Who is really funding student elections?

Party finance in Bangladesh, while being a central question in policy formulation, has always remained in the dark. Political parties raise and spend large sums with little transparency, weak enforcement of disclosure rules, and minimal accountability. That culture has seeped into student politics, where future leaders learn the craft. Student organisations oscillate between unregulated financing and abrupt shutdowns when they become inconvenient. When elections do occur, the rules are so inconsistent that they breed cynicism rather than trust.

Looking into the rulebooks of student union elections, which have taken place or are about to, there are laws but very little implementation of them. At Dhaka University, DUCSU electoral authorities ban all financial transactions, including crowdfunding, yet provide no legitimate framework for financing a campaign. The result is predictable: funding goes underground and opaque sources gain leverage.

Jahangirnagar University takes the opposite route with explicit spending caps—Tk 4,000 for hall candidates and Tk 7,000 for central candidates—but sidesteps the core question of where the money may come from.

Rajshahi University's RUCSU and Chittagong University's CUCSU echo DUCSU's blanket prohibitions without designing workable alternatives. As demand for elected student unions grows across campuses, the absence of a clear, uniform policy produces a system that bans without guidance, caps without disclosure, and leaves enforcement to chance.

The consequences are structural, not cosmetic. After the July uprsing, student politics should have been rebuilt on ideas and mobilisation. Instead, under vague financing rules, campaigns reward those who can buy visibility and convenience.

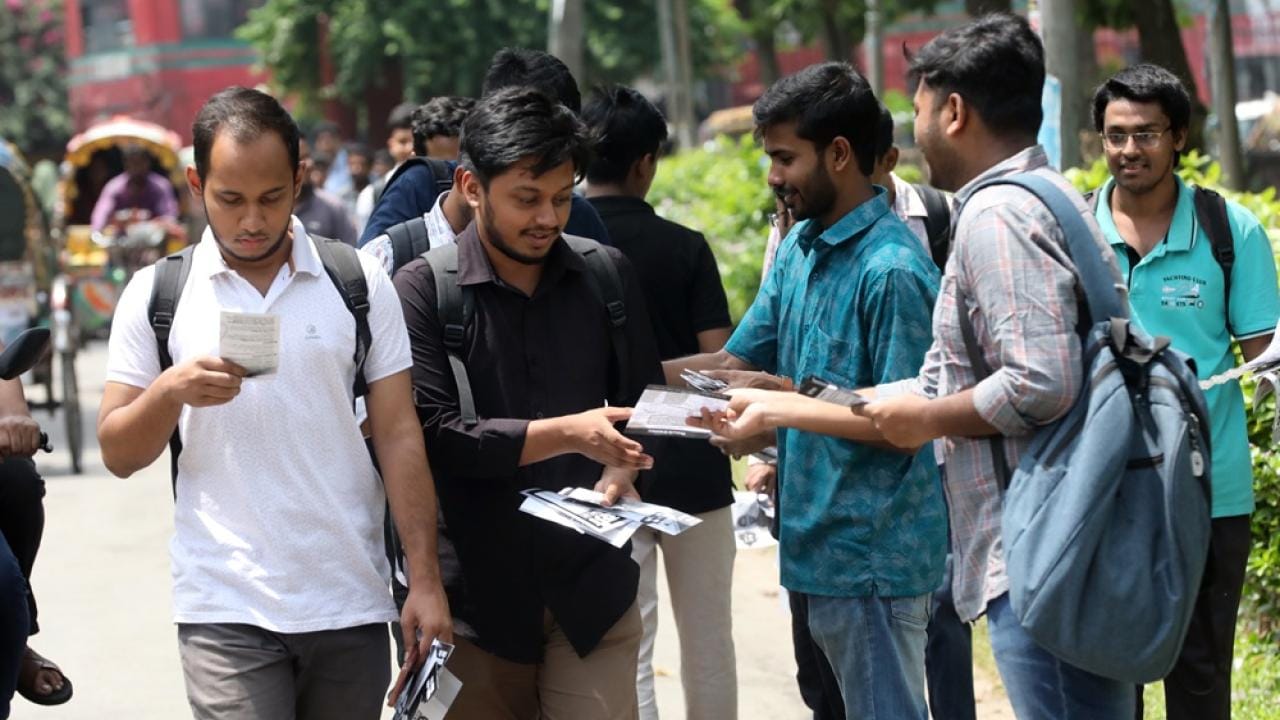

Social mobilisation theory is blunt on this point: participation is not only shaped by individuals' political ideology but also by the networks or groups they are embedded in. Building and activating large networks requires organisation, logistics, and steady money. Relentless online promotion has become a new tool of campaigning, and Facebook ads and digital boosting are central to it, yet entirely unregulated. This creates an imbalance between candidates with strong political backgrounds and individual candidates with no backing.

The impact of unregulated campaign financing is twofold. First, students at their formative stage of political grooming are exposed to a culture of unchecked rules and practices. Second, and perhaps most critically, unregulated money opens the door to external interference. This pattern is reinforced by research on party finance regulation by D. L. Wiltse, R. J. La Raja, and D. E. Apollonio.

As demand for elected student unions grows across campuses, the absence of a clear, uniform policy produces a system that bans without guidance, caps without disclosure, and leaves enforcement to chance.

In India, the Lyngdoh Committee Report of 2006, upheld by the Supreme Court, imposed tight rules to keep student elections fair and affordable. It capped spending at a modest level, banned expensive tools such as posters, vehicles, and loudspeakers, and barred linkages with national parties. The intent was simple: keep costs low so that ideas, not money, drive competition.

In the United Kingdom, the Education Act of 1994 makes student unions legally accountable for finances. Universities must ensure neutral allocation of resources that come largely from student fees, enforce expenditure limits, require audited accounts, and prevent external interference.

In the United States and much of Europe, non-profit and campus codes demand transparency, disclosure of contributions, and penalties for violations. Online activity is brought under the same principles as offline spending. Evasion still occurs, but the rules create incentives for compliance and a baseline of fairness.

Across these systems, four principles converge. First, spending caps to prevent excess. Second, bans or strict regulation of outside money to protect independence. Third, transparent disclosure of all funds. Fourth, enforceable penalties for violations. Bangladesh lags behind on each of these. In place of a coherent framework, campuses oscillate between outright prohibition and neglect, token spending caps and silence on funding sources, nominal committees and negligible enforcement. The parallel with national practice is unmistakable.

If Bangladesh wants student unions to be credible after the 2024 uprising, finance cannot be an afterthought. The opportunity is clear: student politics has been revived after years of dormancy, and this revival can be the seedbed of a democratic culture if the money problem is confronted head-on.

A workable blueprint is within reach. It should start with harmonised rules across DUCSU, JUCSU, RUCSU, CUCSU, and other unions to ensure a consistent playing field. Set spending caps that reflect local realities and allow basic campaigning without excess. Require full transparency of sources: campaigns should rely on personal contributions and small student donations, with clear bans on outside political or corporate money. Make disclosure mandatory and practical. Every candidate should maintain a simple logbook of all income and expenditures, including digital spending on ads and boosting, and file it within a specified timeframe. Subject those accounts to independent audits overseen by empowered, adequately resourced election commissions that publish summary reports. Extend the rules to the online sphere, since visibility now hinges on digital platforms.

Rules without consequences are theatre. Overspending, accepting prohibited funds, or failing to disclose accounts should trigger meaningful penalties, including disqualification or suspension. Repeat offenders should face longer bans. Universities must align disciplinary codes with election regulations so that violations carry swift and predictable outcomes.

Honesty requires acknowledging what regulation cannot do. Patronage networks will not vanish overnight. Intimidation and sporadic violence will not disappear with new forms and ledgers. But finance rules can reset the baseline. They can give independent candidates a fighting chance, reduce the incentive for external capture, and shift campaign energy from spectacle to persuasion. They can teach the next generation that democracy is a discipline of rules, not a marketplace for influence.

Bangladesh's students have long been the conscience of the nation, from the language martyrs of 1952 to the uprising of 2024. Today they face a choice. Student unions can renew campus democracy by making fair competition a lived experience, or they can slide back into cycles of money and muscle. The difference will be decided by whether finance regulation is treated as core democratic infrastructure or as a bureaucratic nuisance to be ignored.

Ignore it, and the loudest and richest will keep drowning out the most deserving voices. Enforce it, and student politics can again become a training ground for leaders who value accountability and the primacy of ideas. The stakes are not technical. They concern whether the country's future leaders learn that power is purchased or persuaded. Finance regulation is the foundation. Build it properly, and the rest of the house has a chance to stand.

Ragib Anjum and Ahmudul Haque are researchers at the Public Policy Cluster of Dacca Institute of Research and Analytics – daira.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments