In search of Rajnagar: A city devoured by the Padma

While human settlements have originated on the banks of rivers, the landscape of Bangladesh is a vast graveyard of cities and villages, as noted by architect and writer Kazi Khaleed Ashraf. Catapulted into tempestuous rivers or slowly eroded by their treacherous movements, the cities of Bengal have always been at the mercy of its rivers. The most powerful and capricious of them all is, of course, the Padma. Whiplashing along its banks, especially as it nears the confluence with the Meghna, the Padma has devoured an untold number of villages and settlements, upturned countless lives, and then, in some compensatory way, laid over the same drowned settlements new silt and sand, almost as if on a clean slate. Of all the settlements on the Padma's hit list, the most fabled are Rajnagar and Japsa.

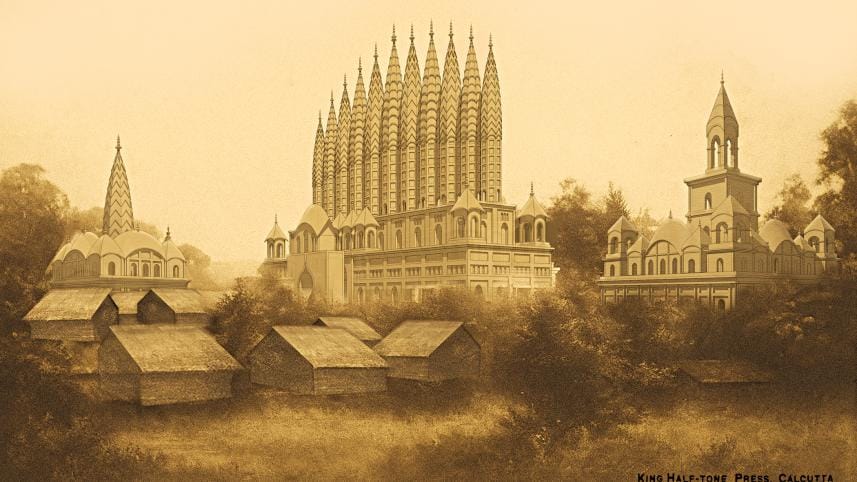

Rajnagar was a settlement adorned with grand temples, palaces, gateways, large water tanks, festive grounds, and bustling bazaars – its architecture was unique and original even in the context of the entire subcontinent. Once a symbol of pride, the nagar was gradually washed away by the Padma. The tale of Rajnagar is about a vanished city and the tandab unleashed by Bengal's rivers. Yet the story of Rajnagar is not merely one of disappearance; it is also a story of Bengal's architecture and heritage, which we hope to retrace.

Rajnagar was situated in southern Bikrampur, specifically near the present-day Zajira area of Shariatpur district. Before Rajnagar, this area was known as Beel Deonia, a name that still survives. Using the location of Rajnagar on English cartographer James Rennell's map of 1777, geographers at the Bengal Institute place it somewhere in the northeast of present-day Shariatpur.

Established by Raja Rajballabh in his birthplace, Beel Deonia in Bikrampur Pargana, Rajnagar was later developed by his son and grandson. According to documents and descriptions, the town was rich in architecture, featuring wondrous buildings and tanks. The most notable structures were temples with high spires known as ratna or 'jewels,' visible from the Padma River. The English cartographer James Rennell, in his journal chronicling his riverine journey from Calcutta to Dhaka in 1764, mentioned spotting multiple-spired structures – what he called the "pagodas" of Rajnagar. Among these, described in various texts, were nine-spired, five-spired, seventeen-spired, and the most famous twenty-one-spired buildings, or the ekobingsho ratna. A visual reference of the twenty-one-jewel structure appeared in the book Pundra Nagar to Sher-e-Bangla Nagar: Architecture in Bangladesh (1997, edited by Saif Ul Haque, Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, and Raziul Ahsan). The image was a sketch made by Joseph Scott Philip in 1833.

Son of Krishnajiban, Rajballabh was born in Beel Deonia in 1707. He began his career as a muhuri in the Qanungo division of the Mughal administration. In 1756, he became the dewan of Dhaka under the Mughals and was granted the title of Maharaja. As an accomplice of Ghasheti Begum and Mir Jafar in the power struggle against Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula, he acquired an ill repute. Like Rajnagar, Rajballabh too met a watery end when Mir Qasim reputedly had him drowned in 1763. Though Raja Rajballabh is portrayed as a controversial character in Bengal's history, his Rajnagar remains a unique example of innovative regional architecture and urban planning.

In its present-day location, Beel Deonia lies on the south bank of the Padma River. When Rajnagar was established, the Padma flowed further to the west. From Rennell's map, we can infer that the Arial Khan River channel was one of the main courses of the Padma, and the confluence of the Padma and Meghna rivers was then located further south, near Mehendiganj in Barishal district. The Padma there flowed as a smaller river. Although Rennell marked it as the Kaliganga River on his map, historians such as Jatindramohan Ray argued that it was the Rothkhola River. South of Rajnagar, a river ran from the south-west to the east. From Rennell's map, we can see that one mouth was located at Chekondy and another near Mulfatganj; however, no name was assigned to it. It may be the present-day Palong River, which has also undergone reshaping. When the Kaligonga or Rathkhola River became the main course of the Padma, it began eroding both banks. On the north bank, there were also some establishments by Raja Kedar Roy, one of the twelve baro bhuiyans. Destroying these establishments, the river acquired the name Kirtinasha (destroyer of human achievements). After ravaging the north bank, Kirtinasha gradually engulfed the Rajnagar area from the south bank.

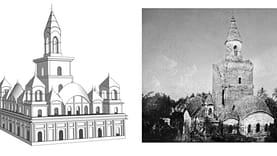

In describing the architecture of Rajnagar, the twenty-one-spired building stands out as the most unique. Erected by Raja Roy Gopalkrishna, the fifth son of Rajballabh, the structure was in fact the main entrance to the palace compound. The three-storey building had chambers for soldiers on the ground floor, and the first-floor chambers were for musicians who used to play morning ragas from there. This remarkable building, not quite a temple, was a composite of features from traditional Bengali temple architecture. It featured an "ek bangla" (chala) roof on the gateway, ten ratna-type small chambers, and, most remarkably, eleven math-like spires at the top, forming a bow that could be seen from a great distance.

The Rajnagar palace complex had multiple yards. The Saptadash Ratna temple was in the third yard. It was a Dol Mancha used for Dol festivals. As a mancha, pavilion-like structures are seen in Bengal in a variety of forms, from the simplest pavilion to complex multi-storeyed ones such as the Dol Mancha in Rajnagar. The Dol Mancha was called the Saptadash (seventeen) Ratna temple as it had four storeys and 17 jewels or ratnas.

On every Basanti Purnima, the idol of goddess Lakshmi-Narayan was taken from the Pancharatna Temple and placed on the topmost pavilion of the Saptadash Ratna on the golden throne. This procession carrying the idol was called Dol Jatra. At Rajnagar, this was a famous and significant festival. From Rasik Lal's description, we get a vibrant picture of the celebration. People used to wear beautiful dresses called basanti and play with red-coloured dust.

The structure of the Saptadash Temple was very high. There were more structures of such height in the complex, but the Saptadash Temple was the only one that was accessible from the highest floor. Its pinnacle could be seen from the other side of the Padma River. People used to follow it as a landmark for crossing the river.

In addition to its fascinating structures, Rajnagar also had numerous large tanks and reservoirs. The largest one was called Rajsagar; there was a saying that it was so big that one could not hear gunfire from the other side. Another notable location adjacent to Rajsagar was known as Old Dighi. A significant and famous festival known as Kalboishakhi Mela was held for two months on the west bank of the dighi. The largest Charak Puja and festival of Bengal was also held there.

A Nabaratna Temple was located in the old haveli or building complex beside the famous Old Tank. This old complex, which once housed the tank, was the residence and homestead of Krishna Jiban Mojumdar, the father of Rajballabh, who established the complex and also erected the Nabaratna before the place became Rajnagar. The Nabaratna is a two-storey building with a square plan. On the first floor, there were eight small chala structures known as jhitki ghar and one high spire known as math. All structures had ornamental peaks, known as ratnas. For these nine structures with peaks, the building was known as Nabaratna or the nine-peak, or jewel, building. Krishna Jiban Mojumdar's old complex was the last one destroyed by the river Kirtinasha, and the Nabaratna was the last building to fall.

The Pancharatna Temple was situated on the same campus as the Saptadash Ratna Temple. The name Pancharatna, or the five jewels, indicated a large Bengali chala structure in the centre, and four jhitki ghar or small pavilion-like structures in the four corners. Compared to other Pancharatna structures, which typically have one large jhitki ghar as the ratna, a centrepiece in the middle of the roof, the Pancharatna Temple in Rajnagar had a large Bengali chala structure as its central pavilion. This characteristic makes this temple unique. Across the front yard of the Pancharatna was a building complex with an inner courtyard where Rajballabh used to reside.

The story of Rajnagar also includes the nearby complex at Japsa. Sometime in the 17th century, Bedgarbha Sen, a vaidya or physician, came from Jashore and settled in Deonia (now in Shariatpur). He had two sons. One remained in Deonia, while the other, Nilkantha, moved to the nearby town of Japsa. There, Gopiraman Sen, the great-grandson of Nilkantha and a khasnabis (private secretary) of a high official of Khas Mahal, built six palaces or havelis for his six children. From that, the group of buildings came to be known as the "Choy Habeli" of Japsa. The most famous structure was a high-spired one, known as Japsa Math, which was marked on James Rennell's map of Bengal. He also mentioned that it could be seen from both rivers. In later days, with Krishnaram's son Lala Ramprasad becoming famous, the complex also came to be known as "Lala-Bari". Masons from Japsa were very skilled and well known for the construction of maths and other building structures, and used to travel to various places in Bengal to construct buildings.

Japsa Habeli was a centre of education. There was a maktab for learning Farsi and a chatushpathi for learning Sanskrit. Raja Rajballabh came here at an early age to learn Farsi. Many poets and writers from this family were engaged in intense literary production. Lala Ramgati, son of Lala Ramprasad, wrote a Bengali poetry book, Mayatimir Chandrika. The daughter of Ramgati was known as Bidushi Anandamayi, who wrote Harilila (the story of Satya Pir/Satyanarayan) along with her uncle Jaynarayan. Jaynarayan also wrote Chandimagal in 1763.

Waterways were the primary means of trade, transportation, and social activity in Rajnagar. One of the prominent waterways in Munshiganj district was Taltola Khal, which connects the Dhaleshwari and Padma rivers. This canal still exists and is navigable during the monsoon season.

Rajballabh and his son Ramdas used this canal as the main route for travelling from Dhaka to Rajnagar. Some historians believe Rajballabh excavated it for this purpose. Others suggest that Rajballabh merely made it navigable, the canal being much older. Taltola Khal, which is nearly 13 km long, meets the River Padma at Dohori village in Louhajang, also known locally as Dohori Khal. The other end meets a branch of the Dhaleshwari River at the Taltola Bazar point. James Rennell, during his expedition, used this canal at a time before the Kaliganga River became Kirtinasha and destroyed Rajnagar. From his documents, we learn that he entered this canal from the Nullua-Kaliganga junction, which no longer exists. He marked Taltola point at Mirganj, which remains the name of a village today. His budgerow went underneath an old brick bridge, which was later destroyed by the East India Company to allow larger mercenary boats to pass. On the eastern bank, he marked a 'pagoda'. Possibly, this was the Pancharatna Temple, established by Rajballabh, which is now lost. It was said that he or his son Ramdas, starting from Rajnagar at night, used to reach here by dawn and perform Sandhyavandana. He dedicated 300 bighas of land for the maintenance of this temple.

Rajnagar might have disappeared, but its legacy endures through poetry, maps, and historical documents, and remains a significant part of Bengal's architectural and cultural heritage. Although there is no photograph of any of the Rajnagar structures (except a historic one of the famous seventeen-jewel temple published by Philip Thornton recently on his Facebook page), there exist some simple hand-drawn depictions and sketches of different structures. We have tried to reconstruct the visuals of those structures in new drawings and present them here for the first time.

Hassan M. Rakib is an architect and coordinator of design projects at the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements. Prof. Kazi Khaleed Ashraf provided guidance in the research.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments