The future of Bengal Delta

The making of a delta

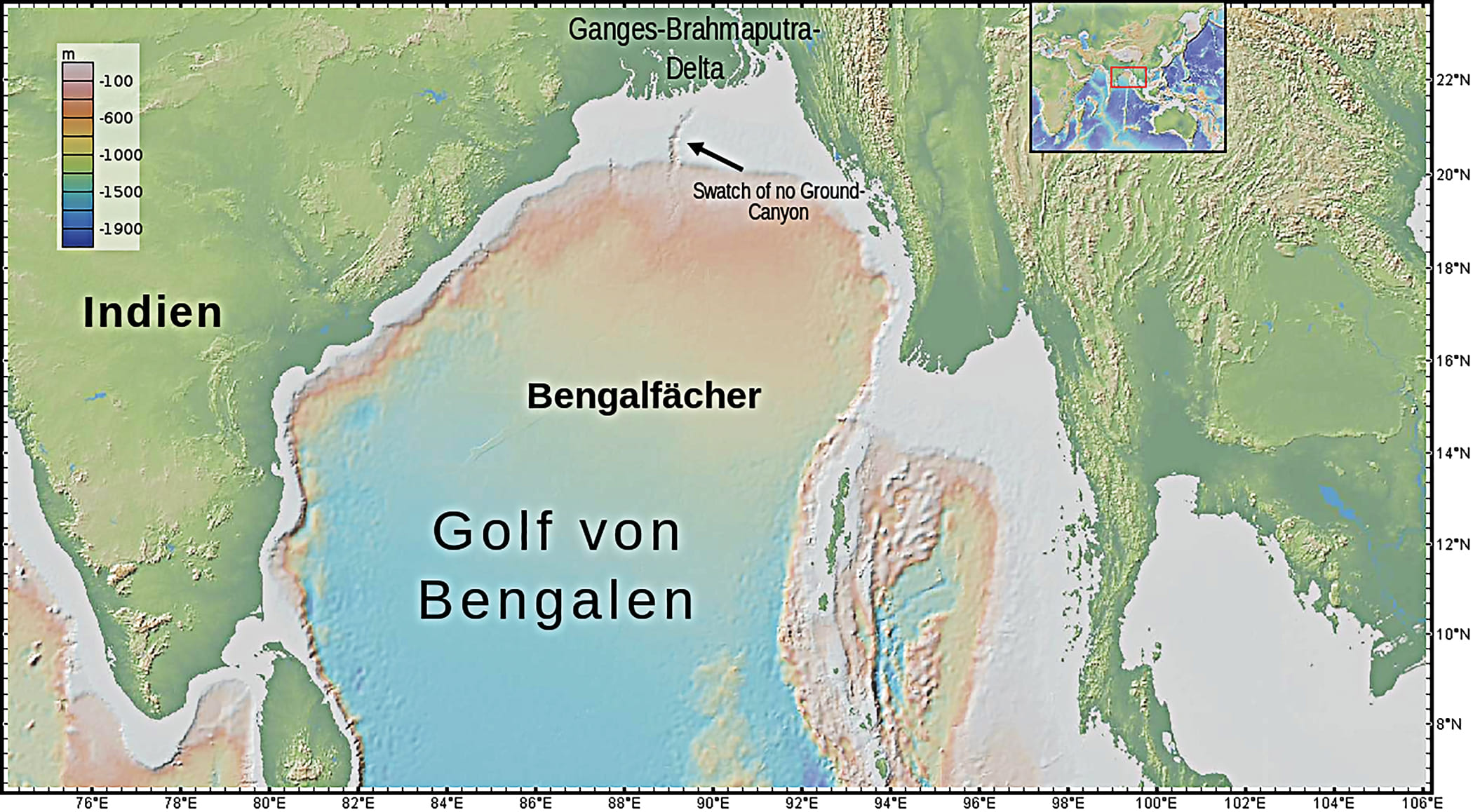

During the peak of the monsoon season, it takes the high Himalayan water only days to reach the Bay of Bengal; however, it is a different story for the sediment coming from those high places. It is the material from which the Bengal Delta has been built; some of the sediment will never reach the sea, and some will not only reach the sea but make its way down past the equator. The latter, almost 15% of the total sediment load, has helped to create the largest submarine fan in the world, the Bengal Fan, which stretches almost 3,000 kilometres south of the Bangladesh coastline. The ancient origin of the Fan, which can be traced to the Miocene Epoch more than 20 million years ago, also signals the initiation of the Bengal Delta on which the Padma River lies today.

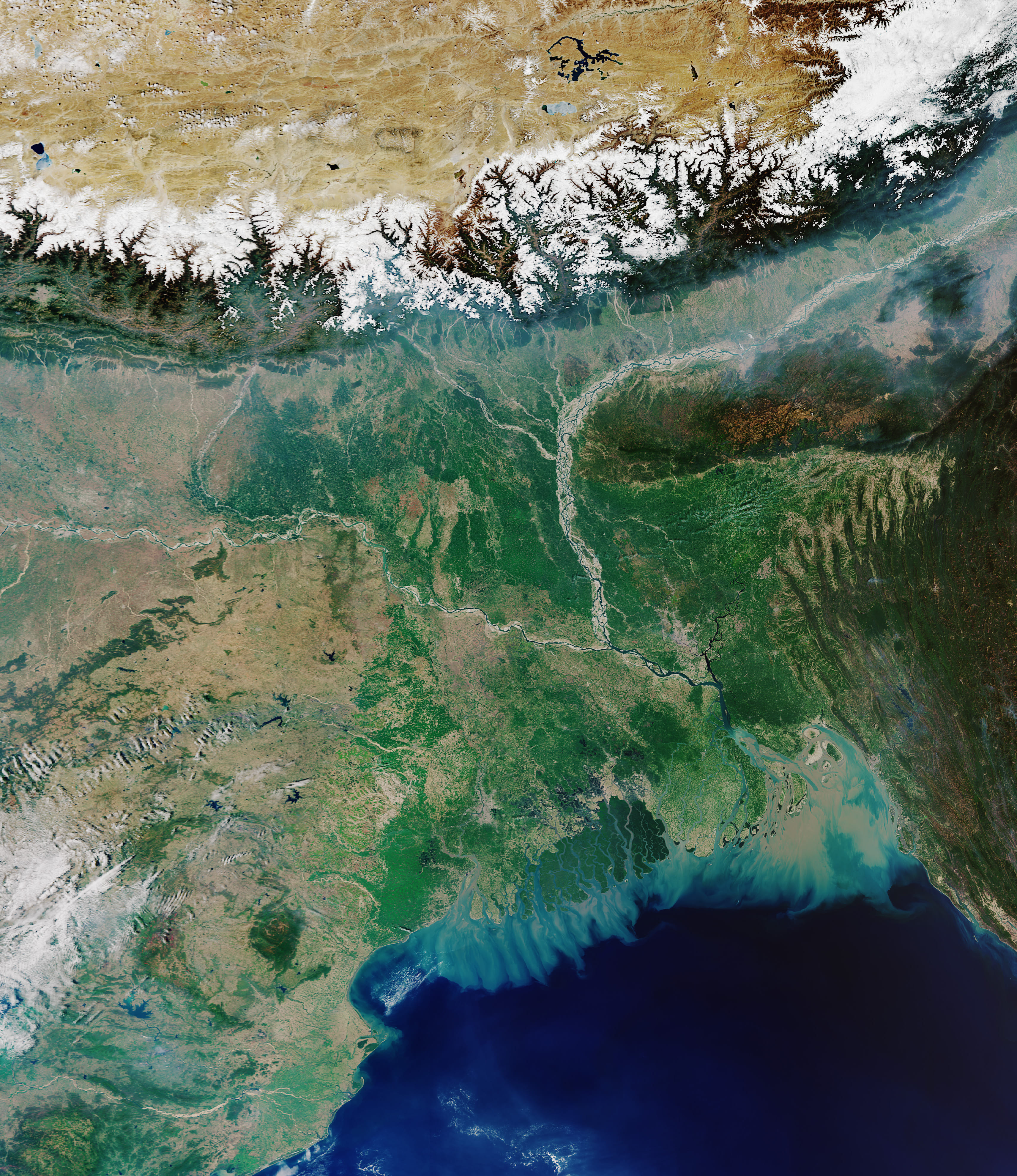

But I want you to imagine a time long ago before the Miocene Epoch, almost 140 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period, when the supercontinent Gondwana, located south of the equator, broke apart. The evidence of this violent period, which gave rise to the Indian tectonic plate, can still be found in the Rajmahal basalt and andesite stones a few kilometres below the surface of northeastern Bangladesh. About fifty million years ago, the Indian plate, like a Viking funeral ship carrying the fossils of dinosaurs and other fauna and flora, drifted northward and started to collide with the Eurasian plate. Over time, the sediment from the Deccan Mountains built up a delta on its eastern margin, but the Himalaya Mountains had to rise for the initiation of the Bengal Delta and the formation of the Ganges–Padma–Meghna river system.

As the Indian plate pushed northward over millions of years, the Tibetan Plateau rose much higher above sea level, initiating an intense monsoon system. This, in turn, gave rise to numerous rivers that ran from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal and to the Arabian Sea. The Ganges initially possibly flowed westward into the Arabian Sea. During the Miocene Epoch, about 15 million years ago, the Aravalli Hills in western India impinged northwards to partition the Himalayan foreland into east- and west-flowing rivers, thus forcing the course of the Ganges eastward. The palaeo Ganges–Padma likely entered the Bengal Foredeep just north of the Rajmahal Hills in eastern Bihar, the route that it maintains even today. At that time, the sea was located southeast of the so-called hinge zone—the line where the Indian continental craton meets the oceanic crust. This hinge zone runs south from the Rajmahal Hills to the Shillong Plateau, passing through Kushtia, Pabna and Tangail, before connecting with the Dauki Fault in northern Mymensingh and Sylhet.

At the hinge zone, right under the upper Padma, the continental crust dives almost five kilometres downwards to meet the oceanic crust. At the same time, there is evidence that an ancient Brahmaputra River entered the Bengal Basin through the Sylhet Depression, east of the Shillong Plateau. It is only within the last few million years that the uplift of the Shillong Plateau forced the Brahmaputra to change its course towards the west. Both these palaeo rivers emptied into a sea that bordered Sylhet and Mymensingh to the north, and Rajshahi to the west, bringing sediment onto the oceanic crust to establish the foundation of the Bengal Delta. It required more than 20 million years of intense sedimentation, over a deposition area of more than 100,000 square kilometres and up to a depth of 20 kilometres, to build the Delta. During this period, the land extended about 500 kilometres south from the Rangpur Saddle that separates the Bengal Foredeep from the Himalayan Foredeep.

About three million years ago, the Earth started to experience a regular ice-age cycle with periods between 100,000 and 150,000 years and interglacial intervals of 15,000 to 50,000 years. During the ice-age periods, the sea would retreat, and the rivers would cut gorges into the Delta and carry sediment directly to the ocean without depositing much on the land. It was only during the interglacial intervals that the Delta would grow through flooding and sedimentation. Since the last glacial maximum, about 18,000 years ago, the Delta has been in another growth stage.

What builds a delta? Rivers flooding their banks deliver sediment that keeps delta plains elevated above sea level. Over time, the weight of overlying sediments compresses the layers below, squeezing out water and causing the land to sink. This subsidence may also occur due to tectonic shifting of the underlying ocean crust and water withdrawal by humans. The sinking land allows floods to occur and fresh layers of sediment to be laid down; this mechanism keeps the delta plain always very close to sea-level height, even as deltas expand. During the last glacial maximum, the Bangladesh coastline was situated approximately two hundred kilometres south of the modern coastline. Since then, the sea has risen about 120 metres, submerging much of the land. After a series of advances and retreats, the modern Bengal Delta started to emerge about 7,000 years ago.

This history reveals a fundamental truth: a delta has an intrinsic relationship with sea-level rise. As contradictory as it may sound, it is during interglacial periods, when sea levels rise, that the Delta is replenished and expands. A delta can never rise very high above sea level. If it becomes too elevated, flooding stops and no new sediment is deposited. When excessive flooding raises the land, it subsequently sinks due to subsidence, and only the next major flood brings more sediment. Therefore, the fundamental characteristic of a delta is to remain close to sea level.

Understanding the delta’s nature helps us make sense of its history. There is considerable debate among specialists and non-specialists about whether the Hooghly, flowing through West Bengal, or the Padma is the original continuation of the Ganges. I think this debate misses the point that river avulsion is necessary to build a delta. The city of Kolkata and the modern confluence of the rivers Padma and Jamuna sit on ten kilometres of sediment deposition. This can only happen if the Padma changed its position hundreds, if not thousands, of times since the inception of the Delta. The avulsion timescale of the major rivers in the Bengal Delta is about 2,000 years. This means a river like the Padma would fill its basin, with an extension of 150 kilometres to 200 kilometres, within a few thousand years before changing its course.

There is evidence that the main Ganges–Padma flow has diverted towards the east over the last 10,000 years, flowing through the Hooghly, Gorai and Arial Khan, and finally settling into the current Padma–Meghna flow. I would argue that for most of its existence, the Padma, after emerging through the Rajmahal Hills, flowed east (possibly through the Atrai Basin/Chalan Beel area) and then turned sharply south to meet a deep submarine canyon called the Swatch of No Ground. In this canyon, just 60 kilometres south of Dublar Char in the Sundarbans, the sea floor gradually drops from 20 metres to a depth of one kilometre over a distance of 100 kilometres, whereas the sea floor on the sides of the canyon remains high, dropping to a depth of approximately 200 metres over the same distance. It was during multiple ice-age periods in the last few million years that the Ganges–Padma river system carved out this deep canyon. These were periods when the sea retreated, exposing land a few hundred kilometres south of its current position. Currently, the Swatch canyon serves as a conduit for the transfer of coastal sediment towards the deep sea. But this ancient geological story is not over. The delta is still being built—and the question facing us today is whether it can survive what comes next.

The Delta’s future

Water from five countries—India, Nepal, Bhutan, China and Bangladesh—covering 1.75 million square kilometres across the Himalayas and their foothills flows through the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna river system into the Bay of Bengal. Although this Himalayan watershed is smaller than the Amazon and Congo river basins, the enormous sediment flow—more than one billion tonnes annually—has created the world’s largest delta. Of this, about 40% has historically been deposited in the delta plain, 45% in the subaqueous delta, and 15% in the deep sea. It ranks among the highest sediment-carrying river systems in the world. In the western region near the Meghna estuary, delta formation through river-borne sediment is still active, while in the Sundarbans it is maintained by tide-borne sediment. North of the Sundarbans, the delta is essentially moribund.

Currently, based on tide-gauge and satellite data, the estimated global average rate of sea-level rise is just above four millimetres per year and is increasing slightly every year. This acceleration is expected to grow, with some studies estimating that global coastlines will experience close to one metre or more of sea-level rise by 2100. To correctly estimate the effects of sea-level rise on the Bengal Delta, researchers construct scenarios that include sediment analysis, dating techniques, and modelling of water and sediment transport. These simulations show that about 9,000 years ago, the sea transgressed all the way to the current location of Dhaka. This transgression allowed for new deposition, resulting in the modern Bengal Delta. Extending this simulation to a hypothetical scenario of a two- to three-metre sea-level rise, our estimates suggest that approximately 14% of Bangladesh’s land area would submerge, whereas other researchers have projected higher figures.

However, these long-term projections tell us little about the delta’s behaviour in recent decades. The high sediment accretion currently observed at the Padma–Meghna estuary was not predicted by these same long-term models, as they did not account for sudden increases in sedimentation caused by upstream upheavals. It is estimated that over the last 7,000 years, the Bengal Delta has expanded at a mean accretion rate of about five square kilometres per year. Several studies using historical charts and satellite images show that in the lower eastern Delta, sediment accreted at an average rate of about five to ten square kilometres per year during the 19th and much of the 20th centuries. The average accretion rate, however, increased to almost 10 to 20 square kilometres per year towards the end of the 20th century, a trend that appears to be continuing. Researchers suggest that this increased rate may result from multiple earthquakes, intensive land use, enhanced agricultural practices, and the restriction of sediment deposition caused by embankments.

Recent studies offer conflicting views on whether sedimentation can keep pace with sea-level rise. Some researchers have found that in the delta west of the Padma–Meghna estuary, sediment builds up at rates exceeding two centimetres per year—double the rate of local sea-level rise. Even accounting for land sinking, they conclude that accumulation reduces the risk of coastal flooding in the central lower Bengal Delta. After Cyclone Aila in 2009, when embankments failed, newly reconnected landscapes received tens of centimetres of sediment—decades’ worth of normal buildup arriving in a single storm. Studies of the Padma–Meghna estuary suggest that for predicted sea-level rise of 60–100 centimetres over the next century, vertical accretion could keep pace. The pattern seems clear: where rivers meet tides, where embankments break and water flows free, the delta rebuilds itself.

Yet many experts remain sceptical. The sediment flux reaching coastal areas, they argue, may not be enough—particularly given sedimentation’s variable nature, especially when dams built upstream restrict sediment flow, and in the face of accelerating sea-level projections. They call for extensive data collection on sedimentation, land sinking, river flow, and sea level to establish reliable patterns. Some climate models predict monsoon intensification that might enhance sedimentation, but this remains uncertain. What we do know is this: the delta is not a museum piece. It is still being formed, still reaching towards the sea. And for it to survive, sediment must flow unhindered from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal.

To understand what is at stake, we might look back to when humans first encountered this delta. About fifty thousand years ago, a band of humans left Africa, crossed the Red Sea, traced the Arabian Peninsula, and then followed the Indian coastline to stumble into the jungles of the Bengal Delta—a landscape vastly different from today’s. They might have seen shal, garjan and mango trees, as well as Sumatran and Javan rhinoceroses roaming near the wetlands bordering the Padma. The rhinos might have shared space with powerful aurochs, the ancestors of modern-day cattle. The humans might have seen giant-toothed stegodons, the ancestors of modern-day elephants. Tigers were still not there, only beginning their entry onto this land from the north, from China. These ancient humans might have seen and heard the roaring Padma making its way into the Swatch of No Ground canyon. They had to cross it on their way to Australia.

That delta—volatile, powerful, indifferent to human presence—is the same delta we live on today. The delta they encountered is the same one that subsided, advanced and retreated, drowned and re-emerged. We can learn from the geological prehistory of the Bengal Delta how to help sediment keep pace with the rising sea. For that, we need to allow the rivers to do what they have always done: flood, meander, build. The delta asks only that we not stand in its way.

Dipen Bhattacharya is a California-based writer and retired professor of physics and astronomy. His work spans fiction as well as writings on Bangladesh’s geological history and astronomy.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.