Why does the emperor have no clothes?

America has had a fairly inscrutable history. Haven to the oppressed in the European continent, its early settlers, while relishing the fruits of freedom, pretty much exterminated its indigenous inhabitants. At the same time, as a reaction to absolutist monarchies elsewhere in the world it created pluralist institutions. In this "New World" the Lord did not supposedly anoint Kings investing them divine rights, but imparted them directly to the people through the Constitution. While their leaders penned and pronounced praises to liberty (in the "Federalist Papers" written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay, for instance), notions of equality were not extended to their black African slaves. While they were explicit in expressions of their new world coming to the aid of the old, their entry into the Great Wars of the twentieth century was actually effected only when their interests were directly threatened. They initiated the use of nuclear weapons of mass destruction in warfare, only to champion their elimination when others, particularly not of their ilk, sought to acquire them. While their intelligence agents relentlessly worked towards regime-changes in other countries, they themselves reacted adversely when others allegedly sought to do the same in theirs. So, how was it that America, such a bundle of contradictions, able to project itself as a beacon of morality on the international scene over such a sustained period of time?

The answer perhaps lies in what Americans have always excelled in: effective marketing. About 1775-76, Thomas Paine had published the "Common Sense". The historian Gordon Wood saw it as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era". It marshalled the arguments for the fight for liberty of the 13 American colonies against the British. The fact that the American Revolution almost coincided with the French counterpart helped. Indeed the French political scientist Viscount de Tocqueville in his two works, Democracy in America (in the 1830s) and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856) extolled American values. He viewed them as a healthy relationship between the market and the State. Soon America was being projected as the "City on the Shining Hill", with a "manifest destiny" to expand territorially and ideologically. Eventually a political culture evolved that stressed America's "exceptionalism".

Doubtless American support to allies helped defeat German Nazism and Japanese imperial might. The establishment of the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions on American soil aided the perception of America as the leader of the "free-world". It saw itself charged with the responsibility of "containment", a term coined by the diplomat George Kennan, of Soviet expansionism and Communism. When Karl Marx's theories were turned on its head and instead of "capitalism" it was "communism" that collapsed due to its inner contradictions, America emerged as the unchallenged superpower. With it came a sense of hubris. Its ultimate evidence was the 2003 invasion of Iraq under President George Bush. President Bush understandably made no claims to higher enlightenment. However, his administration was moved by some who did. They were the Neo-conservatives or the "neo-cons", people like Paul Wolfowitz, Charles Krauthammer, and Doughlas Feith. They were disciples of Professor Leo Strauss, the German-American thinker who was deeply influenced by the Classical Greek philosopher, Plato.

Plato believed that it is only a handful of individuals, who truly understood the essence of what is great and good. He called them "Philosopher Kings". He lauded "empiricism" over "abstraction" and "shadow-learning". This was characterised perhaps the world's most famous apologue in philosophy, in his "allegory of the cave". It is not just that new ideas have ancient roots. All "true history" is really "contemporary" as Benedetto Croce observed. Alas, ancient sources are also often distorted to justify current unsavoury acts. Even if the neo-cons were pushing their interpretation of Platonism, they were in contrast to the founding fathers who derived inspiration from the study of Constitutions by Plato's student, Aristotle. And for the record, Aristotle had famously said "Amicus Plato sedmagisamicaveritas" "dear is Plato but dearer still is the truth"!

Fast forward to the present. The supposed leadership role of America came with a heavy price. America was made to play the very role that traditionally the founding fathers had been chary of: searching for monsters to destroy abroad. While they won the Cold War because of the implosion within the adversary camp, they either drew or lost many fights like Korea or Vietnam, or became mired in an unending conflict like Afghanistan. They were the strongest power in the world. But situation that meant little because their power derived from weapons that they could never use. Sometimes unfairly to the Americans, others fuelled their ego of leadership of the free world, in the words of the current President Donald Trump, ripped them off in trade and commerce! Newer powers were emerging. Some had acquired the dreaded nuclear-weapon retaliatory capacity. China was rising. Not just militarily, but also economically. In the contemporary digital world, it was catching up with America in Artificial Intelligence. It had the capacity to feed the machine more mass-data, and algorithms to improve products and services and invent new ones. A "Thucydides Syndrome" was in the making. The sage of that name had observed that when Athens grew strong there was great fear in Sparta. History is replete with rising powers challenging established ones.

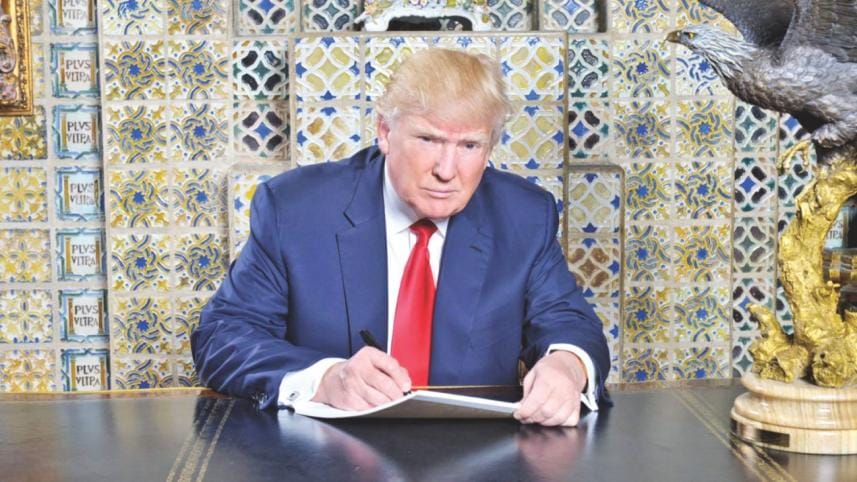

Trump is the product of exhausted America. He represents the viewpoint that the so-called leadership role with its high-price tag is not worthwhile. To him, the United States should be like any other nation that should act only in pursuance of its narrow self-interest. Recently at the United Nations, he rejected globalism and embraced patriotism. Many, like the Europeans, may think patriotism delinked from multilateralism could lead to nationalism. In Europe in the past it has in turn resulted in war. But Trump thinks differently. And right now he is the President. This thinking may be in many ways germane to contemporary American ethos. Some may argue that the idea of an intellectual restraint to the proliferation of such predilections might be in order. So has the time come for the "containment" of America by others in an ironical reversal of history? Opinion will be divided .The Emperor, in this case represented by the power of America, may not be wearing the clothes as the pretentious monarch in the fairy tale, which the clever and deceitful tailor had claimed were too fine for the human eye to see, but it is only because now he has chosen not to.

Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury is a former foreign adviser to a caretaker government of Bangladesh and is currently Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.

Comments