‘Neglect of workers mirrors the neglect of labour courts’

Razekuzzaman Ratan, assistant general secretary of Bangladesher Samajtantrik Dal (BSD), takes a deep dive into issues with labour courts in the country, in an exclusive interview with Naimul Alam Alvi of The Daily Star.

According to reports, more than 21,617 cases remain unresolved at labour courts in the country. About 75 percent of these cases have exceeded the designated timeframe for resolution, with some dragging on for as long as a decade. What factors contribute to this state of affairs?

Two major issues plague the labour court system in Bangladesh: the number and distribution of courts, and an inherent weakness in the legal framework.

Firstly, the current number of courts falls woefully short considering the needs of the vast workforce in the country. With 43 government-defined sectors relying on wage-board-determined pay and a labour force exceeding 73.6 million, the mere 10 labour courts nationwide simply cannot cope. Furthermore, their distribution is unbalanced, which leads to the neglect of many densely populated industrial regions. Imagine the plight of someone from Maona travelling all day to the Gazipur court or a Kishoreganj resident to Dhaka, just to file a case.

Secondly, an inherent flaw weakens the system's effectiveness. While regulations mandate case disposal within 90 working days, no penalty exists for exceeding this timeframe. This loophole incentivises various parties to delay judgments, further frustrating the already burdened system.

The court's composition comprises a chairperson (who holds decision-making authority) and two members (one representing owners and one workers). However, proceedings often get stalled due to the absence of all three members. Notably, owners' representatives are frequent absentees, while workers' representatives, predominantly affiliated with the ruling party's labour organisations, also exhibit inconsistent attendance. These absences further contribute to the case backlog.

While legal provisions regulate time extension petitions at the labour court, violations, unfortunately, persist. Conversely, rushed decisions sometimes lead to appeals, adding to the backlog.

The owners' financial advantage allows them to hire better lawyers, further limiting workers' access to legal representation. This struggle is exacerbated by the time-consuming nature of cases. A worker already facing wage deprivation gets financially crippled, with many running out of finances to run cases. For a worker earning a meagre Tk 12,500 per month, the potential legal fees and a lengthy wait for three months' unpaid wages can be insurmountable.

Is there any mechanism to hold the owners' representatives or labour organisation delegates accountable for their absence?

Theoretically, if someone cannot attend, they should inform the court beforehand, allowing the chairperson to adjust proceedings. Unfortunately, owners' representatives often fail to notify the court, and government-aligned labour representatives seem to also disregard this formality.

The expected protocol dictates that the court can then ask for a substitute in case of absence. However, this practice is rarely followed. While provisions exist to remove consistently absent members, these measures are not regularly implemented as far as I know.

What are the consequences of delaying cases?

Chronic delays at the labour court effectively deter workers from seeking justice, pushing them towards alternative, often disadvantageous solutions. They often settle for Alternative Dispute Resolution (system for discussion to resolve disputes), even when workers have to tackle industrial police or factory inspectors, further pressuring them to accept meagre settlements. The threat of years-long litigation, often emphasised by employers ("Take this now, or wait three-four years for your case"), instils fear and discourages pursuing legitimate claims.

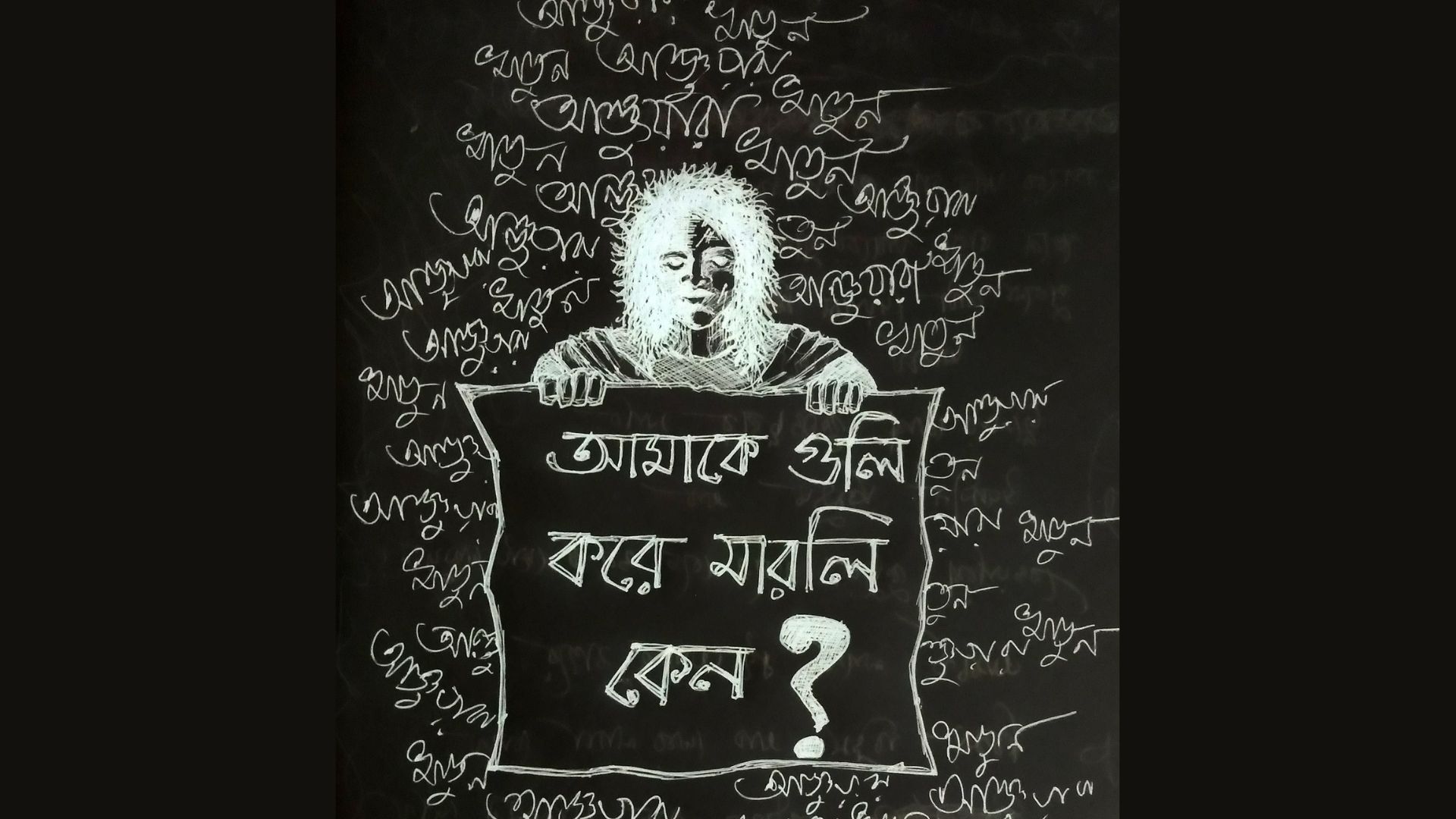

Consequently, the labour court, which is intended as a last resort for workers, fails to deliver due justice. This is why there are probably significantly fewer cases filed than there are actual disputes. This fuels worker dissatisfaction, fostering the belief that justice is unattainable, ultimately pushing them towards unrest and violence.

Why are the labour courts not active in disposing of cases?

Different labour organisations and activists are consistently highlighting some key weaknesses that hinder case disposal. One crucial factor is the sheer workload. We have seen chairpersons often juggling 30 to 35 cases daily. This makes it difficult for them to make timely resolutions.

Furthermore, there's a critical shortage of staff and resources in most of the labour courts. There are too few registrars, scribes, computer composers, and so on in comparison to the sheer number of workers they are supposed to cater to.

Further exacerbating the problem is a prevailing mentality that delays in labour courts are inconsequential and no one will be held accountable. Unlike other courts where exceeding timelines triggers disciplinary action for judges or members, labour courts face none of this. This fosters a culture of impunity, in which neither the chairpersons nor the members face consequences for delays or irregular attendance.

Essentially, the system lacks effective top-down monitoring. Even when grievances from below are being voiced persistently, no higher authority investigates the root causes behind the labour courts' dysfunction.

Do you feel that labour courts are being neglected?

In my view, the neglect faced by workers mirrors the neglect experienced by labour courts. As I said, one inherent problem is the lack of consequences for delays. The current system allows for judgments to be delayed without penalty.

Moreover, we see that more often than not senior district judges, many nearing retirement, are appointed as chairpersons in labour courts. They usually perceive this to be a decrease in professional status, and a step towards retirement. And so, they are less compelled to perform enthusiastically.

Astonishingly, the Ministry of Labour and Employment receives one of the smallest allocations in the country's annual budget. Considering the critical role it plays in the nation's production sector, where worker discontent simmers like a volcano, this meagre allocation raises serious concerns.

The inadequate funding manifests visibly in the labour courts themselves. Overcrowding, insufficient seating and poor maintenance are commonplace. Many courts operate in rented spaces, further constricting available space and creating chaotic conditions. The courts often lack even standing rooms for workers seeking justice.

If we ever go to the labour court, we will see the mismanagement all around. In many cases, we see chairpersons taking notes by hand themselves, because there are not enough stenographers or assistants. In many of the courts, there is no proper library, no proper place to keep the reference books. If the court members want to see the reference of any past case, then there is no opportunity for that. There's even no proper place to sit. The labour courts are more inefficient simply because of a lack of resources and workforce.

Besides, a deeply concerning mentality pervades the labour court system: normalising out-of-court settlements, often at the expense of workers' rights, by leveraging their fear of lengthy litigation. This "artificial solution" fosters a culture of intimidation, in which workers are pressured to accept meagre settlements rather than pursue their rightful dues through the court system. The prospect of waiting years for a resolution discourages many from filing cases in the first place. All these, in effect, help the owners to influence settlements in their favour.

Is the labour court effectively more accessible to the owner's side?

The power imbalance between owners and workers within the labour court system is undeniable. The owners' financial advantage allows them to hire better lawyers, further limiting workers' access to legal representation. This struggle is exacerbated by the time-consuming nature of cases. A worker already facing wage deprivation gets financially crippled, with many running out of finances to run cases. For a worker earning a meagre Tk 12,500 per month, the potential legal fees and a lengthy wait for three months' unpaid wages can be insurmountable.

Meanwhile, the senior and reputed lawyers, hired by owners, overpower the comparatively undistinguished lawyers, and even the chairpersons, who sometimes cannot hold their point against time extensions. This and the financial burden of prolonged litigation discourage many workers from pursuing their claims.

Is there anything that can be done to solve this issue of financing lawyers?

It's undeniable that in a capitalist country like ours, economic barriers to law will persist. It is a relief that you don't have to pay court fees for filing a case, but this is not enough to address the financial burden of legal aid.

One solution can be strengthening existing legal aid centres. Increased funding, staffing, and outreach could enable these centres to provide more comprehensive support to workers seeking legal representation in the labour court.

Additionally, leveraging the existing framework of trade union representation can be significantly beneficial. While individual union organisers may not have legal expertise, providing them with enhanced training and resources could empower them to effectively represent workers in court. This could be achieved through increased social support, capacity-building programmes, or even dedicated legal aid funds for trade unions.

Do you have other recommendations to make the labour courts more effective?

To enhance the effectiveness of labour courts, we propose three key recommendations. One, expand court coverage: increasing the number of labour courts will improve accessibility and reduce case backlogs. Two, enhance staff capacity: specialised training for labour court staff will expedite case processing and make writing judgments more efficient. And three, strengthen oversight and monitoring: implementing robust ministry supervision mechanisms must be ensured for timely case disposal.

Strengthening labour courts wouldn't just benefit millions of workers, but also fuel economic growth. With a thriving production sector heavily reliant on a satisfied workforce, bolstering labour courts can curb worker unrest and contribute to a more robust economy.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments