How far can humanity go into the outer space?

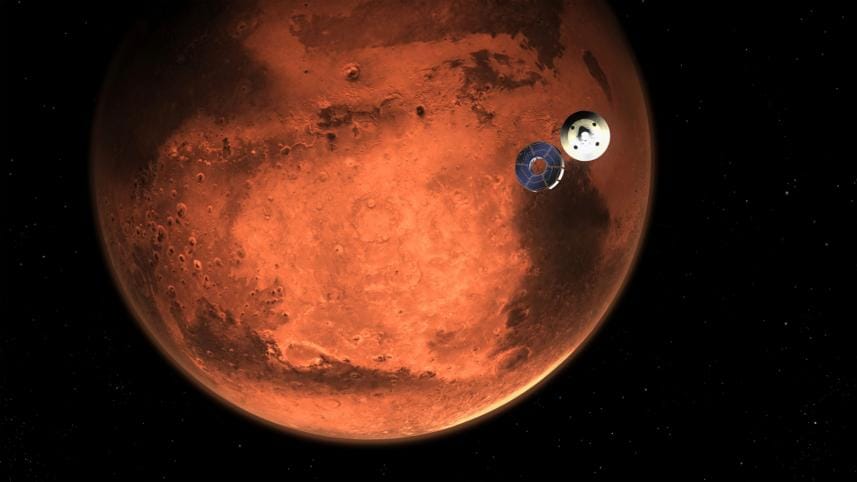

NASA has released a significant amount of footage, video feeds with audio, and reports on the operation of its Perseverance rover since its landing on Mars on February 18, 2021. From the slow and tense descent of Perseverance via its "sky crane" capsule towards its landing zone on Martian soil, to the panoramic view of the Martian landscape, the visuals coming out of this momentous event have been magnificent and literally "unworldly" to behold.

The landing video clip alone felt like something out of a sci-fi movie. This time, in addition to the photographs and video clips, NASA has introduced us to the sounds of Mars also. Listening to the recorded sounds of Martian winds blowing into Perseverance's microphone, as if you could hear the sounds of time passing in a different world, was a surreal experience.

Sadly, we are several decades away from exploring all the bodies—planets, planetary moons, asteroids, dwarf planets like Pluto, etc.—within our solar system with such depth as we have explored Mars. In fact, to explore all the heavenly bodies outside our solar system and galaxy might take us centuries in the future.

However, the in-depth exploration of Mars is something remarkable in this day and age. The fact that humanity can now operate complex machinery capable of sampling and investigating extra-terrestrial topsoil contents from a distance of more than 200 million kilometres away from our planet is nothing less than phenomenal.

Mars has been in the spotlight of humanity's first strides in interplanetary space exploration for over half a century, since the conditions on Mars are not as harsh as they are on other planets like Venus, where surface temperatures average at around 470 degrees Celsius, and also because the distance is financially and chronologically more viable than other planets in our solar system.

It should be kept in mind that if we can successfully manage to send and sustain human inhabitants on Mars, as well as utilise any of the natural resources to be found on the Red Planet, we can concentrate on inhabiting and/or utilising more heavenly bodies in outer space—within and outside our solar system.

Mars has had its first encounter with humanity through rovers back in 1971, under the Soviet Space Programme of the former USSR, according to an article by The Planetary Society in 1990. The Mars 2 rover was the first to land, and the Mars 3 rover followed suit a month later, in December 1971. But while the first crash-landed on Mars and was destroyed on impact, the second had a soft landing but "ceased transmissions 20 seconds after landing".

NASA, on the other hand, has had more success in landing and operating landers and rovers on Mars than any other space programmes of other nations or coalitions. According to old records, NASA managed to land its first spacecraft on the surface of Mars, named Viking 1 Lander, in the year 1976. Twenty-one years later, in 1997, it landed its first rover, Sojourner, successfully. Since then, NASA has managed to successfully land and operate four more rovers, namely Spirit and Opportunity (January 2004), Curiosity (August 2012) and Perseverance (February 2021).

There have been a number of other spacecraft landed by NASA like the 2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Science Laboratory, etc. along with orbiters like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

What is interesting, however, is that we may also be looking at a rejuvenation of the space race, this time the contenders being the USA's NASA and China's China National Space Administration (CNSA).

Ever since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, and perhaps even before that, NASA really did not have a fitting rival when it came to space exploration, as its strongest competitor, the Soviet Space Programme, had been significantly weakened. Gone are the days when Space Wars once heavily emphasised on whether an astronaut or a cosmonaut would set foot on the moon. The field for space race had long crossed the confines of Earth's orbit after the first moon landing in 1969.

With NASA landing its fifth Mars rover, CNSA is on its way to landing its first Mars rover, the Tianwen-1, in May 2021, according to the New Scientist magazine. The CNSA rover was launched in July 2020, and it has already entered the Martian orbit in February 2021. Tianwen-1is expected to land on Utopia Planitia, where NASA's Viking 2 lander spacecraft had landed in September 1976. This rover is China's first attempted interplanetary mission without international partners.

So we may be on the verge of witnessing another era of space race, a fierce and beneficiary competition between two superpowers. This time, there may be more than two strong contenders ready to be involved in this race, with the Indian Space Research Organisation and the still-strong Roscosmos of present-day Russia.

A space race should be a thing that we, the general people, should be looking forward to. This is because the race had previously introduced us to astounding innovations such as artificial limbs, scratch-resistance lenses, insulin pumps, firefighting equipment, and water filtration for daily use by ordinary people—innovations that we now take for granted. And a reignited space race in the Information Age can bring us so many new sights, knowledge, and technology, the importance of which we may not even fathom now.

So, could there have been even greater leaps in scientific advancement if CNSA and NASA worked together? Maybe. Yet, perhaps it is the sense of competitiveness in human nature that brings out some of the best innovations we have seen and perceived throughout history, and that trait can easily be carried over to the concept of space race. Though, we are yet to see whether Tianwen-1 will successfully land on Mars and be able to maintain communications with the CNSA command centre.

Nowadays, technology has advanced to such an extent that we have managed to get a detailed photographed image of the dwarf planet Pluto (5.2316 billion kilometres away from Earth), thanks to NASA's flyby spacecraft New Horizons. NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are now more than 22 billion and 18 billion kilometres away, respectively, from Earth, drifting further away at speeds of almost 17 kilometres per second (kps) and 15 kps, respectively, as tracked by NASA's Voyager Mission Status. And so many more interplanetary space exploration attempts have been made that it would be difficult for one person to keep track of all of them.

Who knows what we have in store for us in the future. Projects like the Artemis programme under NASA, for sending humans to Mars, and the development of the James Webb Space Telescope—under NASA, European Space Agency (ESA) and Canadian Space Agency (CSA)—for observing heavenly bodies at a much further distance, are already underway. Who knows how far humanity can go and achieve in the vastness of the outer space. Only time will tell. And Mars holds a crucial place in determining the fate of humanity's attempt in space exploration.

Araf Momen Aka is an intern at the Editorial department of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments