The Impeachment Blues

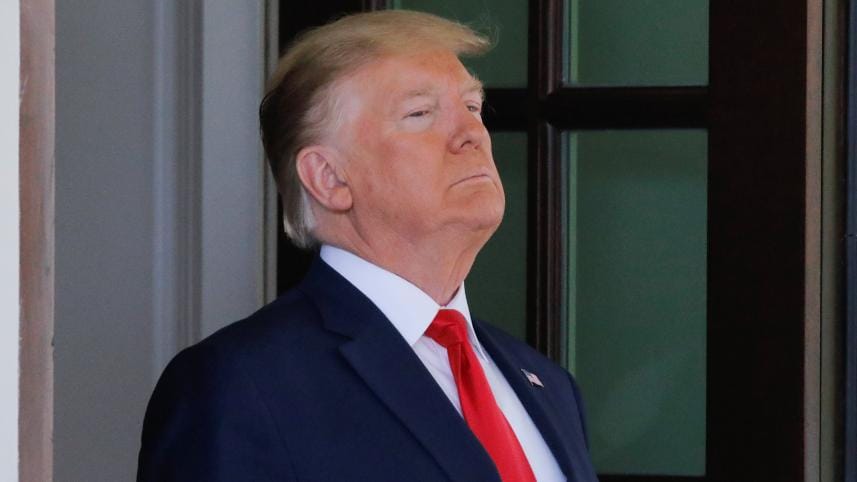

The most dismaying thing about the impeachment proceedings against US President Donald Trump is that they are falling so short of the constitutional gravamen of the issue. True, some Democrats in the House of Representatives, particularly Adam Schiff of California, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, do appear to understand the seriousness of the question before them. But most Republicans—egged on by Trump, who often complains that they are not doing enough for him—are on a search-and-destroy mission. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who had long been reluctant to proceed with impeachment, lost control of her caucus over the issue this summer and has ended up where she feared: in a bitter partisan fight.

At the risk of setting an unfortunate precedent by allowing Trump's numerous other abuses of power to go unpunished, Pelosi has narrowed the impeachment inquiry to presidential activity for which there is adequate proof, and that she and her Democratic allies think the American public can easily understand. That means Trump and his allies have a very limited target to shoot at.

The inquiry is thus focused on the fact that Trump withheld USD 391 million in congressionally mandated military aid to Ukraine and held out the prospect of a White House meeting greatly desired by that country's new president, Volodymyr Zelensky, while he and his accomplices pressed for political favours to help in the 2020 US election. In particular, they wanted Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden's son Hunter, who unwisely accepted a lucrative seat on the board of a Ukrainian gas company at a time when his father was in charge of Ukraine policy. (Both Bidens have denied wrongdoing and, thus far, none has been found.)

Although Democrats of course have strong feelings about Trump, they have lately tried to adopt a solemn tone. When Pelosi announced the impeachment inquiry in September, for example, she handed over leadership on the issue to the steady, tough-minded Schiff, removing it from the more openly partisan House Judiciary Committee, which has a weaker chairman (Jerrold Nadler of New York).

Hard as it may be to believe, the period since then has been one of relative calm, in which the Intelligence Committee gathered closed-door testimony. That will change when public impeachment hearings begin this week. To make sure that their side is sufficiently tough toward witnesses, Republican leaders have added the rambunctious Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio to the Intelligence Committee.

The closed hearings—not unusual in investigative matters, and unlike in the cases of Presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, there's now no special prosecutor to do their research—produced a strong case against Trump. That was partly because the format was more productive: committee members don't gain by preening and being disruptive when no cameras are present. But the most important factor—one without modern precedent—was the courageous willingness of a number of fairly high-level, non-partisan government employees, most of them career foreign-service officers, to disobey White House orders not to appear. They risked their careers by going before the committee. Some quit their jobs to be able to do so; another has been removed from the staff of the National Security Council.

Trump, who understands almost nothing about governing, made a major mistake in attacking career public officials from the outset of his presidency. He underestimated, or just couldn't fathom, the honour of people who could earn more in the private sector but believe in public service. And he made matters worse for himself as well as for the government by creating a shadow group—headed by the strangely out-of-control Rudy Giuliani, once a much-admired mayor of New York City, and now a freelance troublemaker serving as Trump's personal attorney—to impose the president's Ukraine policy over that of "the bureaucrats."

Such unbounded "off-the-books" operations—whether Nixon's "White House Plumbers" or the Iran-Contra scandal during Ronald Reagan's administration—usually come to grief. I covered Nixon's impeachment, and although Trump is theoretically guilty of more serious offenses, there's one striking similarity: both men got in the deepest trouble for failing to recognise limits on seeking revenge against political opponents.

The sudden firing in May of Marie Yovanovitch, a longtime foreign-service officer and highly respected US ambassador to Ukraine who had tried to block Giuliani's political meddling (she was ordered, without explanation, to take the next plane out), greatly upset the already demoralised State Department bureaucracy. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, whose ill-disguised political ambitions have led him to remain close to Trump, simply refused to protect her.

Congressional Republicans could see from the memorandum on Trump's infamous July 25 phone call with Zelensky that Trump had pressured his Ukrainian counterpart to take actions that would benefit him politically. Many also know that withholding congressionally approved aid to Ukraine likely constitutes an abuse of power, an impeachable offense. But, desperate to protect the president, Republicans have careened from one frustrated defence to another.

As a diversion, they've tried to smear and even expose the whistleblower whose report triggered the impeachment inquiry. For example, Trump recently shouted to the press corps assembled on the White House driveway that the whistleblower's charges were all "lies," even though the charges have been broadly confirmed by witnesses before the committees. Exposing the whistleblower's name—which Donald Trump, Jr, among others, has tried to do—could be a federal offense (except if done by the president), and could put that person's life in danger.

Although some cracks have appeared in the Republican front, Trump seems to be maintaining his grip on the party for now. He insists that the Republicans would have lost the 2016 presidential election if not for him, and that he therefore is owed their fealty. For good measure, he's offered help to Republican senators—particularly Majority Leader Mitch McConnell—who are seeking re-election in 2020 (a loss of four Republican seats would lead to the Democrats taking control). Some major fundraising events are, of course, to be held at the Trump International Hotel in Washington, DC. At least one ethics expert says that Trump's contributions to senators before the impeachment vote could constitute a "bribe" (yet another impeachable offense).

Trump is becoming more confident in his own instincts, and now has almost no aides who will challenge his ideas. At the same time, he's increasingly agitated about his likely impeachment in the House. As a result, the president is even more impulsive in his conduct of foreign policy, in particular regarding the calamity in Syria.

Almost all American presidents have honoured their constitutional duty to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed." But Trump, with his l'état, c'est moi approach, views his role very differently. As a result, he is in the greatest trouble of his presidency so far.

Elizabeth Drew is a Washington-based journalist and the author, most recently, of Washington Journal: Reporting Watergate and Richard Nixon's Downfall.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments