A Social Vision for Dhaka’s Housing

In this bustling and burgeoning city of Dhaka, home to 23 million and counting, nearly half a million people pour in each year, seeking economic opportunities and relief. With each arrival comes a singular, urgent requirement: shelter. Housing is the broad term for that need, something not confined to migrants alone. Within the city itself, as families expand and generations come of age, the quest for independent living quarters becomes another pressing issue. The growth of a city is the most vivid manifestation of this twin phenomenon.

As we once noted, "Housing is a complex social and economic dynamic whose results are the physical patterns of cities and settlements, the qualities of collective living, and the health and well-being of the people… it is the key to enhancing the quality of life of the dwellers and their city." Yet today, housing in Bangladesh stands not as a measure of dignified living but evidence of systemic omission. The promise of shelter, enshrined in our constitution as a duty of the state, is broken in plain sight.

This is not just a policy failure—it is a moral one. We have failed to address not only the basic human need for accommodation but also the question of how we should live together, how we should share land, resources, and the city itself. What is being built is not an arrangement of inclusion, but a fabricated inequity distributed across the urban landscape.

Housing has been central to the agenda of the modern city, in how the leaders of modern architecture and planning imagined a just and healthy society. It is the provision of housing that distinguishes the modern city from the premodern one. The crisis of living conditions – congested and unsanitary dwellings in late nineteenth century Europe – led to a zealous focus on reimagining the very fabric of the city, and rearranging the nature of dwelling. For modernist architects of the 1920s and later, housing remained a rallying call for pursuing a humanist and equitable society.

Since then, housing has been an abiding topic for many social and political leaders. As the late Aga Khan, a leader in some major architectural and development initiatives, noted: "The lack, and the deterioration of human habitations, as economics grow, urbanisation accelerates and demographics explode, pose some of the greatest practical and ethical problems that developing countries face." In the context of national developments, housing is a critical factor influencing the quality of human life, health and human safety. The Aga Khan emphasised that housing is not just a numerical and fiscal matter, it is about enabling the human spirit.

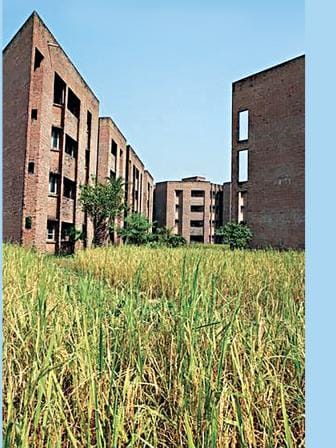

In Bangladesh, housing remains a mirage, a morichika. A much-bandied word, housing is pursued but not obtained, talked about but not realised. Far from addressing the needs of accommodation and elevating the human spirit, planners, economists, architects, engineers, policy makers and developers have failed to address this most fundamental human need. It is incredible that Dhaka with its megapolitan scale has faltered in making meaningful policies for socially oriented housing projects or delivering adequate affordable and worthwhile dwellings.

The numbers are staggering. The UNDP reports that there is a housing deficit of 6 million units, projected to balloon to 10.5 million by 2030. 70% of that requirement is for affordable options. But the market produces barely 1% of what is needed. Nearly 80% of Dhaka's people are renters, unable to enter the housing market. About 1.8 million live in slum-like conditions. State policies and financial services offer little incentive or initiative to overcome these lags. In 2025, housing received just 0.6% of the national budget, less than a round figure in a nation crying for decent homes.

In the meantime, no meaningful residential models exist for the mosaic of people making up Dhaka city—whatever economic class they may be from. Public sector housing is unimaginative and limited. Motivated by the plot-to-apartment scheme, the middle income group is beholden to plot based planning, the only option offered by RAJUK and private developers. The limited and lower income communities, for whom affordability is the most critical factor, have been completely ignored in the game of housing. Living in spontaneous and often extra-legal settlements, they make do with whatever resources they can muster by themselves.

The dominant urban model that goes for housing is mostly land manipulation by another name. Privileging the individual plot-to-apartment schema, the model centres around profit. Entire districts, from Uttara to Jhilmil, are shaped not necessarily by a housing need, but by, what some call, a "plot banijjo". This model is not only outdated for a dynamic city as Dhaka, it is also predatory in nature. It inflates land prices, decimates ecology, ravages wetlands, displaces communities, and, all the while fails in its basic role: to house a vast majority of the population.

How should we then pursue housing? The way forward begins with rejecting the idea that housing is just a numerical or logistical issue, and that it can be resolved by disbursing small plots. We have to be more imaginative and creative in facing the larger scope of housing, its cultural, communal, and ecological dimensions.

Housing is not just numbers. Housing is far more than numbers, though they matter. They help us grasp the scale of the crisis – the yawning gap between what is needed and what is built and what is available. In Dhaka alone, the city requires an estimated 120,000 new housing units annually. Yet, year after year, only a fraction, barely 25 to 30 percent, is delivered. In the face of this chronic shortfall, and in order to accelerate construction and close the deficit, architects, engineers and builders need to turn to industrial innovations: precast systems, modular housing, and rapid-build technologies. In more recent times, the "million houses" programme, whether in Indonesia or Sri Lanka, exemplifies government initiatives to reduce backlogs and provide housing for lower income groups.

While numbers highlight the urgency of housing, they do not capture its essence. Considering that housing is a social vision, the solution is not in the multiplication of physical units alone. Housing is more than a basha (house), it is about bashati—the shared space of living. That space is not only where we sleep, but where we live, relate, belong, and thrive.

Housing is the fabric of the city. Housing is the city. And the city is a reflection of its housing—its forms, its values, as well as its shortcomings. In reimagining one, we reinvent the other. How we envision a city directly impacts its housing in which density and liveability are crucial factors. From tall towers to dense habitats and scattered settlements, a city is made of an aggregation of housing forms reflecting the diversity of social and economic groups catering to different communities and their interests. On the other hand, the web of spaces in a housing reflects a miniature city, from the unit to the cluster of units, to the pathways and the social or community spaces, and the streets that connect it to the arteries of the city. If there is an architecture of housing, it is about how an intricate chain is formed from the inner sanctum of a house to the domain of the public. The old form of "paraa", which has almost disappeared from our midst, defined such a socially integrated network of lived spaces. Consequently, the design of housing involves a planning of neighbourhoods.

While the topic of housing assumes a magnified scope in regards to urbanisation and the expanded movement of people, there is also an urgency in rural areas. There, the challenge is to rethink the clustering of villages and homesteads in order to avoid the increasing conversion of agricultural lands and to generate a new kind of urbanised sociality. Safe and healthy housing is also needed in climatically vulnerable areas.

Housing is a key in a developmental context. Considering how resources are allocated in the city, in how land is apportioned and monetised, and how financial institutions organise loans and interest, housing is integral to the modern political economy. In Bangladesh's fast-growing economy, housing should be a pillar of both economic stability and public well-being, influencing everything from productivity to quality of life. In prioritising an economic agenda, we should not forget that for a city like Dhaka, housing is also a geographic matter. The relentless landfilling spurred by the development drive for planned residential areas is only the flip side of the economic programme. What we desperately need is a vision that unites the economy with ecology, and a sustainable and inclusive urban future with development programmes.

Housing has many forms and processes. Housing can take many forms, both in terms of a physical fabric and how it is produced and organised. It can be a collection of houses forming a "paraa" in a town or village, and it can be blocks or superblocks in a metropolis.

In its formal avatar, housing is a packaged product—designed, built, and sold within the marketplace, tailored by developers to match targeted income groups. Affordability is often engaged through subsidies or quotas, as seen in models where state land is leased out for private projects with provision for lower-income units. The question of equity, affordability and accessibility will remain key concerns in any housing initiative. Who gets to live where? Who gets to choose? And who gets left behind? We name-drop Singapore as a gold standard of economic brilliance, yet rarely pause to examine the elaborate, state-led system that ensures housing access for all through deeply planned policies and financing mechanisms.

Beyond the rigid market, housing is reclaimed as a living, breathing process—not a commodity delivered, but a right slowly assembled by people themselves. In these contexts, exemplified in the legendary work of the Egyptian architect Hasan Fathy in the village of Gourna in the 1940s, people build their homes not just with bricks, but with agency. Given the basics—land access, utility lines, perhaps a toolkit—they raise dwellings that evolve with their lives. Here, housing becomes a verb, as famously observed by the housing guru John F.C. Turner. Agency is not just a legal impetus but an existential drive, as community members, often women, become designers, builders, and stewards of their own environments.

What are the alternatives? Beyond a handful of notable cases—from Muzharul Islam's group housing of the 1960s–70s to Khandaker Hasibul Kabir's current self-help projects—innovative housing in Bangladesh remains few and far between. What we urgently need are compelling models across all types: social, affordable, cooperative, and participatory. We must move beyond the fragmented plot-to-apartment formula and reimagine housing as a group form at the block scale, where diverse unit types, density, liveability and community spaces will matter. Like Berlin's 1987 International Building Exhibition, where visionary architects built experimental neighbourhoods and housing blocks, Dhaka too can become a laboratory for new urban living.

At Bengal Institute, we have explored new possibilities and prospects of the housing block. Offering a more inclusive and efficient model, 6–8 adjacent plots, say in Uttara or Purbachal, can be consolidated into a single integrated housing complex with shared courtyards, amenities, and open spaces. The current Dhaka DAP rightly promotes this "block housing" typology, which should become the default planning unit across the city. A network of such blocks can generate new public realms and a refreshed urban fabric.

In the conflict between ecology and economy, we have developed ideas for new forms that present a mediation. We have conceived housing forms and clusters that cooperate with our hydraulic environment. We proposed an "edge-form" housing—a linear band around wetlands and floodplains that preserves ecosystems while addressing decent homes and economic drives. Similarly, Dhaka's expanding metro rail corridors and their stations are ripe for transit-oriented housing, where density is shaped around mobility and access.

Housing is and will remain a social responsibility—it is a public mission. If this is an era of reform and equity, then housing must be in the foreground, whether delivered top-down, built bottom-up, or co-created in partnership.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf and Nusrat Sumaiya are architects, and direct the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments