings against exploitation, oppression, inequality, and imperialist domination consistently challenged ruling ideas. For him, intellectual labour and the politics of human emancipation were never separated. Honesty, commitment, uncompromising integrity, and firmness — all these words fit seamlessly into his life and work. Neither position, prize, nor comfort could ever tempt him away from his chosen path.

Yes, there has been a great failure in building and expanding revolutionary movements and organisations in this country; otherwise, Bangladesh would look different today. If there had been no such failures, the 180 million people of this country would have discovered themselves as free human beings, and we might have witnessed an extraordinary life in harmony between people and nature. But that failure was collective; the responsibility is shared.

Where Umar succeeded was in never surrendering, never halting. He became a symbol of profound self-respect, responsibility, and uncompromising resolve. For him, the people's current struggle for freedom is, in his own words, the "unfinished liberation struggle of 1971." Rejecting defeat, surrender, and the chains of servitude is the very precondition for advancing this struggle. At the end of his life, Umar could justly say, with deep satisfaction and immense pride, that he had worked tirelessly, all his life, with this very force.

In the exploration of Bangladesh's history, in the search for intellectual strength, and in the politics of human emancipation, Badruddin Umar will forever remain inseparable.

Anu Muhammad is a former professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments