Continuing brutality at the Bangladesh–India border

"Indian security forces pushed me over at gunpoint. I spent two days without food or drinking water. I was in the middle of a field in knee-deep water, teeming with mosquitoes and leeches."

— Shona Banu, 58-year-old Bangla-speaking Muslim woman who was forcibly pushed across the border by the Indian Border Security Force. (Al Jazeera, DW News, 2025)

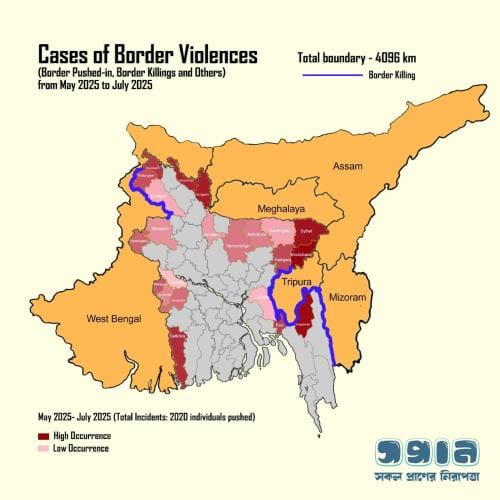

Shona Banu's harrowing account lays bare the brutal reality endured by thousands along the India–Bangladesh frontier. In recent months, the Border Security Force (BSF) has not only carried out killings of Bangladeshi civilians with impunity but has also engaged in unlawful abductions and forced "push-ins" of Bengali-speaking Muslims — many of them verified Indian citizens — without recourse to any due legal process. The 4,096-kilometre border has thus become a theatre of violence, marked by systematic human rights violations that brazenly flout bilateral agreements and international law.

Between May and July 2025 alone, India reportedly pushed back 2,020 Bengali-speaking Muslims, alleging illegal entry without presenting substantial evidence. Many of those expelled insist they are Indian citizens who have lived in the country for years. Such practices represent a systematic dehumanisation of Muslim communities, particularly those of Bengali ethnicity, and threaten to ignite a grave humanitarian crisis along the borderlands.

Fifty-one-year-old schoolteacher Md. Khairul Islam, from Assam, recounted to the BBC:

"I said, I won't go. They beat me up, tied my hands, and blindfolded me. They told me to keep quiet."

According to his wife, Rita Khanam, he was taken by Indian police late at night. Although declared a foreigner by an Assamese Tribunal in 2016, his case is still pending in the Supreme Court. After two weeks, he managed to return home, but only after being stranded in No Man's Land for at least four days without food or clean water.

Abdul Latif, aged 62, has been missing for several days after being accused of being an illegal Bangladeshi. His daughter suspects that he too was pushed into Bangladesh. She expressed her grief to the BBC, stating:

"My father is an Indian, not Bangladeshi. He's not a toy you can toss from here to there. He's a human being with rights."

No legal deportation procedures were followed in his case either.

Samat Ali, an elderly man whose name was included in the NRC, was still expelled from his homeland, underscoring the arbitrary nature of the expulsions.

Between May and July 2025 alone, India reportedly pushed back 2,020 Bengali-speaking Muslims, alleging illegal entry without presenting substantial evidence. Many of those expelled insist they are Indian citizens who have lived in the country for years. Such practices represent a systematic dehumanisation of Muslim communities, particularly those of Bengali ethnicity, and threaten to ignite a grave humanitarian crisis along the borderlands.

India's current push-in operations echo earlier practices, most notably the 1992 "Operation Push Back," which deported 132 individuals and drew international condemnation. Yet today's expulsions are without precedent in both scale and frequency.

The impact of this violence extends far beyond the immediate fatalities. Families are left to grieve in trauma, livelihoods are shattered, and an atmosphere of fear has come to define everyday life in border communities.

Escalating trends of border violence

According to the human rights organisations Odhikar and Sapran, between 2010 and July 2025 a total of 534 Bangladeshi citizens were killed and 1,265 injured by the BSF.

It has been alleged that a disturbing new trend in these killings has emerged. The BSF is no longer simply shooting on sight; instead, it has begun altering its tactics to conceal the scale and brutality of its crimes. In the past, residents of border areas were typically shot dead, but recent reports reveal that Bangladeshis are now being tortured to death in different ways.

In a recent case, on August 2, 2025, the bodies of two Bangladeshis were recovered from the Padma River near the Masudpur border in Chapainawabganj. Locals alleged that the men were tortured and killed by the BSF. A member of the local union parishad further claimed that the corpses bore signs of brutal torture, including acid burns and deep cuts from sharp weapons. He explained that the two men had crossed into India two days earlier to bring back cattle and had been missing since then.

Violations of international and domestic legal norms

The BSF's lethal border practices — including "push-in" operations and excessive use of force — amount to prima facie violations of both International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL).

The BSF has been expelling Bangla-speaking individuals, verified Indian citizens, and refugees without verification, legal recourse, or procedural safeguards. Such collective expulsions contravene well-established international norms, codified in Article 13 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 22(1) of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. These provisions mandate individual assessment, adherence to agreed repatriation procedures, and access to judicial review — standards India is disregarding.

These actions also breach the right to seek asylum under Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and violate the principle of non-refoulement, a cornerstone of refugee protection under customary international law and Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Particularly concerning are reports of Rohingya refugees being forced into unsafe conditions, including open waters, in direct affront to human dignity.

India's current push-in operations echo earlier practices, most notably the 1992 "Operation Push Back," which deported 132 individuals and drew international condemnation. Yet today's expulsions are without precedent in both scale and frequency.

The BSF's long-criticised "shoot-on-sight" policy raises further alarm. International law allows lethal force at borders only when absolutely necessary to protect life. Under Article 6 of the ICCPR, the right to life is non-derogable, while Article 7 of the ICCPR and Articles 1 and 16 of the Convention against Torture (CAT) strictly prohibit torture. Incidents of torture, killings, and other inhuman treatment by the BSF clearly breach these protections, as well as the guarantees of liberty and security under Article 9 of the ICCPR.

Bangladesh has reiterated its willingness to repatriate verified nationals through bilateral procedures. India's circumvention of these processes not only violates international law but also erodes trust and undermines the rule of law at one of the world's most militarised borders.

Why does India continue border violence?

The recurring acts of violence at the Bangladesh–India border are not random or isolated incidents but are symptomatic of a deeply entrenched culture of impunity, where certain communities are deliberately excluded from protection and justice. These repeated and arbitrary killings are not mere aberrations but instead represent elements of what has become, in practice, a permanent state of emergency.

As Hurd (1999) observes, when states of emergency are prolonged and repeated over time, they cease to be exceptional; instead, they are normalised into accepted traditions or even ritualised practices. The case of Felani's killing is emblematic of this systemic failure. More than fourteen years later, the absence of justice in her case demonstrates an ongoing disregard for human rights along the border.

The urgent need is for concrete measures to hold India accountable for its actions along the border — including the extrajudicial killings of Bangladeshi civilians and the unlawful pushback of Bengali-speaking Muslims from India.

Giorgio Agamben's notion of bare life provides a conceptual framework for understanding this border violence, particularly the illegal "push-in" operations. Modern states, while ostensibly established to safeguard citizens, repeatedly demonstrate the tendency to exclude certain groups from the political community, stripping them of rights and rendering them killable without consequence.

Equally relevant is Navine Murshid's concept of differential neoliberalism, which offers another powerful lens through which to interpret the brutality at the Bangladesh–India border. In the unequal political economy of South Asia, Bengali-speaking Muslims — whether Bangladeshi nationals or Indian citizens — occupy a paradoxical position: they are indispensable as low-wage labour yet simultaneously deemed politically disposable. This economic and political hierarchy, shaped by neoliberal reforms and intensified by ethno-religious nationalism, legitimises their exclusion from even the most fundamental rights: the right to life, to security, to due process, and to freedom from arbitrary expulsion.

The violence at the border thus cannot be reduced to territorial disputes alone; it reflects a deeper and more brutal politics of linguistic dominance. Under the BJP's ascendant Hindu nationalist agenda, Bengali identity itself is stigmatised as a marker of "otherness," exposing Bengali-speaking communities to targeted state violence and forced displacement.

India's institutionalised impunity is further demonstrated in the ongoing pushbacks and escalating violence. On May 30, 2025, Assam's Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma openly admitted to forcibly pushing people across the border, claiming these actions constituted deportations of individuals already declared "foreigners" by State tribunals, while citing Supreme Court orders (BBC News, 2025). On June 7, he went further by invoking the Immigration (Expulsion from Assam) Act of 1950, thereby empowering district collectors to bypass judicial review entirely and directly expel alleged foreigners. This escalation persists despite the fact that many expelled individuals appear on the 2019 National Register of Citizens (NRC), a deeply flawed exercise that excluded nearly two million people and compelled them to prove citizenship before Foreigners Tribunals (Human Rights Watch, 2025).

Finally, as Dr Ali Riaz, Professor at Illinois State University, told Al Jazeera, the surge in expulsions is directly connected to deteriorating Bangladesh–India relations following Sheikh Hasina's exile to India in 2024 and India's subsequent refusal to cooperate with the Dr Yunus-led government. According to Dr Riaz, India is strategically using displaced communities as leverage — both to exert pressure on Bangladesh and to create conditions of instability and potential clashes in the border regions.

Demand justice, end border atrocities: A human rights imperative

The illegal push-ins and killings at the India–Bangladesh border cannot be described as border management; they are outright violations of dignity and justice. Families abandoned in no man's land, deprived of food and water, or torn apart by forced expulsions deserve more than passing sympathy; they are entitled to truth, accountability, and redress. Justice demands independent investigations into push-ins and extrajudicial killings, prosecution of those responsible, and formal recognition of the victims.

The systematic reliance on illegal push-ins, combined with extrajudicial killings and the denial of due process, signals a profound collapse of justice at the India–Bangladesh frontier. These practices not only trample upon individual rights but also destabilise entire communities, rendering them stateless, displaced, and defenceless. Human rights organisations and activists must move beyond the passive documentation of abuses. The urgent need is for concrete measures to hold India accountable for its actions along the border — including the extrajudicial killings of Bangladeshi civilians and the unlawful pushback of Bengali-speaking Muslims from India.

Nusrat Jahan Nisu is a human rights researcher and development worker, currently serving as a Research Assistant at Sapran (Safeguarding All Lives).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments