Thoughts on press freedom and about a Dhaka weekly that died without a bang

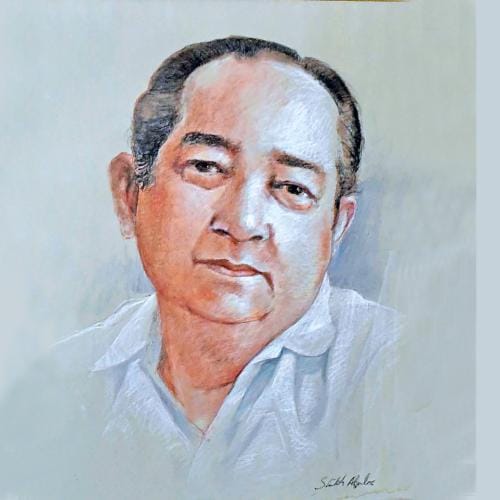

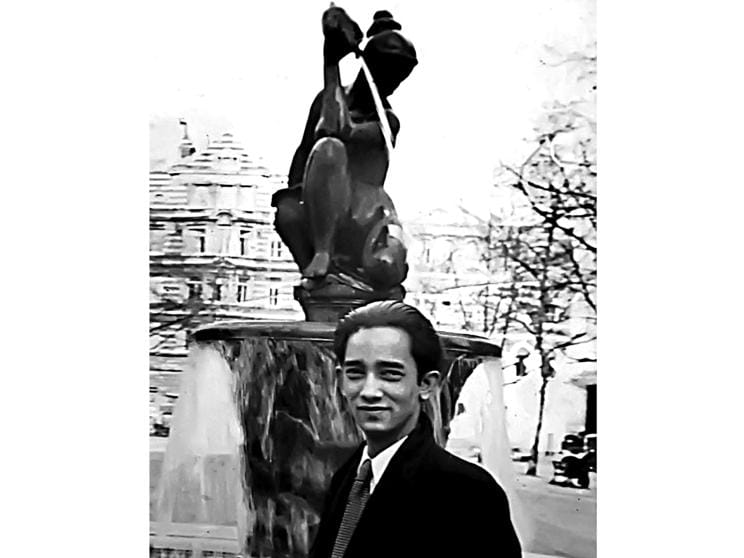

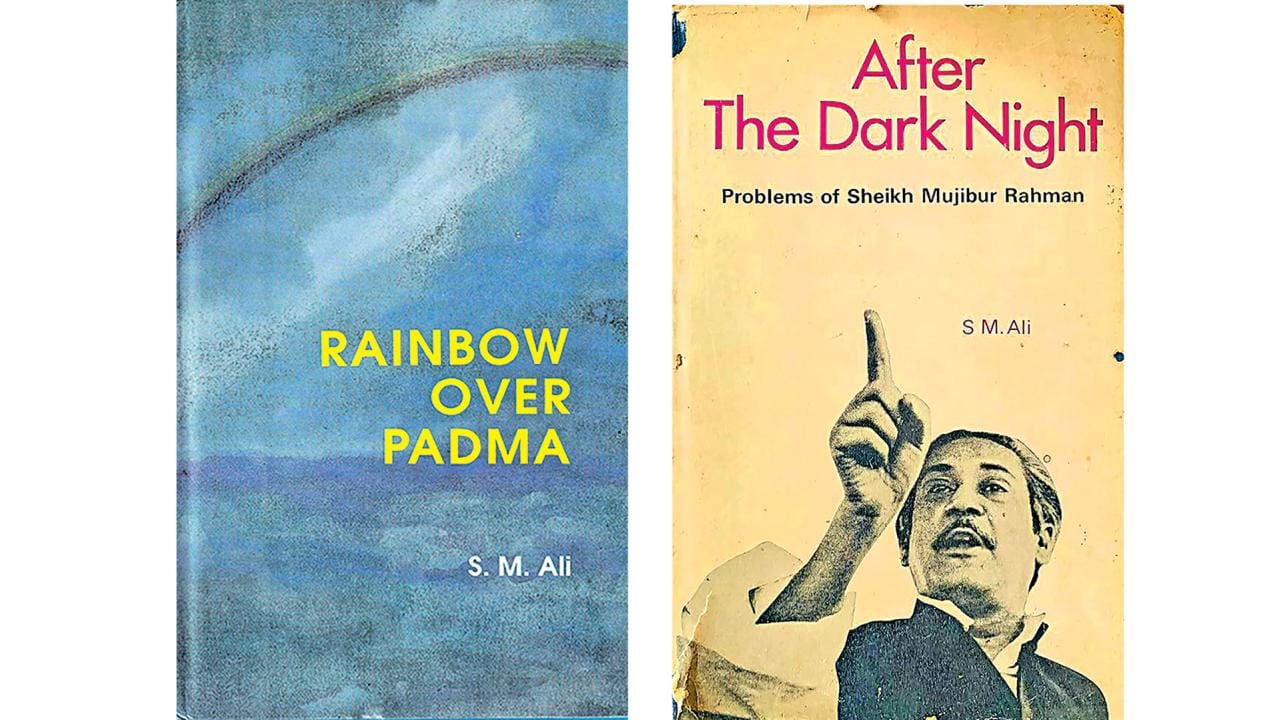

On the occasion of the 97th birth anniversary of S M Ali, a distinguished journalist and the founding editor of The Daily Star, we are reprinting one of his articles, originally published in this newspaper on June 28, 1991.

My memory gets a jolt whenever someone brings up the subject of press freedom in this or in any other country, the latest case being the observance of the Black Day, commemorating the closure of all but four newspapers in Dhaka by the then government of Bangladesh in 1974.

It surprises me that our governments, first in the then East Pakistan and then in Bangladesh, so quickly lost their patience with the press, curbed its freedom and often succeeded in turning it into a docile institution. What is particularly sad is that so often this systematic exercise was carried out by national leaders who, when they were out in the cold, had gained most from support of the media. Why was it so? And, what's more important, how can we be sure that the pattern will not be repeated in the future?

Here, my interest lies in seeing an authoritative research study on the history of our struggle for press freedom, from 1947 to 1990, undertaken by an organisation like the Press Institute of Bangladesh (PIB), perhaps in collaboration with the Bangladesh Federal Union of Journalists (BFUJ). A well-documented work would, I believe, contain such materials as the "offending" reports, articles and editorials which brought troubles for publications concerned, copies of executive orders, unless they were just verbal instructions, closing down newspapers, as in 1974, and testimonies of journalists who, in one way or another paid a price for standing up for press freedom.

The study would fill in many gaps in our knowledge of the history of the media in this country, especially in the field of press freedom.

For instance, which publication in the then East Pakistan earned the dubious distinction of being the first victim of the government's assault on the press?

When the question was raised during an informal discussion with some journalists at the PIB a few months ago, the answer seemed unanimous. It must have been the then Pakistan Observer which, thanks to its courageous editorial on corruption among associates of the then Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin got closed down, probably in 1952, and remained shut for several months. But no one was quite sure of the dates.

I suggested that the answer might be wrong. I named the East Bengal Times, a little know English-language weekly which, owned by an aristocratic Dhaka family that I remember only as the Guhas, used to come out from an old style palatial house in Wari. The building served as both the residence to the owners and the office of the weekly. The printing press, with rows and rows of wooden case of hand-set types and a treadle machine, placed in a tin shed, was also in the same compound. It was quite a compact operation.

At the time of independence in August, 1947, the East Bengal Times was a fairly well-established weekly in a city which was yet to have its first daily newspaper. Despite some difficulties that the owners had in adjusting to the changed political realities in the country — the head of the family had already migrated to Calcutta, leaving behind his son and daughter-in-law to look after the properties and the publication — the East Bengal Times carried on, along an uncertain course, without being fully aware of the distrust it caused in the mind of the Muslim League-dominated provincial administration.

Sadly enough, the weekly was on borrowed time. It seldom published critical pieces on the administration that, in matter of months, had virtually lost all its credibility with the people. However, an exception was a commentary the paper published on corruption — the subject that kept cropping up for media during the past 42 years — and immediately invited the wrath of the government of Khwaja Nazimuddin. The office of the publication was raided and ransacked. The man who paid a price was an exceptionally docile Hindu school teacher who had a part-time job in the publication. Since he admitted being the writer of the so-called offending article and took the full responsibility for its publication without any authorisation of the editor and knowledge of the other member of the staff, the police had a relatively straightforward job in hand. They took the teacher into custody and closed down the publication — for good.

The two lucky ones who were spared by the police were the Editor Ms. Kalyani Guha, the daughter-in-law of the family, and a young assistant editor — well, that's me.

I happened to be out of Dhaka, spending a vacation at Maulvi Bazar, during the police raid on the East Bengal Times. The school teacher cum journalist — I do not think, he cared to work for another publication again — had been released by the police when I returned to Dhaka after a couple of weeks. But the Guhas had left for Calcutta. Within a year or so, when we had the Observer, the Morning News and the Azad dominating the media scene of Dhaka, the East Bengal Times was nothing more than a faint memory for most of its former readers. After all, it had a small — we jokingly called it a select — circulation, an unimpressive advertising support and hardly an impact on the political scene of the province. It died without a bang, not even with a whimper.

Among the publications I have worked for, the East Bengal Times still occupies a special place in my recollections.

After all, it was this publication that gave me my first job as a journalist. It hired me, without any introduction, just by glancing through a set of clippings of a dozen or so of my articles which had been published by a Sylhet weekly. Incidentally, it was the same clippings which had earned me a seat in the Salimullah Muslim Hall and a place in the 'honours' class of English Language and Literature, despite my poor performance in the Intermediate Science examination. Like Dr Syed Moazzem Hossain, the then Provost of the Salimullah Hall and Prof. A.G Stock, the Head of the English Department, Kalayani Guha had simply looked at the faded pages which carried my byline, without really reading any of my masterpieces, the whole exercise being only a formality for hiring me.

Since the Guhas had apparently never hired a young man who was still in his teens as a journalist and were blissfully unaware of my potential, they decided to be on the safe side, from their perspective, when it came to the question of my salary. It was so low that Ms Guha could not utter the figure. She wrote it on a piece of paper, showed it to me and blushed. Then, it was my turn to blush, in a mixture of embarrassment and delight. With both of us blushing, it was a touching moment. Then, Kalayani Guha who was one of the exceedingly good-looking women I had seen in Dhaka in those days, stopped blushing and said in a reassuring voice, "it is really a pocket allowance." Instead of asking what her idea of a pocket allowance was, I nodded my immediate acceptance of the offer. As far as I knew, there was no other English-language weekly in Dhaka in those days where I could try for a job.

Whether Guhas suffered from a case of bad conscience over my salary or because they were basically decent people, they treated me very well indeed, almost like a member of the family. There were occasional free meals, endless cups of tea and snacks and an acceptance of the fact that I was the man in charge of the publication, which was really the case until the school teacher came along to share my work on the writing side and eventually to get the paper closed down.

It was a blessing that Kalyani Guha who had no journalistic experience and hardly any writing ability, remained in the background, thus leaving me alone with my work. Once in a while, she would send me a Charles Lamb type of essay, written in a sentimental vein, together with a little note asking for its publication. I would put it in, with reasonable promptness, on an inside page, but giving it just a bit of extra prominence than such a piece deserved.

For an aspiring journalist like myself, there could not have been a better training ground than the East Bengal Times. Every week, the 12-page tabloid weekly was very much my handiwork. I wrote the major pieces and provided the headlines. I edited the articles from contributors and managed to get photographs to illustrate their pieces. I did the proof-reading and laid out the pages which were printed, two pages at time, every Friday night.

After all these years, I find it a little difficult to believe that I was given such total freedom in editing the publication. I could carry out any number of journalistic experiments, including some bad ones, and introduce all kinds of imaginary bylines of non-existent writers for pieces that I wrote myself. I got most of my ideas from Calcutta publication and some from books on newspaper editing and layouts which I borrowed from the British Information Services. Thus, we got such ideas as "The Week in Review," based on news items we picked up from the Calcutta press, a "Capital Diary," a page on the international scene and another on the university. Quite a bit that went into the publication every week was surprisingly professional, but there was much which was extremely amateurish.

This strange mix hardly bothered the Guhas or the few contributors I had lined up among my friends in the university. All these writers were my seniors and, in a matter of years and decades in some cases, they made their mark on the national scene. They included A.K. Naziruddin Ahmed who served the Bangladesh Bank as its Governor in the mid-seventies; Syed Najmuddin Hashim, a former Minister for Information and an ambassador and now one of the editors of the Dialogue, and Shaheed Shahidullah Kaiser who was killed by the Razakars during the liberation war.

The East Bengal Times was just not simply a training ground for an aspiring journalist but it had also won a place for itself among budding intellectuals in Dhaka University.

So, when (and if) we have a comprehensive history of the media of this country, with special reference to the struggle for press freedom, this little known weekly that came out from Wari should provide more than a footnote; it should be a full chapter.

There will also be other chapters about publications which no longer exist and about fighters for press freedom who have also disappeared from the scene. We will talk about a few of them in this column one of these days.

SM Ali was the founding Editor of The Daily Star

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.