The Culture of Intolerance and Resistance to Change - Part 3

The tragic events of August 1975 had cascading effects in our cultural life, with very few equals in our tumultuous history. It was to be the beginning of a long and debilitating experience as our political life i.e. a new nation with a nascent democracy, strong trends towards secularism and progressive efforts at driving culture, was fast morphing into autocracy. The many military coups and counter coups as well as Martial Laws, with the constitution being suspended saw the rise of a variety of dictators who went on to systematically cripple all achievements, expectations and aspirations of our hard fought liberation war.

Cultural activism nearly came to a halt as we grappled with how far our new usurpers of power would deride culture as we knew it, and introduce newer elements which were alien to most of us. For one, the easiest ruse was the divisive implant centering on our identity. Much efforts were expended to replace the inbuilt secular notion of Bengali culture and nationalism with a stridently communal version of 'Bangladeshi nationalism' - which sought to 'Islamize' the nation and once again bring in the cultural and political divide that precipitated the partition of India in 1947 and in no small measures, our liberation war of 1971.

However, it still wasn't time for culture to take the back seat of progress although it was obvious, it was neither in the driving seat. To be clear: 'national culture' envisaged by our new rulers was limited to the state run BTV and Bangladesh Betar and the mass media. A rigidly enforced 'vetting' process meant that each and every cultural component was under the scrutiny of the military. There was to be no mention of our Liberation War, the slogan 'Joy Bangla' was implicitly banned, television dramas and serials were under the spanner, and music was 'controlled' by elements expressing 'loyalty' to the military's scheme of things. Any content that even had a passing mention of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman or the Awami League was heavily censored. Similarly any cultural component which our rulers thought were 'Hindu' in nature was discouraged and taken off air. Much to our chagrin the hated collaborators of 1971 were also making a resounding comeback to political, cultural and national life.

The print media too had to tone down its language and various check and balances were in place to ensure no one deviated from the 'official line'. Advertisements were equally controlled and had to be cleared by hefty censorship before they could be aired. So severely was our culture challenged that for a while it seemed everything was lost. But that was not to be, for our military rulers realized the hard way, that their handful of carefully cultivated cohorts and cronies in 'nationalist intellectuals', artists, musicians and other 'cultural parasites ' were no match to contend with the growing resistance of the progressive democratic forces that dominated culture of pre-1975.

Another aspect to our culture post 1975 was business, and the military rulers knew for certain that our crafty cultural activists had mastered it efficiently as well as the art of creativity. They were thus a 'force' to reckon with, and to placate their feelings many military rulers would invite important artists and television personalities to the Presidential palace for 'frank exchange of views'. These meeting almost inevitably ended up with demands for media and creative freedom, end to censorship as well as representative democracy.

The inferences were embarrassing and unpalatable for our rulers – however they were nonetheless forced to capitulate to many demands. One positive note was the return of our current Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina from exile in India in 1981 that set into motion the demand and final restoration of democracy. It was yet a wait for many more difficult years.

While all of the above was happening there were few notable trends. Bangladesh Television started colored transmission in 1980 and with its vast network of relay stations that not only reached viewers across nooks and crannies of Bangladesh but secondary relays found a ready audience in our neighboring Indian State of West Bengal and Meghalaya. On the flip side, whenever political crisis hit Bangladesh plagued by strict censorship of news, people all across the nation would use improvised 'towers' made of large aluminum bowls and spittoons to catch grainy images of news of India's Doordarshan!

In very many ways the demands for access to information was getting stronger and broad sections of our cultural activists and intellectuals kept up the pressure through their consistent movements - whether they be in cultural activities fine-tuned with street agitations, humorous dramas, satires or musical soirees or intellectual confrontation in writings, fine arts and poems in defiance of bans and control.

A new militancy grew among cultural activists in all fronts to challenge each and every move that constricted our liberal space, and soon enough political parties were compelled into action based on the demands of the struggling young. The young were of the view that if autocracy was to be overthrown for good, they demanded that all cultural and political forces unite in one major push. A broad based movement in 1987-1988 nearly brought the nation to a standstill with multiparty hartals and agitations, but the dictator of the day used high handed measures as well as guile and tact to break up the unity. It would prove to be short lived.

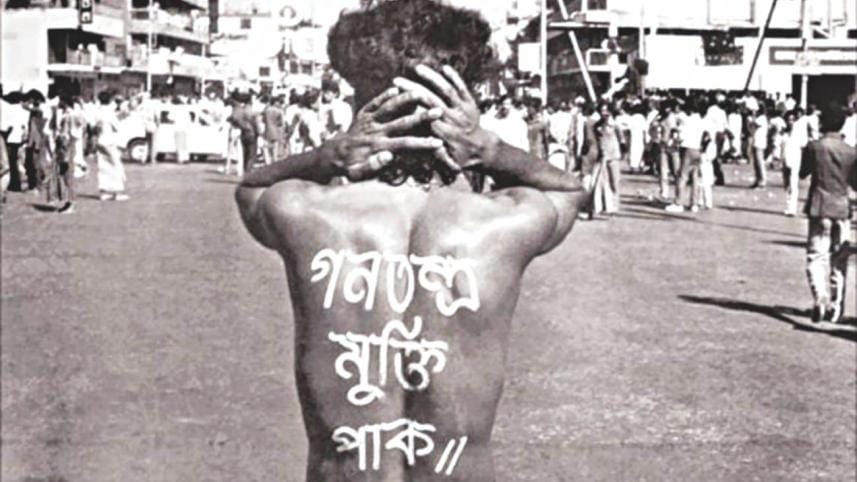

By winter of 1990 when the anti-autocracy movement commenced things were emotionally charged as well as tragic. The daily street agitations and hartals unnerved the dictator, and his storm troopers were deployed in great numbers to thwart the student led movement. It was precisely then that the pivotal turning point came about. The killing of Dr. Shamsul Alam Milon, Noor Hussain and Jihad led to angry and nonstop outburst of protest with Dhaka University students swearing over the dead body of Jihad never to return home until the autocrat was ousted.

And thus it was that the young students consisting of numbers from all political affiliations (including far right parties) united to form the Chattra Oikya Parishad. Much more blood was spilt onto the streets of Dhaka. The end came when students of DU fought day long battles in the Arts Building resulting in dozens of deaths. The resultant backlash meant the autocrat had no option left but to resign on the 10th of December 1990. This was perhaps the very first time the country witnessed such a show of unity and force, but it also happened because the mainstream political parties took a queue from the restive young students and together pushed out autocracy.

The scenes of jubilation in the streets of Dhaka post 10th December 1990 could only be compared with the historical 16th December 1971, with the only difference being: most of the young in the student led movement weren't even born at the time of our liberation. It was time once again for the young to deliver the nation out of the depravity of usurpers drunk with power. It was also the beginning of a torturous process to finally usher in democracy and restore our culture back to its original days of glory.

To be continued...

Maqsoodul Haque (Mac) is a columnist and a jazz-rock fusion musician

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments