Bangladesh can avoid the middle-income trap yet

The World Bank is not only a place for economists and statisticians, but also an abode of poets who often coin some literary or figurative terms that rule the domain of policymaking jargon. In the early 1990s, they phrased a term called "the East Asian Miracle," which was later demystified by numerous economists as a planned journey of East Asia to develop its human capital.

The phrase "the middle-income trap," also coined by the World Bank, has been used as a powerful weapon to scare some growth-generating countries, so they remain vigilant in navigating their journey to become developed countries. While the organisation's intention is not vicious, the way they describe this trap is theoretically flawed and more of a cliché. Growth means a percentage change in GDP, which is composed of a million factors that can never be strangled or trapped altogether by any mechanism or magic.

Axel van Trotsenburg, World Bank's managing director of operations, during a visit to Bangladesh for an event to mark 50 years of partnership, warned that the country should be careful about falling into the middle-income trap. He asserted that the middle-income status is a hard struggle and it is a difficult task to go to the higher-income status. He cited the cases of Argentina and Greece, and mentioned that some Latin American countries went the reverse direction after reaching the middle-income status. He advised Bangladesh to follow the steps of countries like South Korea and Singapore, who graduated to being developed nations quite steadily without faltering.

The doctor who leaves alert messages for their patients is regarded as a well-wisher, since they are conscientiously caring for their patients' well-being. In that sense, the alert is well-taken. But the message is grounded in a conceptual phantasmagoria.

In 1956, economist Richard Nelson contributed to a concept – a theory of the low-level equilibrium trap. It says that a low level of income is a kind of a trap because it satisfies only the subsistence level of living where both the rates of saving and investment are terribly low. A little improvement in income will contribute to higher population growth, which will in turn push the per capita income back to its low level again, and hence it is an inescapable situation – a trap.

But that is not the case for the middle-income countries whose past is the story of good savings, handsome investment, and fairly controlled population growth. Poor countries with feeble growth rates (say, below three or four percent) cannot dream of becoming middle-income countries. The countries that graduated to the middle-income status were able to generate more than five percent growth before graduation. Hence, assuming a trap or a cul-de-sac in the middle-income bracket is theoretically flawed.

Then why do some policymakers talk about the trap? Simply because it feels like so. But the fact lies in the very nature of the marathon towards becoming a middle-income nation. The journey is too long, and many nations fail to uphold the growth momentum by upgrading its institutions and governance.

According to the World Bank's latest classification of countries, a country exceeding per capita income of USD 1,085 is marked as a lower-middle-income country. Bangladesh, with its per capita income of USD 2,824 (FY22) – as per the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics – falls in this category. If a country can exceed the per capita income of USD 4,255, it will be regarded as an upper-middle-income country. To be regarded as an upper-income country or a developed nation, the per capita income must exceed USD 13,205.

It is obvious that this classification portrays the marathon for a middle-income country not only as the longest one, but also as the most critical navigation over the classification spectrum, making some people think of it as a trap. But it is just a number game that requires plenty of patience and planning – just like playing chess quite diligently and intelligently to win the game. Mathematically, a country that has just graduated from a low-income status to a lower middle-income rank must increase its per capita income almost 13 times higher than its current level, requiring 53 years if the country grows at a steady rate of five percent, and 44 years if the growth rate is steadily six percent – which is quite challenging.

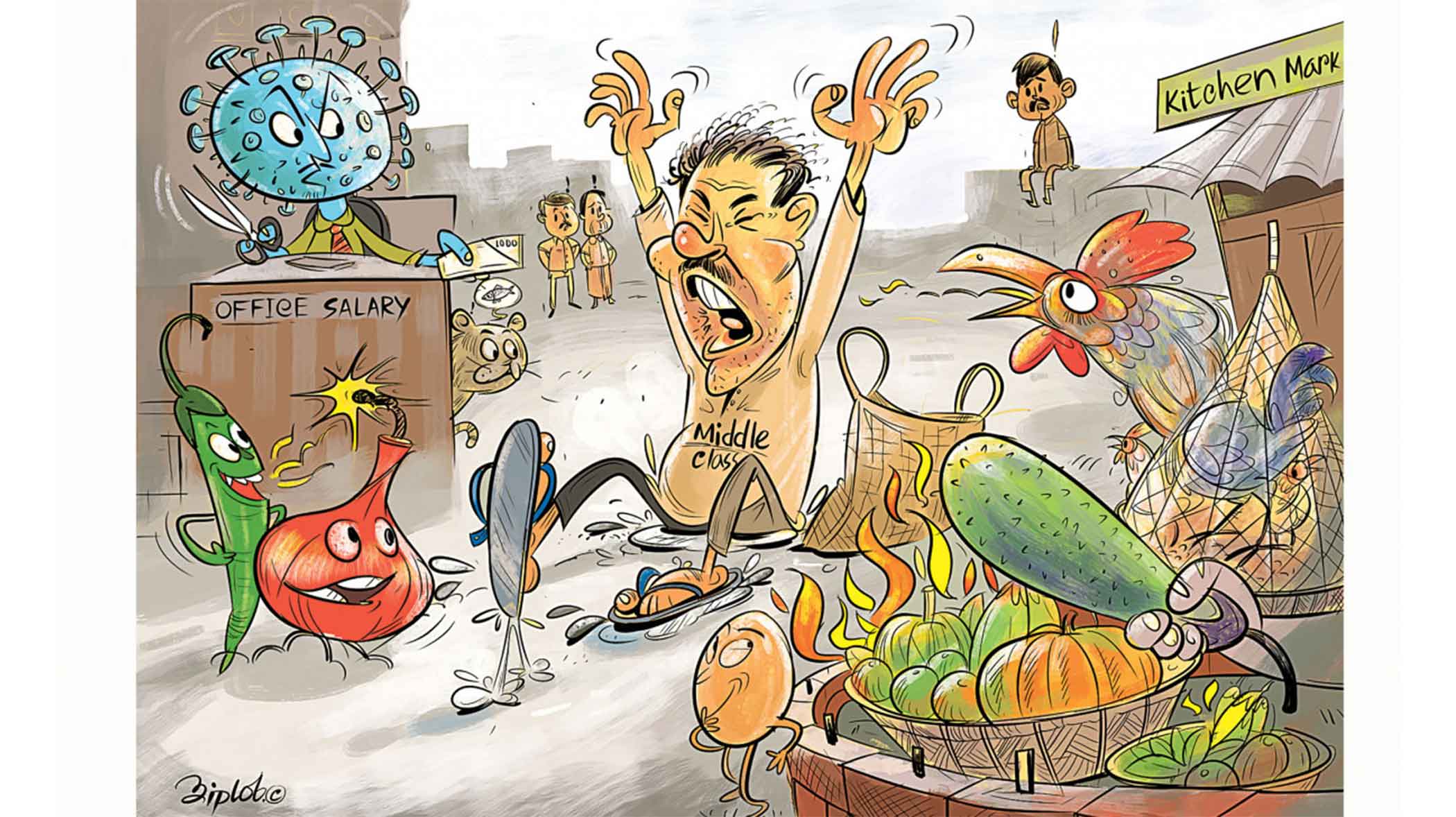

Practically, a country's journey over half a century is supposed to confront global recessions, crises, pandemics, wars, and climate shocks – when growth rates may fall or look poor. On top of global factors, the country itself may fail to develop decent institutions that are at the root of shepherding a country into a fully-fledged developed nation. This was the case for both Singapore and Korea, who succeeded in strengthening the basic three institutions: education, health, and finance. And if Bangladesh's journey takes too long in the middle-income episode, the reasons will surely be anchored in the poor institutional performance of these three areas.

If Bangladesh's budget allocation for education and health remains as low as it is now, it will justify the illusion of the trap, and will make the journey tardier and staggered at times. Its finance is increasingly turning into a hostage at the hands of loan defaulters, money launderers, and politically empowered bank looters. These three institutions together, if not correctly addressed, will make the journey to becoming a developed nation feel like a trapped expedition for Bangladesh.

Even if the country grows steadily at six percent, it will take another 26 years to achieve USD 13,205 in per capita income – the lowest rung for a developed nation. The probable date thus seems to be somewhere near 2050. Better late than never. Bangladesh experienced a silver lining in growth performance that displayed a pattern of acceleration until the pandemic torpedoed global growth. Bangladesh's growth volatility is one of the lowest in the region, suggesting that its growth will not fluctuate like Argentina's or Greece's.

Bangladesh's economic leadership must devote its integrity to ensuring quality growth along with lower income inequality. But its institutions must be knowledge-based, rather than being obedience-based. Its pending reforms must be initiated by individual institutions once they are allowed to exercise their autonomy, guided by the best global practices of learning and research. If so, Bangladesh shall never succumb to the so-called ghost stories of the middle-income trap.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland in the US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments