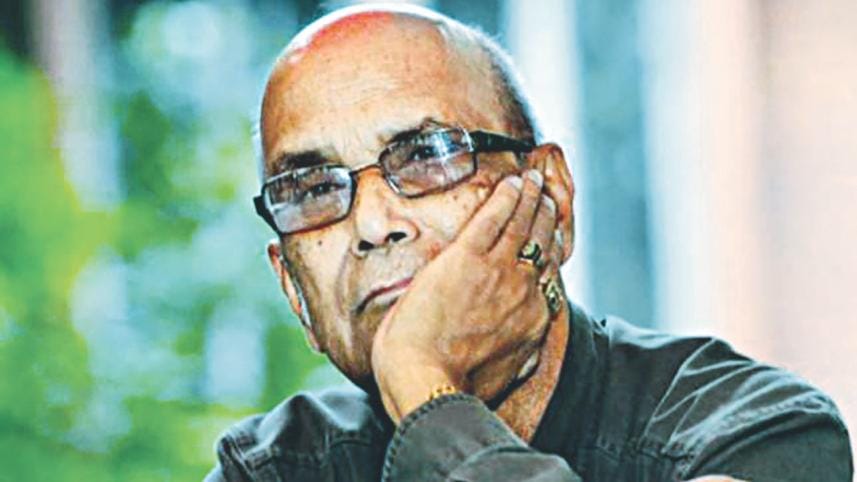

A magician with words

Every time I heard him speak I felt dazzled—dazzled by his thoughts, his insights, his ability to pinpoint what needed to be understood, his precision of language and his immaculate choice of words in expressing himself. Each time I heard him I felt what a magician with words he was.

Syed Shamsul Haq's presence in Bangla literature is so all-encompassing and his brilliance so overwhelming in all the branches of creative writing in which he is present that the accolade that he was a literary genius would not in any way overstate his extraordinary talent.

Syed Haq, as he was called by most of his admirers, is simultaneously a novelist, a poet, a playwright, an essayist and a powerful social commentator, and in all these varied fields he impressed his readers with his originality. In everything he wrote he showed his uniqueness just as much in what he had to say as in the way he said it. He had an intuitive sense of the format that would best express his thoughts—whether through a poem, a play or a novel, etc.

"Before him most of the well-known novelists or short story writers based their stories on rural Bengal. But Syed Haq captured the life of urban Bengalis and wrote about the turmoil, tensions and contradictions of the rising middle class," wrote Professor Anisuzzaman pointing out the new trend in literary work that Syed Haq's writing triggered and how a whole new generation of writers was created under his influence.

In all his works his vigour and zest for life were prominently present which he expressed in ways that only his writings could. Every moment was for him a new, never-again-to-be-lived moment and which deserved to be experienced in everyone's unique ways. But as he never missed a chance to state that one must have the courage to "want to experience it."

On the occasion of his 83rd birth anniversary he commented that birthdays are not of any significance and neither is age, "only life is, and that should never escape our mind." He urged everyone to be conscious of the beauty of life and see this beauty both in its serenity as well as in its turmoil. For him life itself was an inspiration as he said in an interview that "life has to be driven, for which you need strength." By suggesting life to be "driven" he probably meant that life must signify movement, and that movement must be guided by individual dreams. To pursue dreams there has to be ambition to make that dream come true. Nothing happens by itself, it has to be "asked for," there has to be an inner urge to "want" it. As for the "strength" one needs to drive life, he probably was referring to the "strength of character" that is innate in all of us—waiting to be recognised and nurtured into life every moment that we are alive.

A writer's tool is language and of course words are at its heart. Here was a special talent of Syed Haq—his choice of words. In all his writings the words that he used always seemed like the only words that could have been used in that particular situation, be that in describing a scene, an emotion, or an event. I always marvelled at his choice of words and never stopped wondering how he could manage to think of the most appropriate word at just the right time. The more I read him the more I realised both the beauty and importance of words for effective writing. I owe him my own greater attraction and love for words and how to value them in both personal and professional life.

In my view his exceptional strength lay in kabya nattya, lyrical plays (plays written in rhymes), the two most famous ones being Payer Awaj Pawa Jai (1976) written in the background of our liberation war, and Nuruldiner Sara Jibon (1982), a play based on the peasant uprising in Rangpur area during the British colonial period. In both these plays he truly excelled himself and majestically so. The power of the sentences he wove into mesmerising long monologues was magical. The dialogues that pitted the powerful characters he created swayed his audience from one point of view to another as the battle of words kept his listeners glued to each word as if to miss one would amount to missing the whole plot.

Nuruldin also showed the capacity of a writer to take a forgotten hero of history and bring him back to life and to public consciousness with meaning for the contemporary world. This he did with incredible power and impact.

But just as powerful the stories, so was his narrative capacity. He captured the intense drama, the deep emotions and the highs and lows in individual lives in endless verses. It was amazing how he was able to tell highly complex stories and narrate history-making events in verses that never seemed for a moment to be laboured, they flowed naturally. It was equally amazing how he was able to capture the imagination of his audience and keep them mesmerised throughout the hours that staging his plays required.

One needs to make a particular mention of his two translations of Shakespeare's Macbeth and The Tempest that he did in the late sixties. About translating great literary works into Bangla he said, "When you are translating into a language it has to be like the language in which it's being translated, with all its specialties and nuances. The translation will have to be a work in Bangla regardless of what the original language was."

His adaptation of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar into Gononayok was a remarkable piece of work with the power, the universal message and timeless appeal of the original play mostly remaining intact.

As a journalist I was intrigued by his comment that he thought novel-writing was to him "creative journalism". While trying to understand what he meant I discovered anew the art of novel-writing and the importance of journalism: Both try to depict the realities of life but while the latter does it through daily reporting and commenting, the former depicts the same through creatively weaving the same reality into a composite story with a far deeper meaning that perhaps gets lost in the cacophony of the daily dose of the media.

Syed Haq's remark jolted me into looking at my own profession and to try to find a bit more meaning and substance in what I was doing.

He was a patron of The Daily Star drawn to the paper from its inception due to his friendship with SM Ali, the paper's founding editor. He was a constant inspiration to me for what we were doing. He would call me on most occasions when he liked a report, a feature or something that I wrote. He seemed to rejoice at the fact that English journalism was acquiring a new maturity in the newspaper of his choice and wanted to encourage us every step of the way.

On a personal level I would like to flatter myself with the thought that I enjoyed a special affection from him which he would generously express every time he would see me. He was particularly effusive when my elder daughter, Tahmima Anam, made her debut as a novelist and I remember him saying at the launch of A Golden Age that, "There is a first novel in everyone's heart. The real challenge will be for you to write your second one." Several years later he told me after reading Tahmima's The Good Muslim that he was very proud of her as a writer. He would chide me for not ever trying to follow my father, Abul Mansur Ahmad, in literary writings and was particularly happy that she had taken after her grandfather.

Syed Shamsul Haq was one of the most brilliant literary figures of our time. His short stories, poems, novels, children's novels and lyrical plays make him the most versatile and accomplished writer of independent Bangladesh and perhaps the greatest literary figure in Bangla literature in the contemporary period.

Mahfuz Anam is Editor and Publisher, The Daily Star.

This article was originally published on September 27, 2017 in a commemorative book titled Syed Shamsul Haq Swarangrantha on the celebrated poet and writer.

Comments