Architecture in the living Bengal Delta

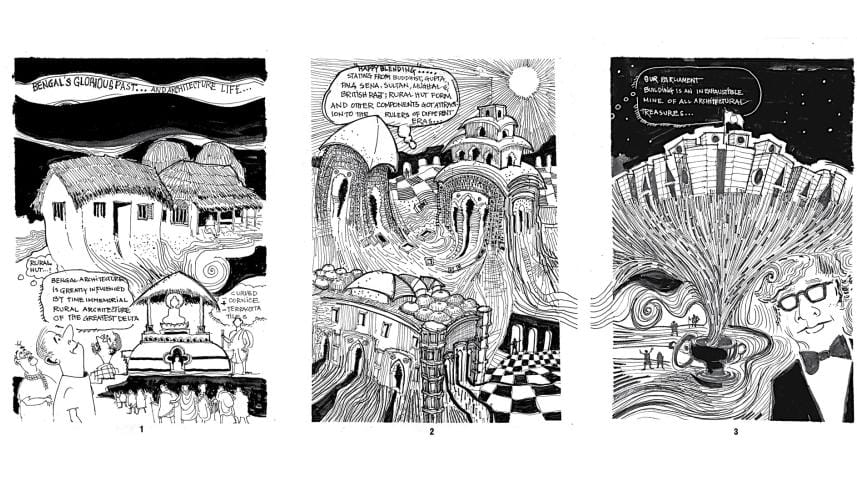

Bengal's deltaic landscape, nourished by the alluvial embrace of mighty rivers, has for centuries cultivated a unique and enduring architectural identity. Rooted deeply in geography, mythology, and climate, its built environment evolved through vernacular wisdom, where house forms, courtyards, and spatial orientations responded both to natural elements and to the spiritual beliefs of its people. This is the DNA of place—an architectural expression inseparable from the ecology of water, soil, and climate—where brick became the genetic material of form.

Over centuries, this fragile yet fertile terrain has carried the DNA of memory, a palimpsest of cultural imprints ranging from the serene geometry of Buddhist and Gupta structures to the sensuous terracotta idioms of the Sena period, from the austere elegance of Sultanate mosques to the imperial scale of Mughal complexes, and later the infrastructural legacies of British colonialism. Each epoch reshaped the architectural narrative while retaining an unmistakable cultural soul, resulting in a mosaic of forms that reflect Bengal's socio-political exchanges and cultural amalgamations.

At the same time, the region's architecture embodies the DNA of time—marked by resilience, transformation, and adaptation to floods, conquests, colonial interventions, and post-independence aspirations. The modern era witnessed a reawakening when pioneer architect Muzharul Islam led a critical regionalist approach that reconnected modern design with Bengal's traditions, while his invitation to the legendary Louis I. Kahn resulted in the masterpiece of the National Parliament House—today revered as the world's largest legislative complex. This monumental work, born of cross-cultural dialogue, crystallised centuries of architectural evolution into a timeless symbol of democracy.

This illustrated architectural theme, presented as a comic narrative, seeks to awaken a new generation of architects and thinkers to the wisdom embedded in Bengal's built heritage—not to indulge in nostalgia, but to search for solutions. For only by linking heritage with the present can we build a future that is sustainable, sensitive, and truly our own. Thus, the DNA of place, memory, and time in Bengal's living delta architecture becomes not merely a relic of the past, but a roadmap to creating a more humane and meaningful environment on Earth.

The delta of Bengal, shaped by the restless waters of the Ganges and Brahmaputra, has long been a crucible of culture, ecology, and imagination. Here, architecture has never been an isolated practice of walls and roofs, but a living dialogue with climate, myth, and memory. To understand Bengal's architecture is to trace the DNA of place, memory, and time—an inheritance written not on paper but in brick, earth, and water.

Vernacular wisdom and the birth of place

The journey begins with Bengal's rural vernacular. Plate 01 depicts the archetypal deltaic dwelling: mud walls, thatched roofs, shaded verandas, and central courtyards. These forms were not aesthetic accidents but ecological necessities—raised plinths resisted floods, sloping roofs shed monsoon rains, and open courtyards caught breezes in humid summers. This is the DNA of place: architecture born from geography, soil, and water. It reveals a language of intimacy and resilience where daily rituals, seasons, and community life wove seamlessly into spatial design.

Memory in clay and terracotta

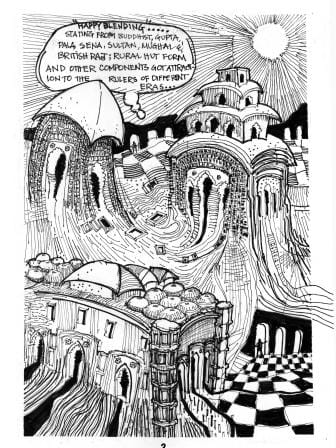

From the soil-bound vernacular, Bengal's architecture expanded into temples and monasteries that carried myth and ritual into form. Plate 02 recalls the exquisite terracotta temples of the Gupta period and the serene Buddhist viharas of Paharpur—structures that embodied the DNA of memory. Their walls were not mere enclosures but narrative canvases, inscribed with epics, folklore, and sacred motifs.

Later, the austere mosques of the Sultanate, the monumental Mughal complexes, and the infrastructural imprints of the British layered the land with new vocabularies. Each dynasty rewrote the surface of Bengal, yet never erased its cultural soul. Memory endured in brick and ornament, carrying the whispers of civilisations forward in time.

Modern awakening and the monument of democracy

If Bengal's past was a tapestry of place and memory, the 20th century brought the dimension of time into full force. Plate 03 turns to the post-independence era, when pioneer architect Muzharul Islam launched a critical regionalist approach—modernism grafted onto Bengali roots. His vision extended further when he invited Louis I. Kahn to design the National Parliament House, now revered as the world's largest legislative complex.

Kahn's Parliament radiates as a vessel of inexhaustible treasures, symbolising how centuries of architectural DNA condensed into a single, timeless monument. Here, democracy itself found expression in geometry, light, and brick—an architecture of permanence in a land of shifting waters.

Muzharul Islam and the language of modern Bengal

Plate 04 shines a moonlit light on Muzharul Islam himself, the pioneer of Bengali modernism. His works bridged the vernacular with the global, creating a language that was both rooted and forward-looking. The thought bubble in the sketch—"Architect and pioneer of Bengali modernism has greatly enriched our architectural treasure"—captures his role as a translator of memory into modernity.

In his hands, modern architecture was not an imported style but a continuation of Bengal's evolving story, carrying the delta's DNA into a new age.

Towards a future language of architecture

If the first four plates trace the inheritance of Bengal's architecture, Plate 05 looks forward. It asks: what language will future architects speak? Will they succumb to the homogenising pull of global styles, or will they craft a design vocabulary that resonates with the DNA of their land, its rivers, its rituals, and its resilience? The task for the next generation is not to replicate the past, but to reinterpret it. Just as terracotta once spoke of myth, and Kahn's Parliament embodied democracy, tomorrow's architecture must respond to the urgencies of climate change, urban growth, and cultural continuity. Plate 05 becomes a manifesto: the blueprint for a future where sustainability, sensitivity, and identity converge into a living architectural language of Bangladesh.

Glorious architectural life of the delta: A legacy carved in clay and spirit

The story of Bengal's architecture is not merely a history of buildings, but a living chronicle of a civilisation that thrived upon its rivers, rituals, and resilient spirit. The deltaic landscape, nourished by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and countless tributaries, nurtured a cultural ecosystem where architecture emerged not only as shelter but as a reflection of life, myth, and memory. The fertile alluvial plains gave rise to an architecture of earth, brick, and spirit—rooted in nature and guided by cosmic order.

The historical layers of Bengal's architectural narrative are profound. From the sacred geometry of early Buddhist viharas to the sensual terracotta temples of the Sena and Pala periods, from the introverted elegance of Sultanate mosques to the majestic urban imprints of the Mughals, each era left a distinctive vocabulary, yet all echoed the same soul of the land. With the British colonial intervention came new materials, institutions, and a redefinition of space and power, leading to confrontation and negotiation between the native and the imposed. This continuum did not break with time; rather, it matured and found fresh expression in the Bengali Modernism of Muzharul Islam, whose works were not just forms but philosophies, drawing the past into the present with conscious reverence.

Bengal's architecture is, therefore, a palimpsest—a surface rewritten through centuries, yet never erasing its origins. The courtyard-centric dwellings, shaded verandas, and humble thatched forms of the rural Barind or delta regions were not randomly devised; they were responses to climate, topography, and collective living. These homes were spiritual enclosures, where architecture became ritual, and daily life unfolded within sacred geometry.

In the modern context, as the nation moves towards urban expansion and globalised aesthetics, the forgotten methods of spatial planning, orientation, and material wisdom offer vital lessons. The past is not a burden here—it is a solution. The time-tested strategies embedded in Bengal's vernacular traditions—from passive cooling to community-centric planning—can inspire a more sustainable, humane, and culturally rooted architectural future.

Modern heritage, too, is part of this continuum. The works of contemporary architects must not reject the past but reimagine it through reinterpretation, abstraction, and ethical responsiveness. There lies the potential of a newness in architecture—a future that is not foreign but evolved organically from within our own soil.

This illustrated architectural discourse is thus not merely a nostalgic return, but a visionary attempt to reconnect the emerging generation with a lineage of built wisdom. Through the blend of visual storytelling and academic reflection, we aspire to cultivate a deeper awareness, so that the young architects and dreamers of this land can walk forward without losing sight of the path behind them.

To truly understand and shape the future of architecture in Bengal, we must first reconnect with heritage—not merely as preserved monuments, but as living methods. The soul of Bengal's built environment lies in the way its walls breathe with air and memory, the way courtyards shape light and life, and how rituals unfold within architectural rhythms. This inherited intelligence—silent yet profound—must be embraced as a vital method rather than frozen as an artefact. Reconnection demands that we decode how materials were sourced from the land, how forms grew out of both climate and culture, and how architecture once served as ritual, not just as shelter.

In this journey, we must also revalue vernacular logic as resilient science. What was once dismissed as 'rustic' now emerges as a sophisticated response to ecology and community. The homes of the Barind, the stilted shelters of haor regions, and the layered thresholds of Bengal's courtyards hold within them centuries of adaptation. These are not primitive solutions but deeply localised systems guiding us to build sustainably with what the land offers, and for those who understand its language. Revaluing this logic is an urgent act in a time of global environmental instability.

As we embrace these traditions, we must also reframe them through modern sensibilities and technologies. Tradition must not be embalmed—it must evolve. Through abstraction, reinterpretation, and innovation, Bengal's design language can be reborn in contemporary expressions. Parametric terracotta patterns, modular plans inspired by the courtyard logic, and climate-responsive technologies rooted in ancient wisdom—these can lead us into a future where modernity is not imposed, but emerges from within.

Yet, beyond function and form, architecture must also reclaim the spatial narratives of emotion, memory, and community. In Bengal, space was always storytelling. From mosques where echoes of prayer wove through domes, to porches where life unfolded with the seasons, architecture has held the rituals of daily life. Reclaiming these narratives means designing places that feel as much as they function—where buildings speak of identity, inclusiveness, and collective memory. It is through this reclamation that architecture becomes a vessel of belonging.

Ultimately, we must reimagine the future not as a break from the past, but as its mindful extension. Development must no longer be erasure, but dialogue—a continuity of culture across time. Every intervention should begin with the DNA of the place, layered with history and lived experience. This vision encourages us to see architecture as temporal layering, not stylistic rupture. The future must rise from the footprint of the past—enriched, not erased.

In conclusion, this architectural journey through drawings, narratives, and philosophical reflections is more than creative storytelling; it is a call for ethical remembrance. Let this work act as a recipe, blending material, memory, and meaning; a ritual, renewing our bond with the land and its people; and a roadmap, guiding future architects to design with identity, ecology, and compassion at heart. In the still-wet clay of Bengal, the past waits patiently—not to be forgotten, but to be shaped anew.

Sajid Bin Doza, PhD, is an art and architectural historian, heritage illustrator, and cultural cartoonist. He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Design (SoAD), BRAC University. He can be reached at sajid.bindoza@bracu.ac.bd.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments