From Triangle to Rana Plaza: Workers must be the priority

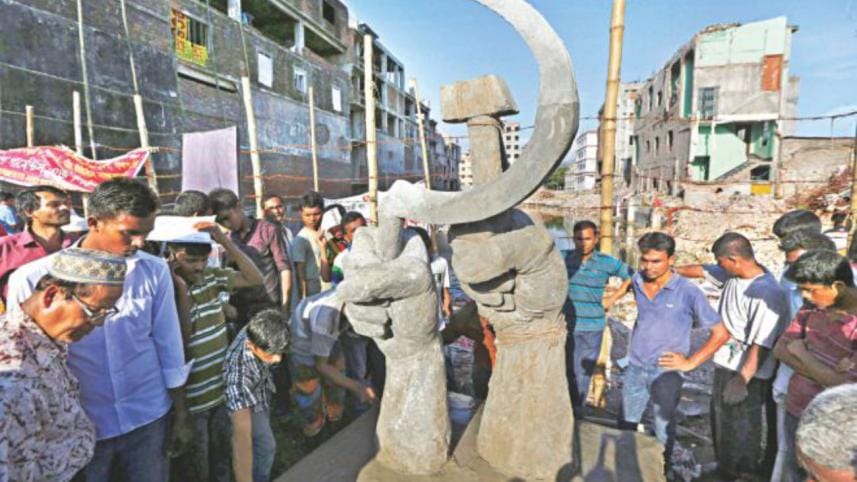

Over four million people's lives are closely intertwined with the ready-made garments (RMG) industry in Bangladesh—as are the deaths of over a thousand workers of Rana Plaza, which collapsed on this day six years ago. I remember it was a day of scorching sunshine. The Bengali New Year had begun only ten days earlier. This is usually a time of joy and celebration when people take a fresh look at their life and make plans that would change their future. What was it like for those ill-fated workers?

On April 24, 2013, their day began, like workers in 59 districts across the country, with the familiar drone of machines. The nine-storey Rana Plaza had five clothing factories located in different floors of the building. News of cracks in the building had reached the workers but they were told to come anyway, and there was nothing they could do about it. Everything, however, changed when generators on the top floor kicked in after a power outage and the whole structure imploded. In a matter of minutes, it came tumbling down, floor by floor, like a house of cards. The rest is history.

Most of those who died in the collapse were aged between 13 and 30, with 58 percent of them between 18 and 25, and they were paid somewhere around Tk 3,000 per month. These figures make you shudder, and you wonder if there could be a more meaningless death. Six years on, those whose greed and corruption led to these tragic deaths couldn't yet be brought to justice.

When we look at the circumstances surrounding the Rana Plaza collapse, we are reminded of another incident that took place over a hundred years ago: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. It happened in New York City, on March 25, 1911. Like the owners of the factories in Rana Plaza, the owners of this factory, located in the Asch Building which is currently part of New York University, also exploited its workers. Most of these workers were immigrants who came to the US from Italy and some Eastern European countries for a better future. They worked on a contractual basis, over 12 hours each day, and were paid a weekly wage of USD 7-12.

At that time, there was a movement going on which demanded increased wage, shorter working hours and better work environment for the workers. The movement, launched by the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), boasted about twenty thousand members spread in various factories, including the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. But the factory owners stubbornly pushed back against demands for reforms. It was against this backdrop that the fire incident took place, causing the deaths of 146 workers, 123 of them women and 23 men. Of the 146, 62 victims jumped to their deaths while the rest died from fire and smoke inhalation. The exits and stairwells of the building were locked from outside which made it impossible for many to escape from fire.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire had a huge impact on the labour movement in the US. It moved the legislators and common folk alike and provided the rallying cry for improved factory safety standards. In a demonstration organised by the labour unions ten days later, 80,000 people turned up to express their solidarity with the demands of the workers. Over 300,000 people joined a rally organised to pay tribute to the fire victims. Two years after the Triangle incident, the weekly working hours were reduced to 53. It also led to the formation of a Safety Code as well as 36 new laws on safety, factory inspection and other issues made within the first year of the incident.

The Rana Plaza collapse and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire have several things in common. The victims in both cases had to endure hardship and exploitation as part of their daily lives. Both incidents were set in backgrounds hostile to the interests of workers. The Rana Plaza disaster seems like a replay of the Triangle tragedy, some hundred years apart, and both triggered universal calls for change in how workers are treated. In our case, however, the pace of change has been frustrating. The labour movement in Bangladesh couldn't yet gather enough momentum as workers have to face a myriad of threats including arrests, attacks and lawsuits if they try to speak up about the need for decent wage, workplace safety or job security. There is a climate of fear across the factories. This is really unfortunate because a stronger labour movement and a motivated workforce actually helps in the production process which can contribute to better outputs.

After Rana Plaza, several cases were filed, and in only two of them, charge sheets were submitted to the court. Police have filed a murder case in which 41 people were made accused. Of them, 32 are out on bail, two deceased, and six are absconding; only Sohel Rana (who owned Rana Plaza) is in jail. The excruciatingly slow process of trial, while a judicial issue, doesn't at all help the grievances long nursed by workers about the continued disregard for their rights. If anything, it further aggravates them. Who will they turn to for their problems? In the last six years, there has been no substantial development in the RMG industry that could make the whole supply chain responsible for the change that is being desired.

The BGMEA is moving ahead with a vision: turn the industry into a USD-50-billion one by 2021, when the country celebrates its golden jubilee. It's an ambitious goal, and it will be a big achievement if we can fulfil that goal, but what about the workers? Can an industry expect sustainable growth without a properly motivated workforce? Can the image of the industry or the country remain untarnished if the voices of its workers are silenced and their rights denied? History has shown that only a proper labour movement can bring real change in the industry.

Taslima Akhter is President, Garment Sramik Sanghati, and a photographer. The article was translated from Bangla by Badiuzzaman Bay.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments