The Leave Trap

We mean to make things over,

We are tired of toil for naught;

With but bare enough to live upon,

And ne'er an hour for thought;

We want to feel the sunshine,

We want to smell the flowers;

We're sure that God has willed it,

And we mean to have eight hours;

We're summoning our forces, from shipyard, shop, and mill…

This song "Eight Hours", penned by IG Blanchard and composed by Reverend Jesse H Jones, gained popularity towards the end of the 19th century, eight years before the advent of May Day. They were both residents of Boston.

The song, which grieves for the miserable life of workers, and the freedom they yearn for, gave the workers' movement a new language. This song became a source of strength—a rallying cry. In all industrialised countries, including those in the Americas and Europe, workers gathered en masse to press home their demands for an eight-hour work day.

This song highlights how workers toiled for hours on end, forgoing their youth, their health, their lives and strength. They worked for 14 hours, 16 hours and even 18 hours. If they fell short by a few minutes, they were tortured. They were not given the chance to experience what it feels like to take a deep breath under the open sky, to be blinded by the sun's rays, or to feel its warmth on their skins.

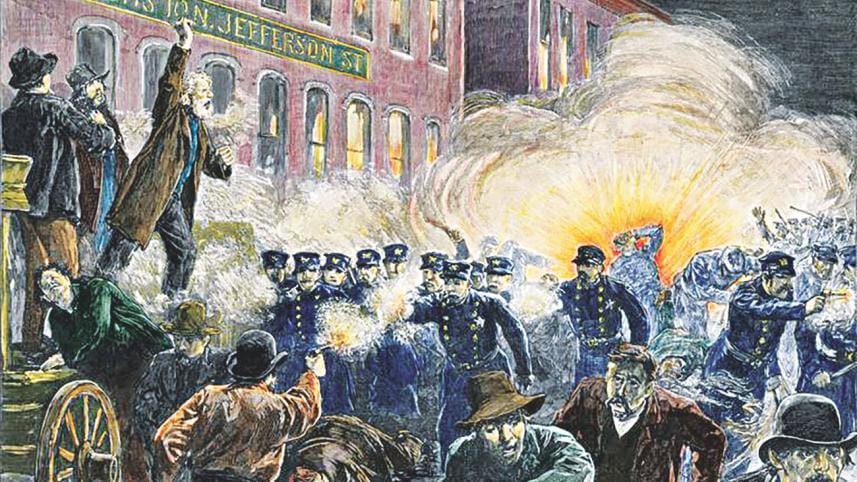

Instead, on May 1, workers in Chicago were shot, attacked, and hanged to death, for daring to protest and demand eight-hour workdays. Through their sacrifice, we were given the gift of May 1—and the issues related to labour rights, fair wages, and trade unions were brought to the forefront.

In the last 133 years, workers have achieved lawful recognition of eight-hour workdays and the right to take leave. One would think these are old demands, but how much has the situation of workers really changed in fast-industrialising countries like ours? Today, I want to talk specifically about the workers of the apparel sector. This industry is nearly 40 years old. Some would say, "In a fast developing country like ours, the workers get a minimum wage as high as Tk 8,000, and other benefits in addition. The situation of the workers is not what it used to be like."

Is this really true? We often discuss the broader issues of wages, workers' safety and trade unions. But to commemorate May Day, I would like to talk about a particular reality about the lives of workers that is often hidden from the public eye: the deception of standard work hours and the "leave trap".

It is true that the workday is legally recognised as constituting eight hours, but it is also true that workers are forced to work 11-12 hours, and even 14-16 hours daily. Every professional and physical labourer is entitled to get leave from work. According to the law, government employees get two days off every week. In some retail shops, private organisations and corporate houses, employees get a day and a half. Workers of the apparel and transport sector get one day off every week (52 days off in a year). Other than this, every year, they are entitled to 10 days of casual leave, 14 days of medical leave, 17 days of earned leave, festival leave totalling 11 days and maternity leave of 16 weeks. In total, they are given eight types of leaves. These leaves are necessary to preserve the physical health, mental well-being and productivity of the workers.

Then where is the gap? Let's delve into the topic with a few questions. Are the bodies of the government employee and the worker any different? Then why does one get less days off? Why do workers rarely get to claim the right to casual leave or sick leave? When do workers get the time to just relax and reflect?

Workers fall prey to a variety of illnesses and conditions associated with long work hours and malnutrition, but they cannot claim the 14 days of medical leave they are supposed to get. Just as often, they are unable to claim the 10 days of casual leave they are entitled to. Workers in many factories are deprived of the entire attendance bonus for the month, if they use even a day of casual leave. As a result, workers unknowingly forego their casual leave which is their right, for the Tk 400-600 attendance bonus.

If we look at the other leaves allocated to Bangladesh's apparel workers, it will help us understand even better just how the system deceives the workers. It will help us realise whether the lifeline of the Bangladeshi economy, and the main lifeforce behind our export earnings, ever get to see the light of day, or breathe the fresh outdoors. We can get to know why the gleaming dusky bodies of our workers are turning pale. Because there are shocking deceptions even in the system of weekly holidays and festival holidays. It is true that workers get festival holidays—if the government announces Eid holidays to be three days, then the owners allow the workers to get 9, 10 or even 11 days. They are highly applauded for doing so too. What we do not see, however, is the price paid by the workers for this benefit. It is often seen that after coming back from this extended Eid holiday, workers have to do general duty on Fridays for weeks on end without any overtime payment.

But it is at the owner's behest that the workers get this extended holiday. If the workers wanted an extended Eid holiday, they could have used up their earned leaves. This arrangement simply benefits the owners monetarily, and otherwise. Workers can go home and rest for an extended period of time, but when they come back, they are subjected to inhumane work weeks. Workers become exhausted and ill, when toiling week after week without any days off. Their productivity and health suffer as well, ultimately affecting their life expectancy.

Nowadays, it can be seen that if two festival holidays fall on alternate days with a workday in between, workers are given three days off at a stretch, following which they are made to work on a Friday without overtime payment. We observe that in many areas, it has become common occurrence for workers to go to work on Fridays, treating it like any other workday. As a result, workers are deprived of many of the 52 weekly holidays they are entitled to.

The whole holiday system may seem to have been put in place for a humane cause, but within it hides a ruthless sense of selfishness. The health and leisure of the workers have nothing to do with this. It is simply a system to make sure that workers work longer, for cheaper, and are too tired to organise at the end of the week.

We used to see workers from different areas get different days of the week off. If the workers of Mirpur got Thursday off, then the ones in Badda would get Wednesday. As a result, they would not be able to meet and organise. This was a tactic used by owners to make sure that labour movements are restricted within neighbourhoods. But this did not stop them from meeting and organising. The current tactic, of getting workers to work on Fridays week after week, further hinders them from having enough time to organise.

When even the leave system can prove disadvantageous for the workers, then imagine how oppressive the other systems, like arrest and torture by the industrial police or violation of freedom of expression and labour rights, can be. While it seems that the owners are profiting temporarily, it is actually threatening the workers and their productivity—this can be seen in the pale, exhausted faces of the second generation of apparel workers. This never-ending toil, the wage discrepancy, the lack of any respite to think, to organise, all lead up to a decrease in productivity.

It is in the industry's interest to care about the wellbeing of the 44 lakh workers. We will all be benefitted. It is a known fact that workers will not be handed a reprieve from long work hours, or the leave trap. One hundred thirty-three years ago, it was the workers themselves who had to fight to ensure eight-hour workdays. Here, too, the labour movement must bring this issue to the forefront.

Taslima Akhter is President, Garment Sramik Sanghati, and a photographer.

The article was translated from Bangla by Zyma Islam.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments