The many milestones of the women’s movement

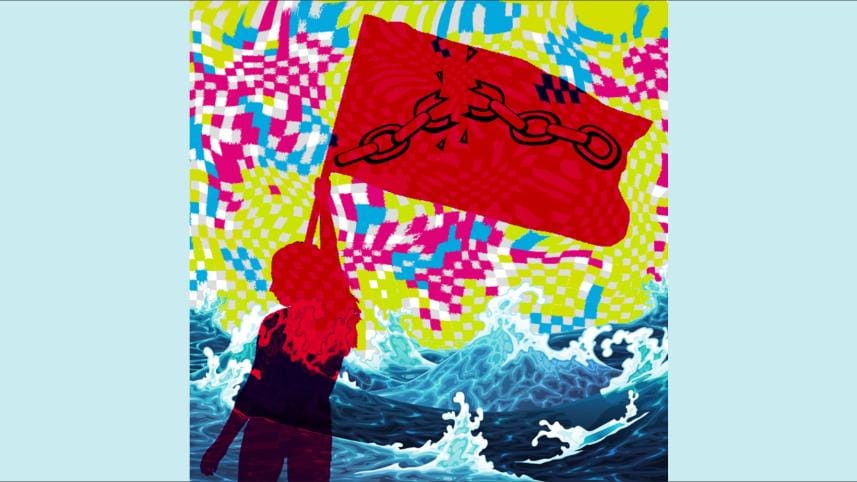

For the women's movement in Bangladesh, looking ahead can sometimes be a depressing task—the challenges and obstacles that we face are numerous, to say the least. However, when I look back at the last few decades, there also have been a number of milestones that we should be proud of, although there is always space to do better. This Women's Day, we should try and focus on a few of these positives.

Before the women's movement took off in Bangladesh, sexual harassment was not even recognised to be an issue, let alone the idea of a woman living her life in a dignified environment. Now, there has been a significant change in mindsets—the general population understands sexual harassment to be a real problem, and more importantly, women are able to come forward and speak out about sexual harassment, to the extent that in 2009, the High Court issued an 11-point directive on sexual harassment after a writ petition filed by the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers' Association (BNWLA). While there is still an appallingly high prevalence of violence against women, the women's movement has also been able to demand some dignity for abused women, and their pictures and names are no longer printed in newspapers or splashed across the headlines.

Another milestone achievement for us is the streamlining of women into the strategies and policies of development organisations. Gender issues now go hand-in-hand with development, and there is a gender perspective on every project. The development sector, specifically women's organisations, along with the government, have been able to create a society where there is female entrepreneurship from the grassroots level up to the top. If you just look at the number of bank accounts that have been opened by women over the last few decades, the developments in women's economic emancipation become obvious.

However, the most positive change that has come about is in the mindsets of people, and the society at large. Women are now able to speak out about violence and women's issues. Starting from the 70s, the voices of our activists have paved the way to laws, policies and action plans that put women at the centre, although implementation is still a struggle. This change is also reflected in the media. Once journalists would report on rural poverty, and all they would see were goats, houses, ponds—never the women! Now, the media is covering women's issues, and handling these stories sincerely and sensitively. The global #MeToo movement has even started a conversation around sexual harassment in the workplace in Bangladesh, and emboldened many women to speak out openly. This is a huge step forward because in the past, on the rare occasion when sexual harassment was addressed in the workplace, we used to keep the identities of perpetrators confidential and they could then move on and get a job elsewhere. If women have the confidence to name and shame, this will change.

There are other demands of the women's movement that once received a great deal of traction but have, unfortunately, not come to fruition yet. One of the most significant demands is the uniform family code that provides women, irrespective of religion, class, caste and ethnicity, with equal legal and social status and opportunities. The Bangladesh Mohila Parishad is still working on this issue and creating pressure for the removal of discrimination in the law in terms of gender, ethnicity and religion. This does not mean that no progress has been made. Only last year, the High Court ruled that the word "kumari" (virgin) cannot be used for the bride in the Muslim marriage deed, and it should be replaced with "unmarried". However, while Muslim marriage laws have been adapted to give women certain legal rights, the same has not been applied to women of other religions. The media needs to play a role here in putting focus on these disparities—it would be a positive step forward in building bridges between the different communities as well. The media has also focused on the economic emancipation of women, but it should be explored in more detail to express the contributions of ordinary women towards progress in Bangladesh—not just towards the economy, but also towards changing social and cultural institutions and creating spaces for women that did not exist before. We like to focus on the positives and achievements, as we should, but we also need to focus on their daily struggles against entrenched discrimination.

Going forward, one of the most important obstacles that we immediately need to deal with is in our law and justice system. We must review discriminatory laws with gender-sensitive eyes, especially with regard to inheritance and sexual violence. Another major field that needs to be focused on involves reproductive and sexual rights. It has been proven that sex education leads to less risky sexual behaviour. During my work, I have found that ordinary people are open to these discussions—even clerics and madrasa students—because these conversations are central to their lives, and are an important tool in reducing violence against women. Finally, we need to work on pension allowances for women aged 65 and above, to respect the sacrifices women make all their lives, especially in terms of unpaid care work despite daily obstructions, shaming, etc. The state tries in different ways to give dignity to women. This can be one of its areas of focus—an important one which can save them from being totally dependent in their old age.

In order to make the women's movement more sustainable in the future, we must acknowledge that there have been changes in how we protest over the last few decades. In the 90s, you didn't have to be a big organisation—anyone could stand up and protest. Now, the focus is more on the big names and VIPs, and less on the movements themselves. Every time there is a protest, there is a subtle competition on who turns up with the biggest banners and posters. This has created a class consciousness in the women's movement that wasn't there before, since those who have the most money will have the biggest banners. Our dependency on donor funding has definitely led to this state of events—donors want to see their branding on whatever they fund and need constant updates and reports, often with the pressure of a positive spin. This creates projects, not protests. On top of that, law enforcement authorities can also make it difficult for people to stand together, even if it is something as simple as a women's march. While all of us within the movement definitely need to look within and stop seeking the spotlight, the government also needs to understand that our protests are not anti-state, we are only against injustice.

When I was in Nepal in 2004, I was pleasantly surprised to see a huge women's march organised by the Nepali government, with the participation of key women's organisations. In 2008, the Bangladesh government also announced that it would celebrate March 8. I personally was happy to see this initiative, and I wanted to support the government to make the movement reach the grassroots. But within the women's movement, this created a divide that we are still struggling with. I understand the danger of having our movement co-opted by the state, but I believe that change must also come from within the system. It is now up to civil society, as the more forward-thinking and independent group, to support the state, monitor its activities and constructively critique the steps that are being taken. Change is possible if there is political will from the state, and civic society can lead the way by providing the utmost support.

Sheepa Hafiza is Executive Director of Ain O Salish Kendra. The article is the result of an interview taken by Shuprova Tasneem.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments