Abul Hashim’s Bangalistaan

The decade leading up to the Partition of India in 1947 was marked by a heightened need for political self-representation among the Indian population. Various formulations of what this identity should be were offered by the dominant political parties in British India. The All India Muslim League (AIML), founded in Dhaka in 1906, became the political representative body for Muslim interests, pitted against the Hindu majority in the country. Its provincial bodies, however, often struggled to accept some of the views and strategies adopted by the AIML at the centre. They were unsure how best to mobilise and strengthen Muslim sentiments and mould them into a well-defined political identity.

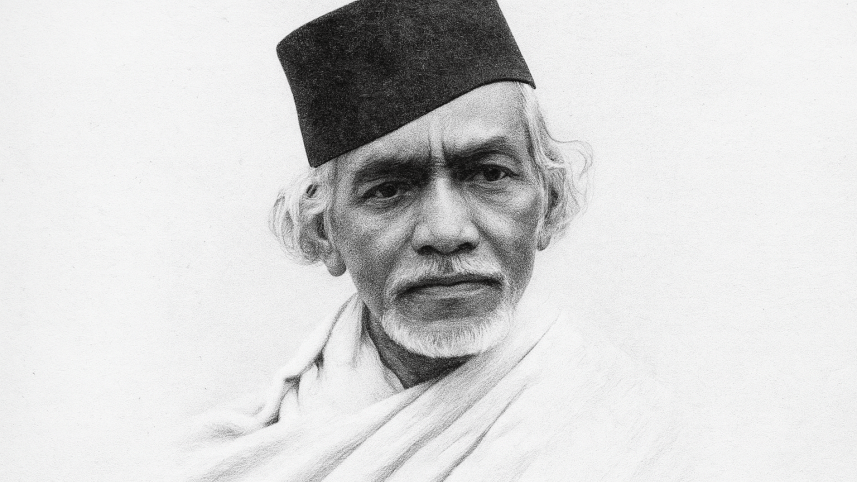

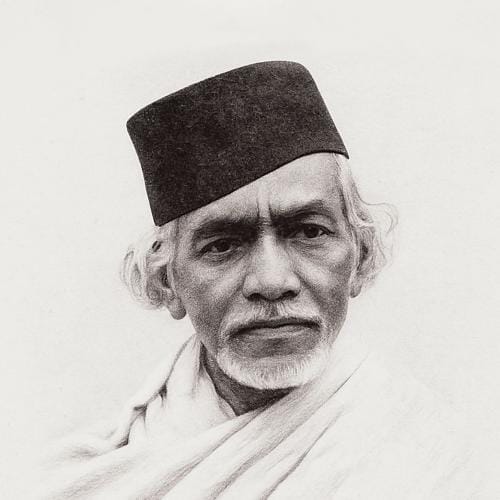

For the Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML), the question of a Bengali Muslim political identity could not side-step the proper acknowledgement of the group's social and linguistic uniqueness from Muslims in other parts of British India. At a time when communal tensions were rising between Hindus and Muslims—caused mainly by religious polarisation and a struggle for power at the centre—the chance for cohesion and peace between the two communities at the provincial level was becoming increasingly impossible to achieve. A prominent leader of the BPML, Abul Hashim (1905–74), offered his own philosophical views, some of which were later incorporated into political action by the party in the 1940s. He sought to create political and cultural frameworks that would make religious coexistence smooth and sustainable in the province.

Hashim was born into a prominent political family of Burdwan (now a district in West Bengal, India), where he grew up before moving to Calcutta to pursue a degree in law. His father's participation in the Bengal Congress and close ties with some of the party's founding members, such as Surendranath Banerjee, greatly influenced Hashim's political views. His political career began in 1936, when he participated in the Bengal Legislative Council, which was the upper house of the legislature in the Bengal province. Hashim's views were shaped by the political milieu of Bengal after A. K. Fazlul Huq became the province's Premier, serving from 1937 to 1943. Huq's emphasis on resolving class-related problems and prioritising the plight of the working and agrarian classes did much to influence the political atmosphere in the province.

By the early 1940s, however, the mood in the province began to change. At the historic Lahore Resolution, held in March 1940 and organised by the AIML, Hashim witnessed one of the most important political moments in Muslim politics in British India. The resolution was passed in favour of a political demand for the independence of all Muslim-majority provinces in British India.

This was a major turning point in regional Muslim politics, as it opened up the possibility of interpreting the Lahore Resolution in ways that could suit and apply to regional demands and grievances. After becoming General Secretary of the BPML in 1943, Hashim began to develop his own views on what a nation is, and on the future of Hindus and Muslims in the Bengal province. In his autobiographical book In Retrospection (1974), Hashim offers his reflections on what being a Bengali meant to him. For him, provincial identity—in his case, Bengali—preceded any other extra-regional identity. This primary identity provided the foundation for meaning-making through language, the construction of reciprocal trust among group members, and ways of using cultural commonalities to override differences of all kinds.

The basis of all language forms, regardless of their cultural location, is reconciliatory in nature, as they exhibit an inward-looking or self-reflective characteristic that allows us to place ourselves in the world. In multi-ethnic societies, the question of cultivating language forms—languages through which narrative commonalities are constituted—becomes crucial. At an individual level, language becomes the tool for self-recognition, occurring naturally within us and initiating the process by which we constitute ourselves as a 'self' in the world.

This task is accomplished through our attempt to connect our past with our present in various ways within language. The act of judiciously selecting parts of our past and connecting them to our present, in order to construct a meaningful personal narrative, is itself an act of language. This process is achieved through self-reconciliation, or self-forgiveness. Surely, this can be extended to the way we make meaning as a political collective—making reconciliation with others possible. Thus, the social schema for constructing a common narrative of who we are as a people, and the process of self-identification for a collective, is an extension of this implicit phenomenon of self-recognition.

The possibility of achieving a kind of self-reconciliation through language implies that, socially too, we are capable of attaining a form of collective reconciliation.

Hashim, in his plan for the United Bengal Movement—or what he termed Bangalistaan—believed that ethnically driven societies with a common language would benefit from using religion as a tool for political self-representation rather than relegating it to the private realm.

This universal feature of language, and its inherent ability to act as a tool of social cohesion, was recognised by Hashim. For him, institutional, political, and religious structures could be put into place and reformed in such a way that they would allow a political community to steer itself towards performing moral and ethical obligations towards one another without relying entirely on systems of punishment and coercive force. In other words, Hashim felt that a common language could serve as the basis for forming social trust amongst Hindus and Muslims.

Unlike the West—particularly Europe—where the transition from religious to civic nation-states, and the restriction of religion to the private realm, accompanied by an emphasis on the idea of civic citizenship, have been fundamental steps in the formation of political communities, Bengal's trajectory was distinct. In many ways, this Western experience has been understood as the birth of modernity, where such distinctions were viewed as the only way to create civic, secular channels of political coexistence between different communities, bound by a common nation, its laws, duties, and the set of rights to be enjoyed by its citizens.

Hashim, in his plan for the United Bengal Movement—or what he termed Bangalistaan—believed that ethnically driven societies with a common language would benefit from using religion as a tool for political self-representation rather than relegating it to the private realm. Religion, as an important institution, could, through the reform of its practices and the social frameworks emerging from it, pave the way for systems of collective reconciliation. A common language between the two religious communities in Bengal, he believed, would override communal antagonism.

In 1942, Hashim met the religious philosopher and thinker Maulana Azad Subhani, who introduced him to the concept of Rabbaniyat or Rabbanism. It deals with the fundamental philosophical question of what it means to be human and places this question within a religious framework. For Hashim, Rabbaniyat could potentially become an important tool to reform the way Islam was being practised by expanding its scope to incorporate not only the spiritual development of a person but also their cultural and social development. Rabbaniyat could thus serve as a useful instrument in shaping the way individuals interact with one another within a political collective. Rab, the divine attribute from which Rabbaniyat is derived, represents the divine Creator, Sustainer, and Evolver of the universe.

Exploring religious-linguistic frameworks as tools for building social trust was at the very heart of the United Bengal Plan. The plan itself may have failed, but it rested on strong philosophical foundations that explored various aspects of intersubjective relations in multi-ethnic societies. It emphasised the greater moral obligation to reconcile and forgive others as a means of positioning ourselves within the body politic.

Perhaps Hashim's message—demanding closer personal introspection, the need to reconcile with others, and the pursuit of individual liberation through religion—serves as an important lesson for contemporary times. The task of realising the true egalitarian ethos of democracy is not easy, but there is no denying that a serious commitment to achieving it is invaluable to the survival of heterogeneous nation-states in the years to come.

Sucharita Sen is Associate Professor of Politics at the Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JSLH), O. P. Jindal Global University (O. P. JGU), Haryana, India. Her recent book, Theorizing a Bengali Nation: Abul Hashim and the United Bengal Movement, 1937–1947, was published by Routledge, UK, in June 2024.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments