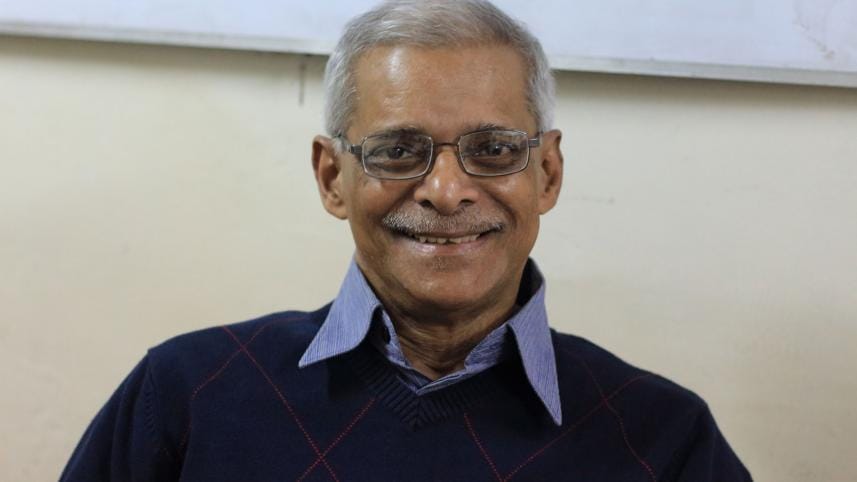

Freedom fighter Tariq Ali: A man of great heart

With the sad demise of Ziauddin Tariq Ali, a colourful personality of the generation of Muktijoddha, a life-long crusader of secular liberal nationalist values of the liberation struggle has left the arena of history. The loss is difficult to describe because he not only belonged to an epic chapter of the Liberation War, but tried to make the past relevant to our present in order to build a better future for all. He was a life long Muktijoddha in the true sense of the word, who dedicated himself to keep the flame of freedom burning.

Tariq Ali was a passionate person, apparently a man with contradictory identities. He was a chemical engineer by profession, who worked at home and abroad in running and constructing sophisticated pharmaceutical plants. As an engineer, he had to be engaged with pure science, technology and reason, but as a person, Tariq Ali was passionate and highly emotional, not for himself, but in relation to the Bengaliness at the core of the struggle for liberation.

He was an engineer devoted to music; songs were his means to expressing himself and communicating with others. It was through music that Tariq Ali embraced and upheld the cultural richness of Bengal. While studying engineering in Lahore, he created an island for himself and his friends where they continued to defy all odds and celebrated their cultural identity. His friend circle during those days in Lahore included Mohiuddin Ahmed of University Press Ltd., Engineer Mosharraf Hossain of Chittagong (ex-minister and AL leader) and a few of the young CSP's undergoing training or serving at the central ministry. On his return to Dhaka, Tariq Ali joined his profession but more so the bandwagon of musical culture, as a disciple of Waheedul Haque and friend of Mahmudul Huq (Benu Bhai to others). Those were the days of the cultural upsurge of the Bengali nation and Tariq Ali was part of that journey, a humble participant in the musical circles, but a passionate and committed one.

In 1971, when the nation jumped into the Liberation War, Tariq Ali did not hesitate to leave his job and join the struggle. How he was united with the musical band in Kolkata and the Mukti-Sangrami Shilpi Sanstha was powerfully depicted in Muktir Gaan, recorded then and later lost by Lear Levine, which was then rediscovered and recreated by the young film enthusiast duo Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud. Muktir Gaan brought back memories of 1971 to the new generation, which earned more significance in the backdrop of the denial and distortion of history since the brutal murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Muktir Gaan, along with few other glaring example of memorialisation, like Ekattorer Dinguli by Jahanara Imam, electrified the country's young minds and created a bond with their pasts.

Tariq Ali, the central figure in the documented history of Muktir Gaan, came into the limelight as a result but as always, he made no claims to fame and meticulously avoided occasions of formal celebration or media exposure. He was a witness to history and learned his lessons of life from the experience of moving around the refugee camps and encountering the peasant guerrillas of the Liberation army. People's distress and the people's army became a part of his experiences from 1971 and he carried an intense respect for them.

I remember the deep understanding Tariq Ali developed with Julian Francis, an aid organiser during 1971 and now an honorary citizen of Bangladesh, a person still haunted by the tragedies he witnessed in the refugee camps. Julian had kept his painful memories hidden and had not spoken or written about them for long, until he met Tariq Ali and visited the Liberation War Museum in 2007. They established a rapport of their own. Julian Francis noted in an obituary that Tariq Ali phoned him two months before he passed away to inquire about his health during the pandemic and to encourage him once again to write down his memoirs. Tariq Ali was known for his wit as well—he once told Julian, "We are both connected to two wars, the Bangladesh Liberation War and because both of us were born in early 1945, Hitler realised that he had no hope as far as the Second World War was concerned."

Recalling this conversation, I wonder about another connection Tariq Ali had with the Second World War when the people's cultural movement flourished in Bengal with the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), uniting talented young artists to launch a great musical movement of resistance to fascist forces. IPTA belonged to the golden era of protest songs, with their office at 44 Dharmatala Street in Kolkata. In 1971, the same place became the office of Muktisangrami Shilpi Sangstha to conduct their rehearsals and plan their work.

When in 1996, we the eight friends embarked on the journey to establish the Liberation War Museum, Tariq Ali found a new lease of life. Saying adieu to his career abroad, he returned to his homeland not to look for another career but a meaningful existence. Gradually, Tariq Ali redefined himself, not an easy task at that age. He became a man of the museum, especially since the construction of the new museum at Agargaon began in 2011. The engineer in Tariq Ali took up the challenge of building the museum with state of the art technical facilities. Architect Rabiul Hussain, another trustee, supervised the design and its implementation and both of them were ably supported by a team of architects, civil engineers, structural experts etc. It was a landmark event in the nation's history, where the support of people from all walks of life helped the new museum to be constructed successfully.

Meanwhile Tariq Ali, as a civil activist, became more and more committed to protecting the rights of minorities, both religious and ethnic. The rise of fundamentalism and communal discord pained him deeply. He considered such cases to be the destruction of the core values of our Liberation War.

Tariq Ali, as a founder trustee of the Liberation War Museum, felt comfortable to remain on the sidelines. He was always reluctant to be on the centre stage. He found great solace when members of the new generation were engaged with the episodes of history and evidences of the past. He was a passionate person, emotional about everything related to the Liberation War, and tears would roll down from his eyes whenever he witnessed a positive act or any small gesture eulogising the glory of the nation. He was driven by his heart, and his sincerity of purpose touched the hearts of many. He was not a man of the podium but he conveyed his message to people around him in the most heartfelt way.

While reading the condolences that poured in after his demise, one gets an understanding of how he touched other people as he was touched by them. Our good friend Barbara Thimm, a German museologist working in Cambodia, wrote to us, "When I received the message that Tariq died, my tears were running spontaneously. I am still feeling very sad. Feeling with all of you a great, great great loss… I only had the chance to meet him twice, but he impressed me a lot, the way he was. Strongly committed. And I got the impression, that he was a very good observer, commenting on what he saw with a twinkle in his eyes. I will keep this in my mind and heart."

Tariq Ali was driven more by the heart than reason. He reminds me of what French philosopher and mathematician Pascal said, "The heart has a reason, but the problem is reason does not know that." To understand Tariq Ali, one has to know the reason buried deep in his heart.

Mofidul Hoque is a war crimes researcher and trustee of the Liberation War Museum.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments